#OTD under the direction of Leander Harvey McNelly, a group of Texas Rangers attacked Mexican men moving cattle ten miles north of the Rio Grande who were supposedly herding cattle stolen from white ranchers.

12 of the Mexican men were killed, of somewhere between 12 and 14 total, and their bodies were publicly displayed in Brownsville, Texas as a warning. A firsthand recounting of the events by N.A. Jennings describes one Ranger being shot and killed in the chase.

According to a notice from the Office of the Inspector of Hides and Animals a few days after the event, 216 cattle were claimed in the attack and many of them did bear Texas brands.

But no matter the number of cattle rightfully retrieved, Margarito Vetencourt, a friend of one of the dead, claimed that the 12 men “had been unjustly killed and fouly murdered… by the State troops.”

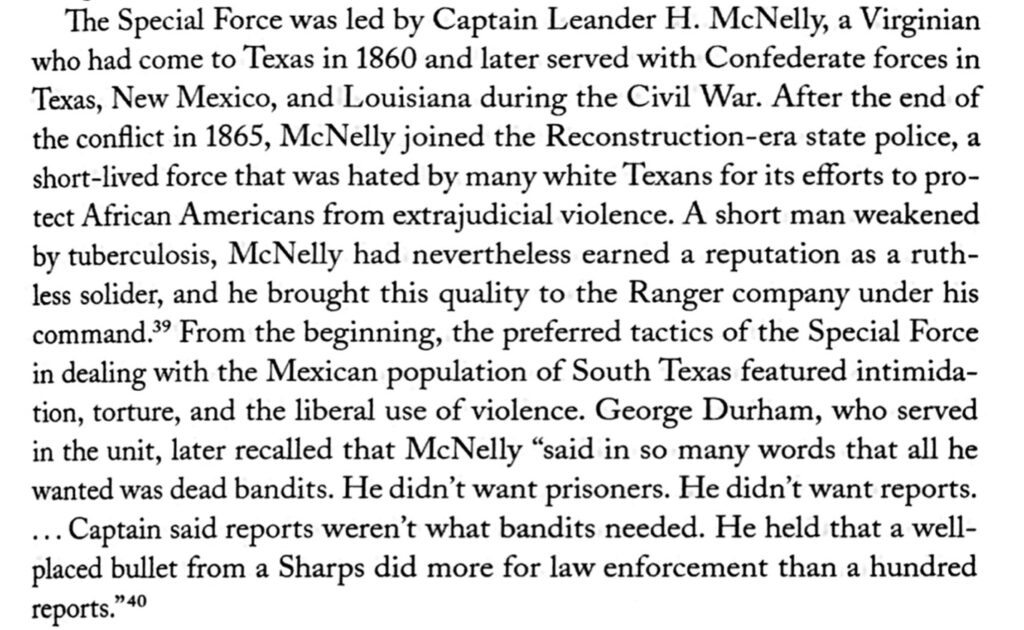

Graybill also cited another member of McNelly’s force who claimed that McNelly “said in so many words that all he wanted was bandits. He didn’t want prisoners. He didn’t want reports.”

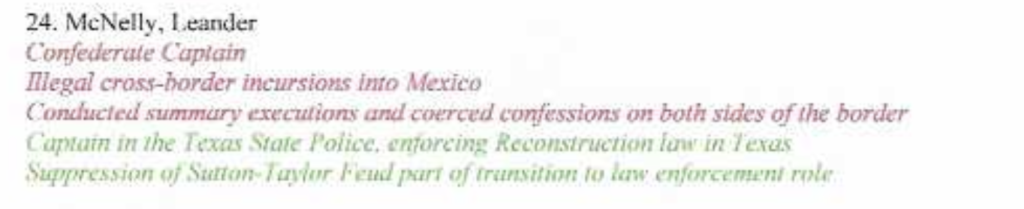

McNelly was infamous for his ruthless tactics. According to the @txrangermuseum, he had been given leadership of a “special force” within the Texas Rangers who were tasked with protecting the frontier.

Image and Text from:

https://www.texasranger.org/texas-ranger-museum/hall-of-fame/leander-harvey-mcnelly/

McNelly’s Hall of Fame entry notes that while the “special force” was effective, “many saw their tactics as too aggressive.” It notes McNelly’s habit of crossing the border into Mexico, which was illegal, to recover stolen livestock.

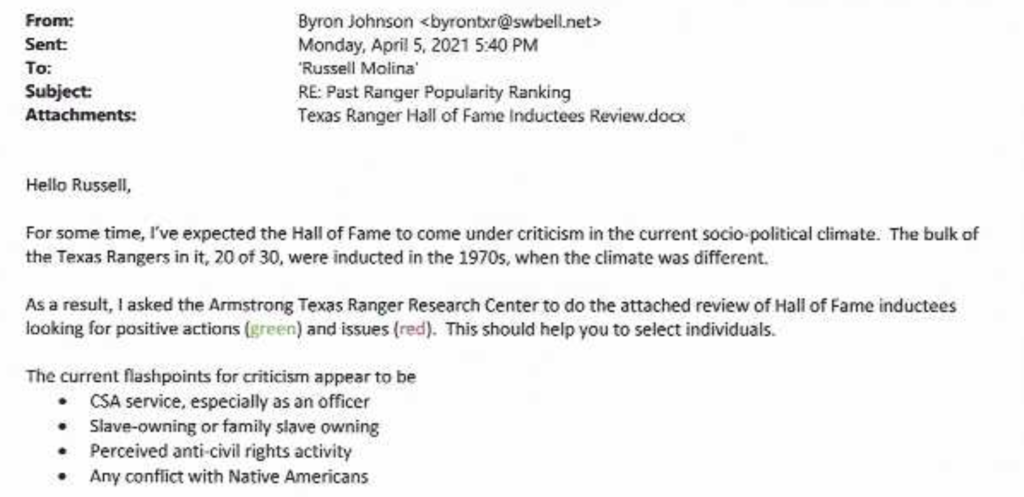

In correspondence between with Ranger 2023 head Russell Molina, Texas Ranger Museum director Byron Johnson is even more direct in acknowledging McNelly’s illegal violence, though they don’t broach the idea of removing him from the Hall of Fame.

McNelly would go on to participate in the violent murder of more Mexican men across the Nueces Strip, seemingly unperturbed by any disapproval. For without any real consequence for these killings, he was free to continue on as he wished.

Graybill argues McNelly’s violent impulses and authorization of racial violence, especially towards ethnic Mexicans, emerged from remaining anti-Mexican sentiment after the Mexican-American war in Texas.

(Andrew Graybill: Anglos, Mexicans, and Rangers in Texas, 1850-1900. Pg. 56-7)

Graybill also suggests that this regular violence in South Texas in the late nineteenth century maintained the antagonistic conditions that would result in the notoriously brutal violence of the 1910s across the border. (Graybill 56)

McNelly’s need to explicitly direct his men to kill, instead of capture, supposed Mexican livestock thieves demonstrates that their murders were not considered necessary or even widely demanded at the time. https://archive.org/details/texasranger00jenn/page/140/mode/2up

These murders and the brutal treatment of the victim’s’ bodies were, on the other hand, authorized by the state through McNelly in his role as a Ranger captain.

This thread is a part of the #OTD in Ranger history campaign that @Refusing2Forget is running this year. Follow this twitter handle or https://refusingtoforget.org/ranger-bicentennial-project/, and visit our website https://refusingtoforget.org to learn more.

Refusing to Forget members are @ccarmonawriter @carmona2208 @acerift @soniahistoria @BenjaminHJohns1 @LeahLochoa @MonicaMnzMtz and @Alacranita, another co-founder is @GonzalesT956

.@emmpask @sdcroll @HistoryBrian @LorienTinuviel @hangryhistorian, @ddsanchez432, @elprofeml, and @littlejohnjeff are other scholars working on this project.