#OTD in 1906, a midnight shooting rocked Brownsville, TX ending in the wounding of police Lt. Joe Dominguez and the murder of bartender Frank Natus, eventually leading to Ranger Captain William McDonald to investigate the alleged involvement of Black soldiers from Fort Brown.

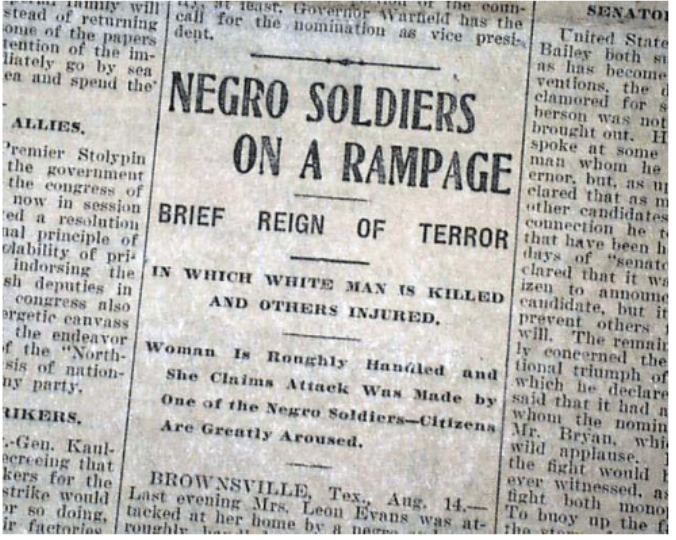

Capitan McDonald sealed his fame, and coined the current Texas Ranger motto, when at the Fitzsimmons Maher prizefight in 1896, he answered a confused officer on why he was the only Ranger – “One riot, one Ranger.”

The morning of Aug. 14, men of Brownsville formed a citizen’s council to investigate, and immediately accused the Black soldiers of the crime. Armed men surrounded the fort, demanding Major Penrose turn over the troops to them.

The vigilantes appealed to TX Governor Samuel Lanham, who eventually sent Texas Ranger Captain William McDonald to take over. McDonald secured bench warrants from Judge Stanley Welch, and immediately demanded that Penrose release the prisoners to his custody. Penrose refused.

Penrose feared that the gathered mob would lynch the soldiers if handed over. He had every right to be worried. By the time of the Brownsville Affair, white Texans had engaged in at least 50 lynchings of Black men and boys.

http://www.lynchingintexas.org/items/browse?search=1905&sort_field=relevance

Angered by Penrose’s refusal, Capt. McDonald took to the press to assure the white people of Texas that he did everything in his power to arrest the soldiers. He had the papers print correspondence he sent to the governor, Army officials, and even President Theodore Roosevelt.

As the pressure mounted, and the fear of mob violence strengthened, Judge Welch thought it better that he revoke the warrants and ask Capt. McDonald to leave Brownsville. Many citizens believed his presence made the situation worse.

McDonald, however, insisted that he “would make the arrests at any cost,” including stopping a train commissioned to take the Black soldiers to Fort Reno in Oklahoma. Doug Swanson in Cult of Glory writes that McDonald actually hurt his image, even the Brownsville press accused McDonald of trying to stir up trouble for his own glory.

Yet McDonald messaged Gov. Lanham, fearful that Penrose was “protecting the guilty.” In fact, McDonald wanted to have the soldiers indicted first and then collect the evidence to convict them, already convinced of their guilt.

Penrose received orders to take the soldiers to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio to await investigation for fear of vigilante violence in Brownsville.

The Brownsville Herald published a common trope that the white men just wanted to “protect from the unspeakable crime against their neighbor women and other Negroes threatening to pillage and murder,” preemptively excusing a possible lynching.

The article then explained that the soldiers had it coming because the day before a group of Black soldiers brushed up against a white woman and then were attacked by white men.

Judge Welch organized a grand jury to investigate the matter, as well as look over the 3 affidavits McDonald presented to the governor. In a few weeks, the grand jury dismissed the charges against the soldiers for lack of evidence and no testimony from McDonald.

McDonald erupted at the lack of indictments and vowed to take the case further than the state. He said his absence was due to an illness. Then he reached out to state senators and to President Roosevelt.

Roosevelt looked favorably on Capt. McDonald, even writing him a letter that appeared in McDonald’s memoir in 1909 remembering the time McDonald served as his bodyguard in 1905. Roosevelt demanded that the soldiers confess or “leave the Army.”

No soldiers confessed or admitted that any soldier perpetrated the crime. Several publications floated the idea that white citizens dressed as Black soldiers with stolen uniforms. But the Brownsville citizen council and, more importantly, US Senators from Texas called this preposterous.

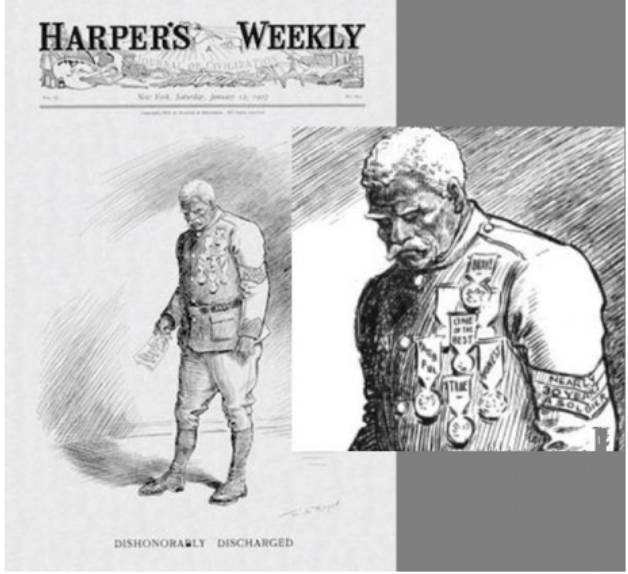

In early November, Roosevelt dishonorably discharged 167 Black soldiers. His actions led to national outcry and a federal investigation, where Republican Ohio Senator Joseph Foraker accused Roosevelt of overstepping his authority.

Foraker even called out Capt. McDonald, who by this time had retired from the Rangers to become a state revenue agent. The national fight over the Brownville Affair turned into a boxing match of public insults.

The @txrangermuseum makes no mention that the description of McDonald as a “man who’d charge hell with a bucket of water” Foraker also used to point out his lack of self restraint.

https://www.texasranger.org/texas-ranger-museum/hall-of-fame/william-jesse-mcdonald/

Foraker challenged McDonald to come to DC.. McDonald shot back that “he’d go forty miles out of his way to be cross questioned by the defender of the n—–.” Foraker became known in the Texas press as a negrophile for insisting that the soldiers be reinstated.

McDonald was heroized in the press. The El Paso Herald noted that “Capt. McDonald is the most noted peace officer in the southwest… he has killed a number of men in the performance of his duty.”

The fervor over the matter died down in the first months of 1907. But Foraker and Morgan Bulkely (R- Connecticut) continued the fight to clear the soldiers. In 1910, the Court of Military Inquiry reviewed the applications for reenlistment of the soldiers, approving only 14.

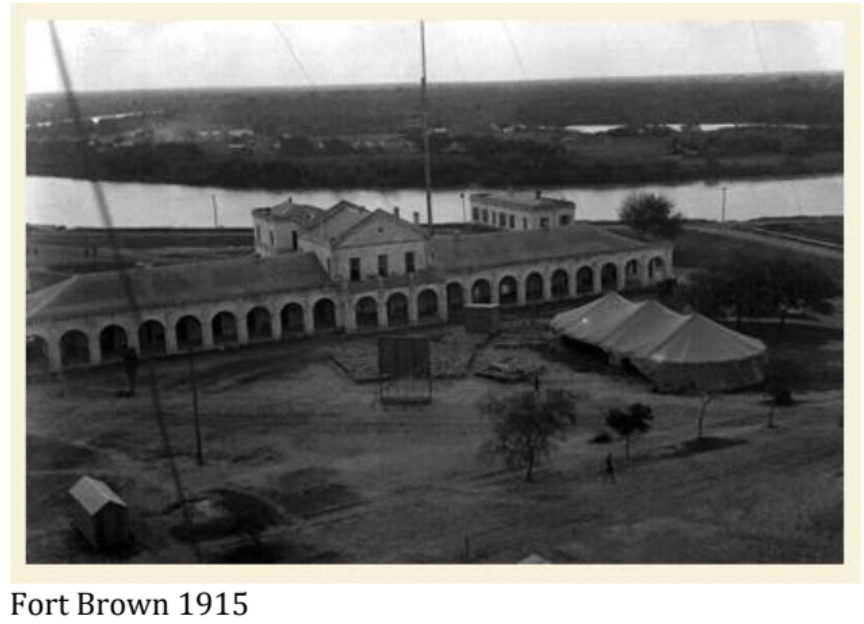

The matter left public prominence as Foraker was not renominated, Penrose was cleared by a court martial, Judge Welch was assassinated, and the military closed down Fort Brown and turned it into an experimental garden for spineless cacti. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/fort-brown

By the start of World War 2, the military turned the fort into a district headquarters and then the headquarters for the Twelfth Calvary. https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/american_latino_heritage/fort_brown.html

Capt. McDonald died of pneumonia in 1918, but the “Brownsville Affair” continued to rankle civil rights leaders.

An investigation in the 1940s prompted by Congressman August Hawkins, a Black Democrat from California, concluded that “the military shell casings from the scene were not fired in Brownsville.” McDonald was wrong.

Decades later, prompted by Lt. Col. William Baker, President Richard Nixon declared the soldiers honorably discharged, but provided no back pay. Continued pressure resulted in a pension being awarded to Dorsie Willis, the last surviving solider.