September 10, 1956: J.E. Banks Supports a White Segregationist Mob

On this day in 1956 Ranger J.E. Banks arrived in Texarkana, TX, to “keep the peace” as two Black students attempted to integrate Texarkana Junior College. As in Mansfield, Banks supported the white segregationist mob.

Learn more about Banks’ failure to uphold the law just days earlier during the attempted integration of public schools in Mansfield, TX, here.

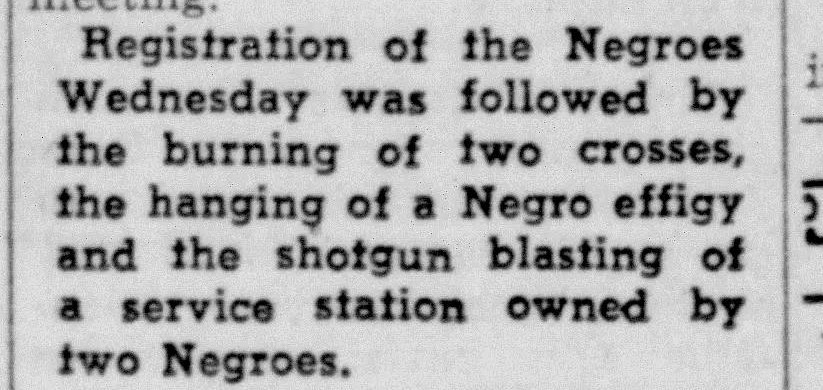

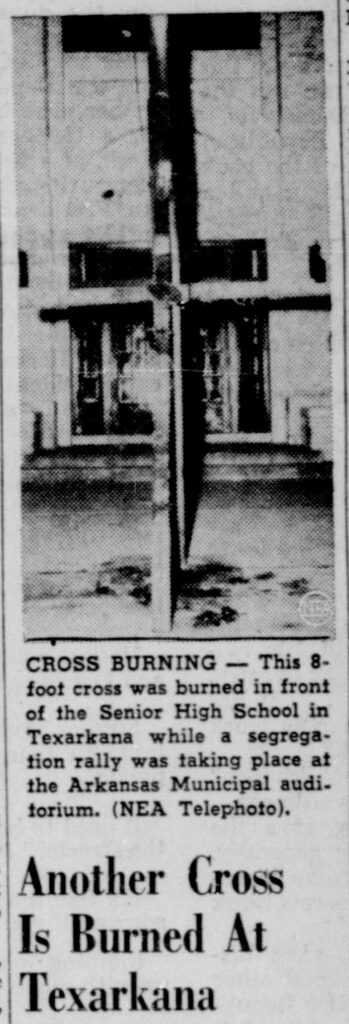

Texarkana was publicly funded and subject to desegregation under Brown v Board (1954), but after Black students registered, crosses were burned, a Black person was hung in effigy, and shots were fired into a Black-owned gas station and near a Black church. The Junior College President H.W. Stillwell also firmly supported segregation. On Sep. 6 he “told a cheering White Citizens Council meeting…that ‘it is not only your right, but your duty to resist [integration]’” because it would lower educational standards.

![Clipping of a newspaper column reading, “Another cross was burned, this tim [sic] in front of the Texarkana, Tex., high school, Thursday night. In Addition police had several reports of shotguns being fired in the vicinity of a Negro church Thursday night while choire [sic] practice was going on.”](https://refusingtoforget.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Brownwood-Bulletin-Sep-7-1956-p-1_cropped2.jpeg)

Banks met with the president of the White Citizens Council, J.F. Williamson sometime before Sep 10. He recalled, “I told him exactly what his group could do without crossing us… We got along fine. We were soon good friends.”

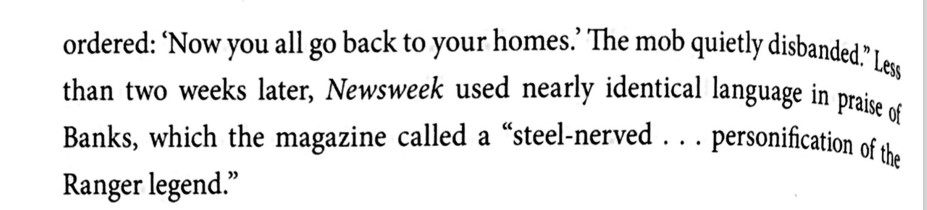

On Sep 10, Jessalyn Gray (18) and Steve Posten (14) arrived at the Junior College in a cab. Gray had passed the admissions exam, and Posten was returning to see if he had passed. They faced a large, angry white mob. Two reporters tried to interview Gray and Posten, but Banks threatened them with arrest and forced them away. While he was busy, mob members jeered at Gray and Porten, threw gravel at them, and kicked Posten. Gray and Posten left.

Gray returned about 45 minutes later and tried again to enter the school. This time, she asked Banks for protection from the mob. Banks refused. He explained afterwards, “We were under no obligation to escort any person in or out of the school.” That was Banks’ interpretation of his job: “keep order” at the expense of Gray and Posten’s civil rights, even threatening Gray with arrest. Banks used civic order and his responsibilities as a member of law enforcement is avoid upholding the law.

![Black-and-white image of Gray, a Black teenager, talking with Banks, a middle-aged white man. Two white men stand around Banks looking at Gray. Behind them is a sign reading, “[N-words] stay out!!”](https://refusingtoforget.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/RangerMaybeBanks-771x1024.png)

Gray left for her own safety and later enrolled at North Texas State College (now the University of North Texas). She died in 2018.

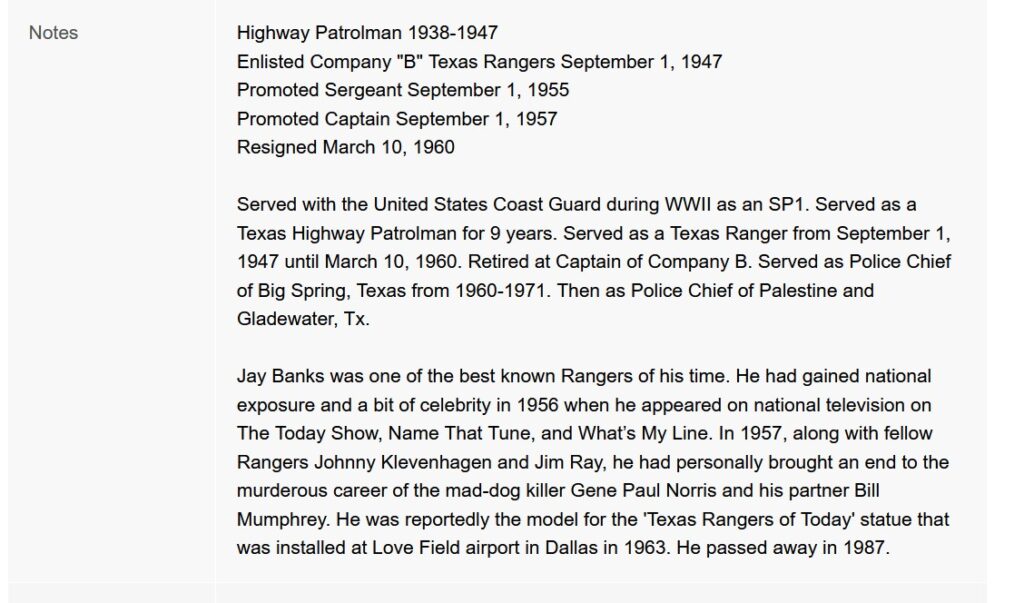

Life magazine photojournalist Joe Scherschel took pictures of the mob, some of which are in this thread. He later said, “These kids were literally run off by the mob… There were at least three Texas Rangers in the crowd, and not one of them lifted a finger.” The White Citizen’s Council appreciated the Rangers’ work. President Williamson said they had thwarted the goals of the “Communist NAACP,” and Banks said, “we all parted friends.” Banks was promoted to captain soon after.

![Black-and-white photo of a group of white people, mostly men, milling about on a sidewalk and field. Some hold signs. The only readable one says, “Go Home [N-word].”](https://refusingtoforget.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/GoHomeNWord-1024x659.png)

This approving tone transformed tellings of Banks’ actions in Mansfield and Texarkana. Newspapers reported that the Rangers had helped prevent violence and “[break] up anti-integration crowds”—leaving out that they did so by upholding segregation.

As of August 2023, Banks’ support for violent, racist mobs in Mansfield and Texarkana is not included in his Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum biography. According to the museum, his only important actions in 1956 were fun appearances on national TV.

You can learn more about Texarkana’s history of segregation in the online exhibit Equal But Separated by Katherine Anne Doan. Many images in this thread come from this project. Doug Swanson also covers the desegregation attempt in his book Cult of Glory: The Bold and Brutal History of the Texas Rangers, a main source for this thread. See pg. 326-366.