#OTD in 1956 Texas Rangers under J.E. Banks arrived in Mansfield, TX, to help “keep the peace” during the failed attempt to desegregate Mansfield High School. They supported white segregationist mob.

CW: discussions of lynching, racist slurs, use of the n-word

The 5th US Circuit Court of Appeals had ordered Mansfield to desegregate its high school earlier that August, based on lawsuits filed after Brown v Board declared segregated schools unconstitutional. This was the first time a federal court ordered a Texas school to desegregate, and white residents of Mansfield were enraged. A mob blocked the high school, and an effigy of a Black person was hung on Main Street w/ the sign “This would be a horrible way to die.”

There were other clear threats of racist violence. The Amarillo Daily News reported that a member of the mob threatened to use guns against students who tried to desegregate the school and threatened to bomb the house of a relative of one of the Black students.

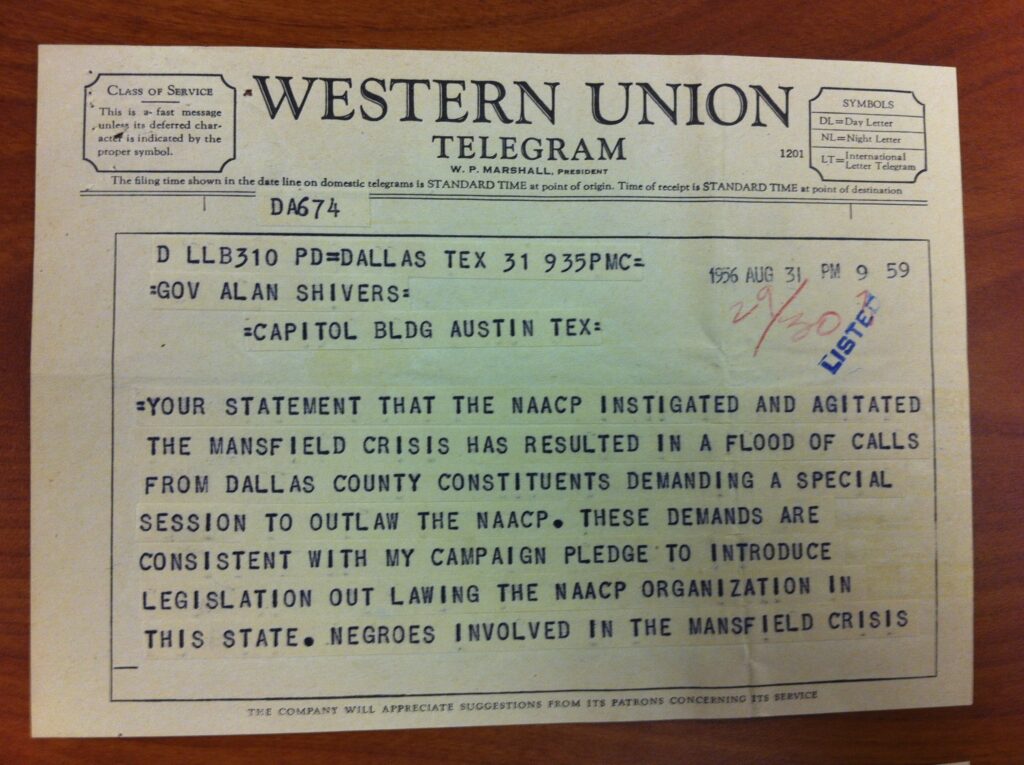

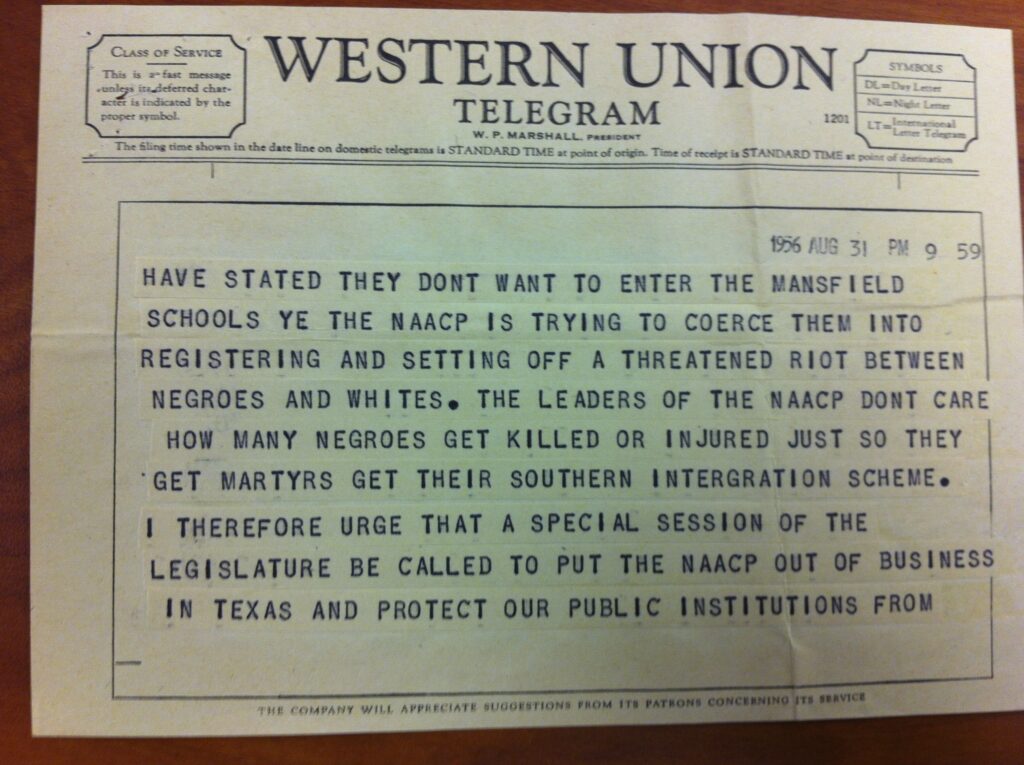

Gov Allen Shivers refused to uphold the court order. He ordered Rangers to Mansfield but directed them to arrest any Black students who tried to enter the high school. Any Black students who enrolled would be immediately transferred out of the district. Shivers said he refused to use law enforcement “to shoot down or intimidate Texas citizens who are making an orderly protest against a situation instigated and agitated by the [NAACP].”

![Black-and-white photo of white men and boys gathered around a white man holding a baby alligator. The people in the crowd hold signs reading “we want segregation” and “we don’t want no [n-word].”](https://refusingtoforget.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/CrowdSigns-1024x825.jpg)

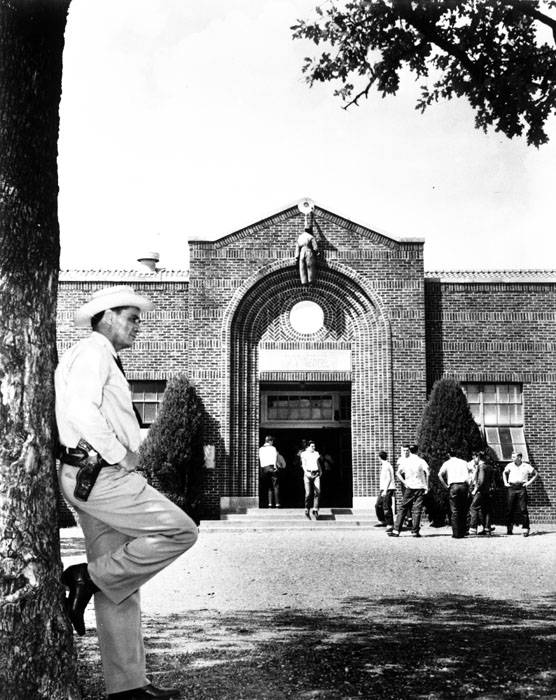

Banks agreed. He said the mob “were just salt-of-the earth citizens who had been stirred up by agitators. They were concerned because they were convinced that someone was trying to interfere with their way of life.” Meanwhile two more effigies appeared on the high school itself. Willie Pigg, the principal, refused to cut them down because he hadn’t put them up.

Banks also made no attempt to remove them, resulting in a photograph that defined the situation: a white officer lounging against a tree—and ignoring both explicit, actionable threats of racist violence and his legal duty.

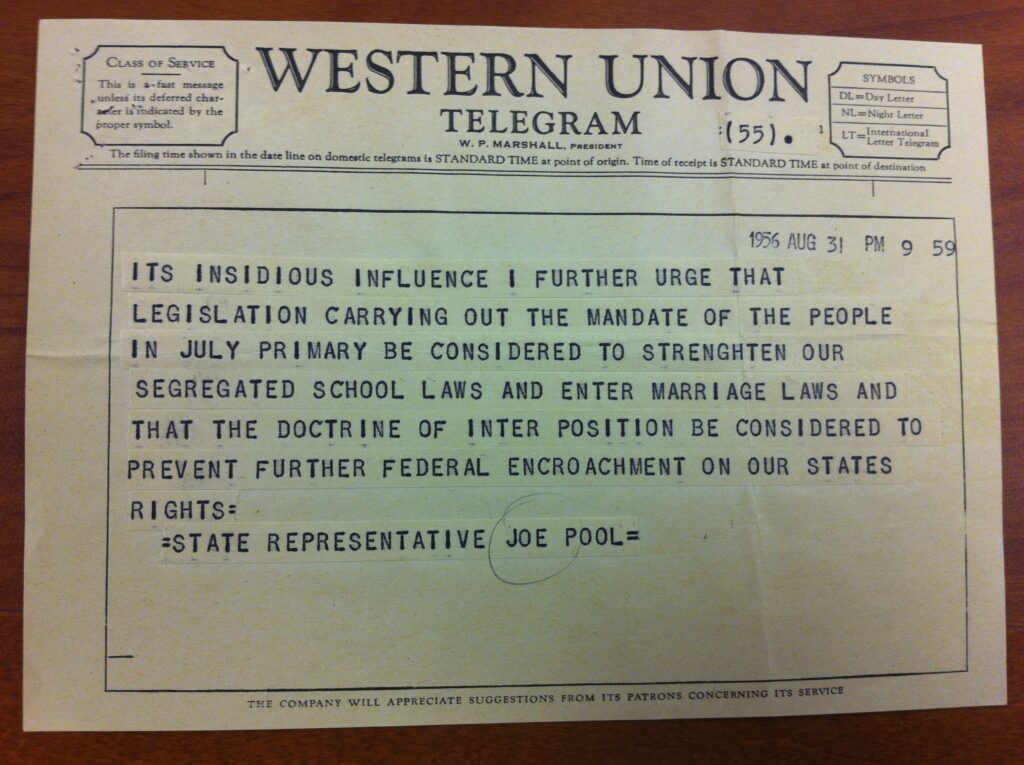

When it became clear that law enforcement would not protect them, the Black students who planned to enroll decided not to. These students included Gracie Smith, Hattie Neal, Floyd Moody, John Hicks, and Charles Moody. Floyd Mood recalled the experience in this article. The NAACP suspended its efforts a few days later to protect the Black students. Mansfield’s schools remained illegally segregated until after the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

White leaders and residents thought the solution to school desegregation riots like those at Mansfield was to outlaw the NAACP in TX. This interpretation cast the NAACP as outside agitators forcing happy Black Texans to misbehave. This is the same narrative Banks used when he said the white rioters had “been stirred up by agitators.”

In fact, Banks’ greatest interventions in the pro-segregation demonstrations were removing so-called agitators: a man distributing “inflammatory literature”—IE pro-integration literature—and an Episcopal priest preaching love for one’s neighbor.

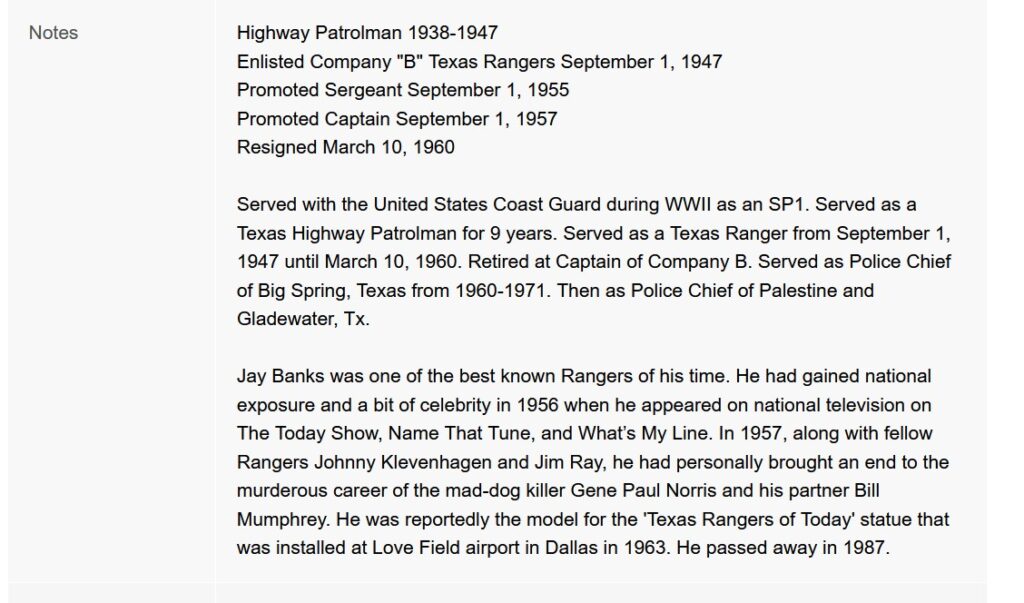

As of August 2023, Banks’ support for a violent, racist mob does make it into his @txrangermuseum bio. According to the museum, his only important actions in 1956 were fun appearances on national TV.

Moreover, in November 2022, Russell Molina, chair of the Ranger Bicentennial (texasranger2023.org/cof/) defended Banks’ actions.

See 26:15 of this recording: Texas Ranger Summit 2022: Part 4

Learn more about the crisis in Mansfield in this online exhibit by graduate and undergraduate students at the University of North Texas. Some images in this thread come from this exhibit. Doug Swanson also covers the desegregation attempt in his book Cult of Glory: The Bold and Brutal History of the Texas Rangers, a main source for this thread. See pg. 326-366.

This brief thread by @Ryan_Abt captures the vitriolic racism directed at the Black students and offers observations about the next decade at Mansfield: https://twitter.com/Ryan_Abt/status/1436409702192193542?s=20

In 2020 Texas removed a statue of a Ranger from Love Field because of the Rangers’ brutal history. One specific reason was that the statue was likely modeled on Banks.

The Horrible Truth of Love Field’s Texas Ranger Statue – D Magazine

For more on the brutal and complicated history of the Texas Rangers, follow @Refusing2Forget or explore this blog.