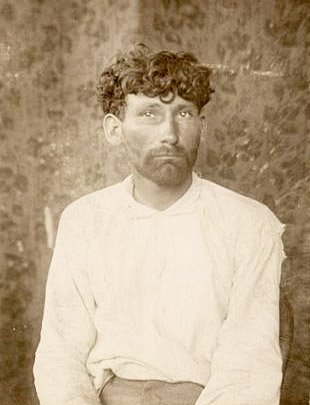

#OTD on June 12, 1901 Gregorio Cortéz killed 2 Texas law officers in self-defense and led Texas Rangers on a nearly 10 day chase through south central Texas. Cortez was regarded as a “bandit” by the law but became a hero to many Mexican Americans.

Cortéz was born in Mexico and moved to Texas in 1887. In the 1890s he ran a small rancho with his family. On June 14, 1901, Karnes County Sheriff William Morris went to Cortéz’s farm to question him about a horse theft. Poor translation from Deputy Boone Choate led to gunfire.

Choate asked Cortéz if he had sold a horse. Cortéz replied “no” and explained he had sold a mare. Choate did not understand and told the sheriff he was lying. Morris then attempted arrest Cortéz. Romaldo Cortéz, Gregorio’s brother, attempted to intervene.

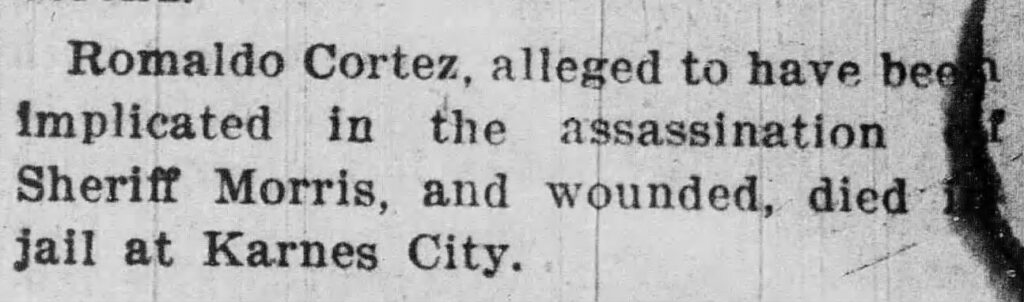

Morris shot Romaldo and shot at Cortéz. Gregorio returned fire, critically wounding Morris. The other deputies fled. Morris died a short time later at the scene. Romaldo survived for about a month, but died in jail from his injuries.

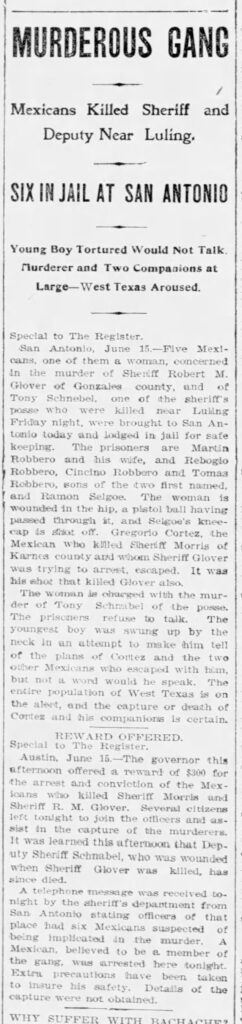

Cortéz fled to his friend Martin Robledo’s house. A sheriff’s posse tracked him there and shot up the home. Cortéz fled again, killing Sheriff Robert Glover in a shootout. A posse member, Henry Schnabel, died in a friendly fire incident. Cortéz was blamed for his death too.

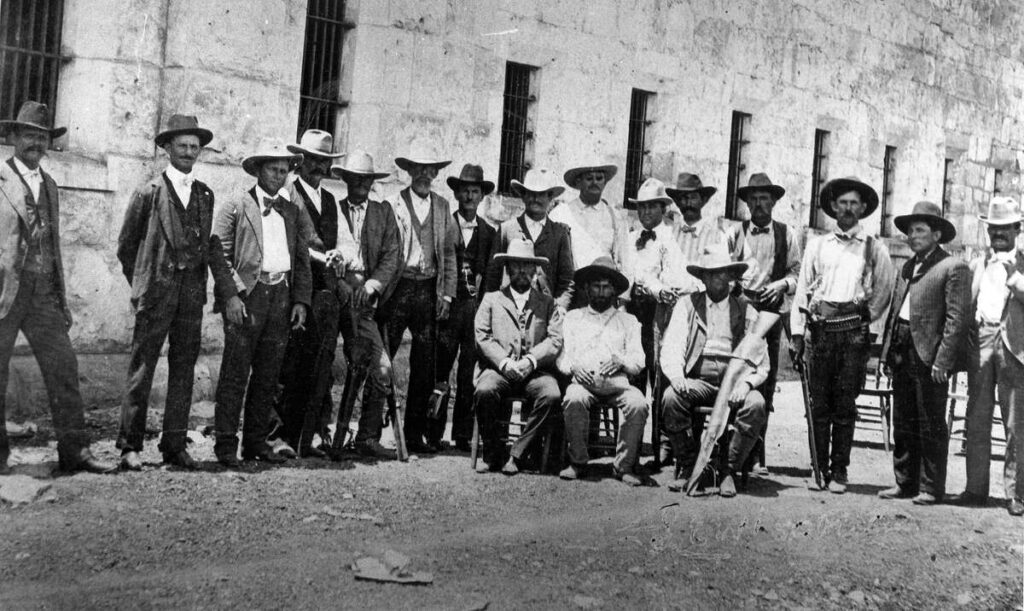

The multiple deaths prompted involvement from the Texas Rangers. Captain John Rogers took charge of the now 300 person posse. Cortéz eluded this posse for over a week, riding over 400 miles. Rogers finally tracked Cortéz to a ranch and took him into custody without incident.

The Rangers took Cortéz to jail in San Antonio to avoid lynch mobs that had formed near Karnes County. Mexican-origin people launched a legal defense effort to try to ensure that he received a fair trial. That network secured financial and political support for Cortéz.

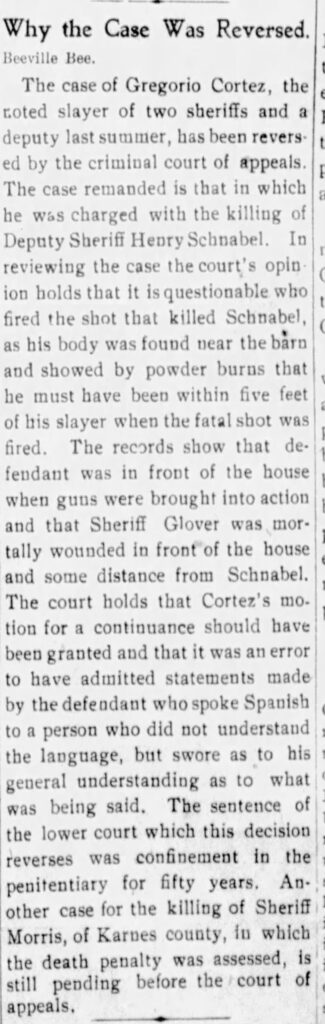

Cortéz was first tried for the killing of posse member Henry Schnabel. The jury convicted Cortéz of second degree murder and sentenced him to a 50 year prison term. That case was later reversed because Cortéz did not kill Schnabel, rather a fellow posse member did.

The state also tried and convicted Cortéz for horse theft, the original reason Sheriff Morris had gone to his home. Upon appeal, the court determined that he owned the mare he had sold, so he had committed no crime. The appeals court overturned his conviction for horse theft.

The state also tried Cortéz for the death of Sheriff Glover, which resulted in another conviction and a life sentence. This conviction would be the only one to stand, even though Cortéz had again acted in self-defense when he shot Glover.

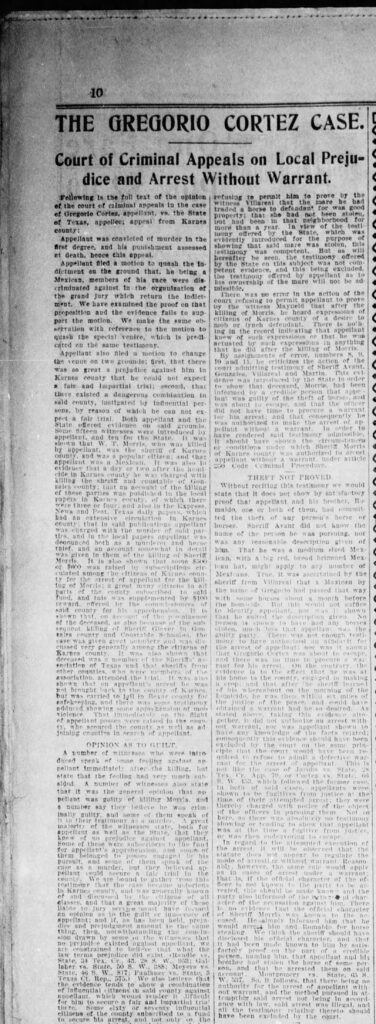

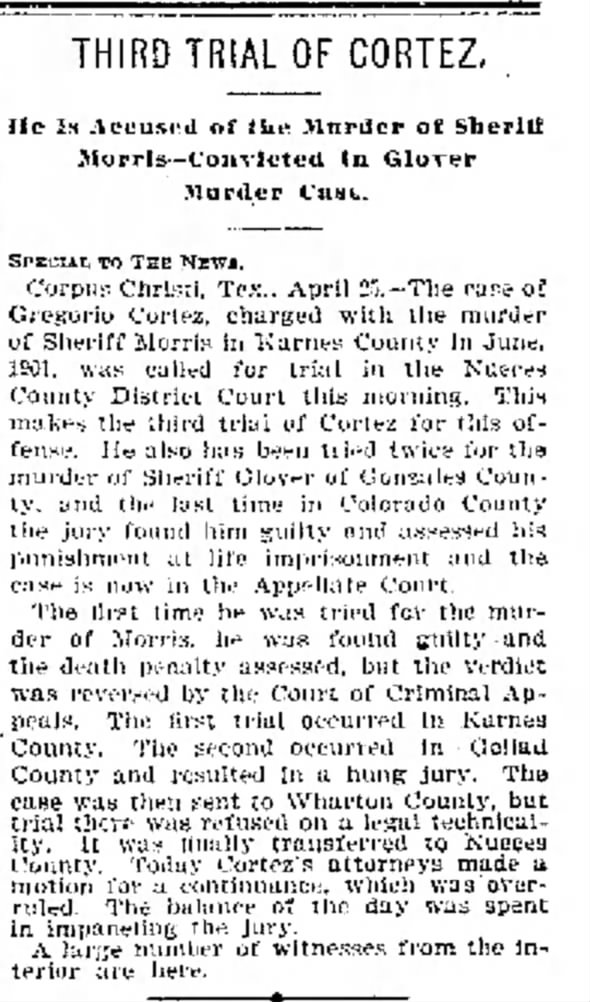

The trials for the death of Sheriff Morris were complex. The first resulted in a conviction and death sentence. Upon appeal, the court found a number of irregularities especially the warrantless attempted arrest of Cortéz. The court overturned this conviction in June 1902.

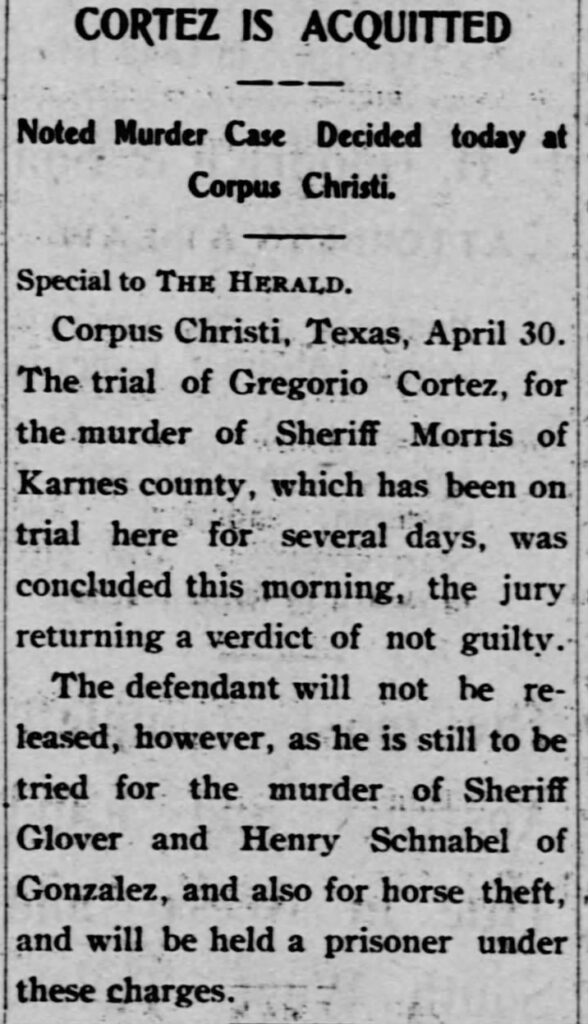

The state tried again, but that trial resulted in a hung jury. Another trial took place in 1904. That trial, presided over by Rio Grande City District Court Judge Stanley Welch in Corpus Christi, proceeded to a conclusion.

The jury heard evidence about the poor translations offered by Deputy Sheriff Choate and deduced that Cortéz had acted in self-defense. The all-male, all White jury found him not guilty of murdering Sheriff Morris, a conclusion that for the time was exceedingly unusual.

Cortéz began serving his life sentence for death of Sheriff Glover in 1904. The Cortez defense committee continued its work and ultimately secured a pardon for him in 1913 from Governor Oscar Colquitt. He was released from prison but died of an undisclosed illness in 1916.

Gregorio Cortéz was not a bandit. He did not steal horses nor sell stolen horses. When Morris attempted to arrest Cortéz for a crime he did not commit, Cortéz shot Morris in self-defense only after the sheriff had shot Romaldo and after Morris had attempted to shoot him.

That Cortéz fled seems hardly surprising given the fate that awaited Mexican people who killed White law officers. At Martin Robledo’s house posse member Schnabel and Sheriff Glover both died. But Cortéz did not kill Schnabel and he acted in self-defense when he killed Glover.

The Rangers mounted a huge posse. Ranger Rogers should receive credit for arresting Cortéz without incident. The Rangers also protected him when lynch mobs formed to murder him. Alas, mobs killed an unknown number of Mexican people during the hunt for Cortéz.

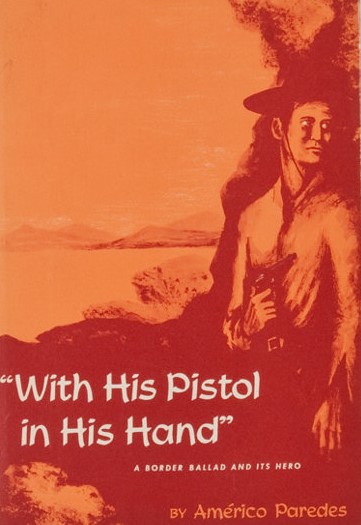

The legend of Cortéz’s flight from the Rangers became a touchstone of Mexican American Studies, especially because of Américo Paredes’ hugely influential 1958 book, a major source for this thread. https://refusingtoforget.org/publication-of-paredes-with-his-pistol-in-his-hand/

Another key source for this thread is @HistoryBrian’s Borders of Violence and Justice.

This thread is a part of the #OTD in Ranger history campaign that @Refusing2Forget is running this year. Follow this twitter handle or https://refusingtoforget.org/ranger-bicentennial-project/, and visit our website https://refusingtoforget.org to learn more.

Refusing to Forget members are @ccarmonawriter @carmona2208 @acerift @soniahistoria @BenjaminHJohns1 @LeahLochoa @MonicaMnzMtz and @Alacranita, another co-founder is @GonzalesT956

@emmpask @sdcroll @HistoryBrian @LorienTinuviel @hangryhistorian, @ddsanchez432, @elprofeml, and @littlejohnjeff are other scholars working on this project.