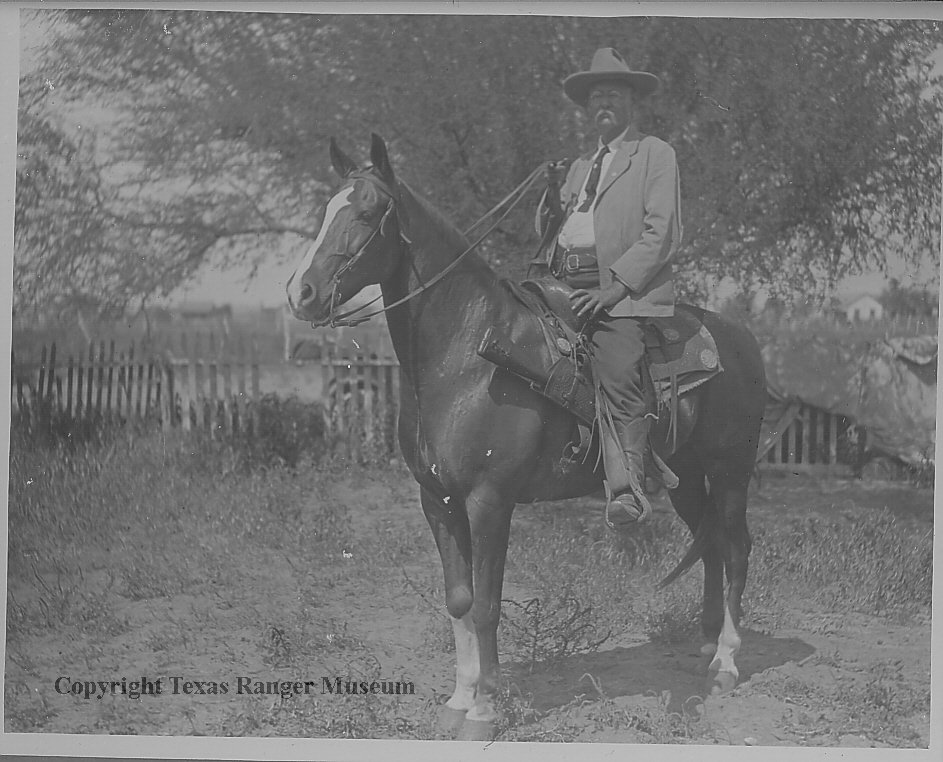

On this day in 1916, José Morin and Victoriano Ponce disappeared while in the custody of Ranger Captain J.J. Sanders. The men were suspected of attacks against U.S. citizens, but neither had been tried for the crimes or even formally accused of anything.

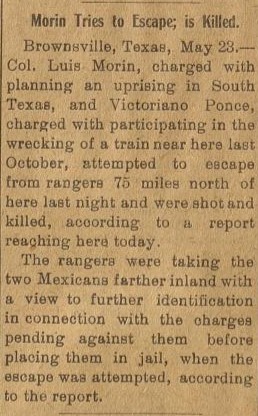

Newspapers later reported that the men were shot while trying to escape Ranger custody. While that is possible, it is important to remember that ‘shot while escaping’ was a common Ranger excuse for executing prisoners, especially ethnic Mexicans, in cold blood.

Contemporaries recognized that Rangers used ‘shot while escaping’ as an excuse to murder captives, as this editorial in The Daily Bulletin of Brownwood, Texas, shows. But despite acknowledging the violence and illegality of such killings, this (presumably white) author was more concerned with the way they might stain the Rangers’ honor than the threat they posed to the Rangers’ prisoners. The author condemns the “law of the fugitive,” in which a prisoner is encouraged to escape, only to be shot for doing so. They write, “There is a suggestion that Louis Morin and Victoriano Ponce, the two alleged Mexican bandits who were shot by the Texas Rangers ‘while attempting to escape’ were victim of the ‘law of the fugitive.’ Let us hope, for the honor of the Texas Ranger Service, that the suggestion is groundless.”

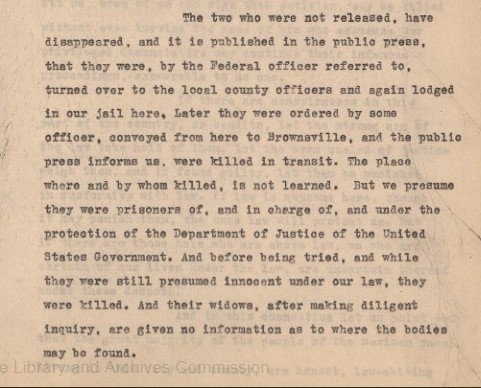

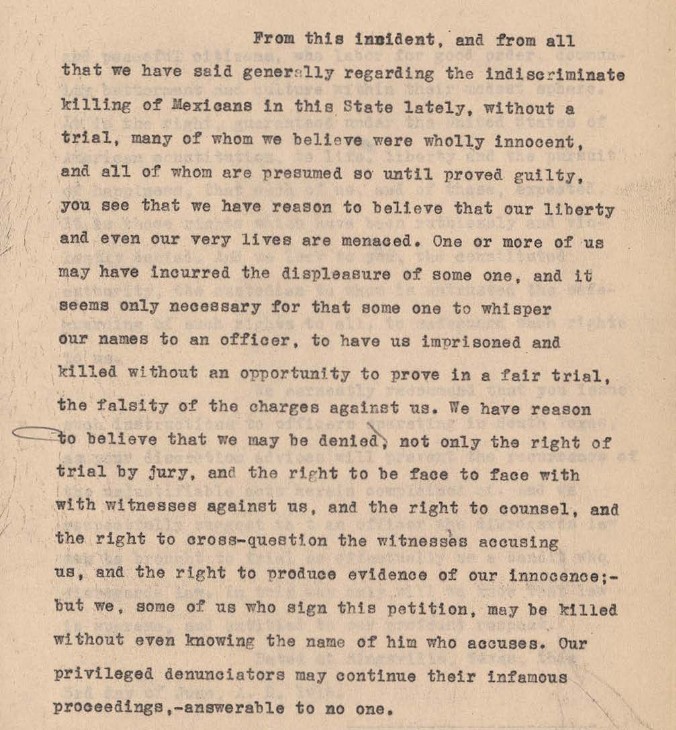

But others acknowledged the racial dimensions of this case and its place as part of a pattern of state sanctioned violence against Mexicans and Mexican Americans. Newspaper editor Manuel Gonzales had been arrested alongside Morin and Ponce, but Thomas Hook, a local Anglo lawyer, helped him get released quickly. With Hook’s help, Gonzales and others drafted a letter to President Woodrow Wilson protesting the recent widespread violence against ethnic Mexicans in Texas. They started letter with a description of the Rangers’ role in Morin and Ponce’s disappearances.

The authors told Wilson that the “indiscriminate killing of Mexicans in this State” gave them “reason to believe that our liberty and even our very lives are menaced.” They made clear that law enforcement was involved, writing “it seems only necessary for that some one to whisper our names to an officer” for them to be arrested and possibly killed without charge.

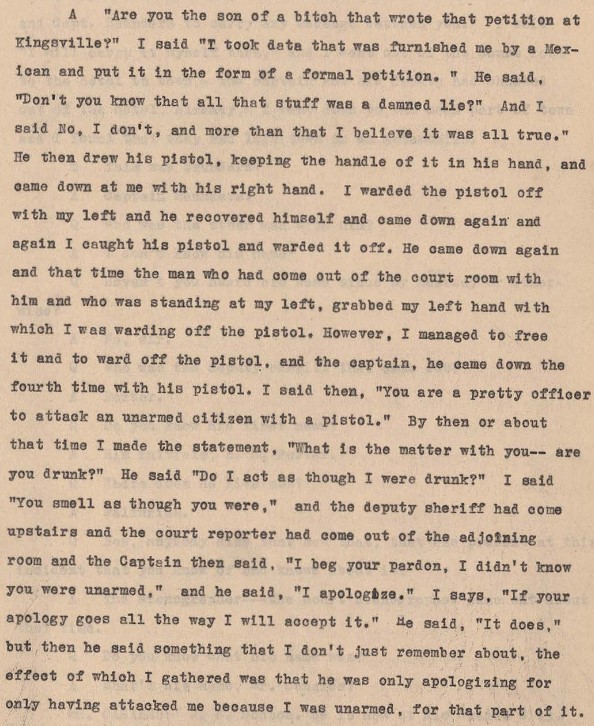

Wilson never responded, by J.J. Sanders did. Sanders encountered Hook in a local courthouse sometime later and demanded, “Are you that son of a bitch who wrote that petition at Kingsville?” Hook defended the petition, and Sanders pistol-whipped him.

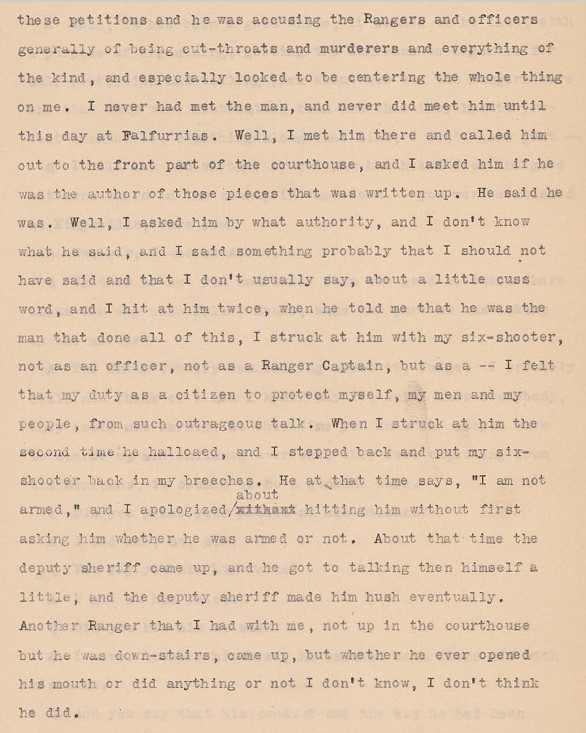

Sanders defended the attack, calling the petition signers “outlaw Mexicans” and saying the petition was entirely Hook’s idea (Canales Hearings Transcript, 1396). He claimed it was his “duty as a citizen to protect myself, my men and my people from such outrageous talk.” That Sanders felt pistol-whipping a lawyer in a courthouse was a suitable method of defense, though, just demonstrates the culture of extra-legal violence in which the Rangers operated.

Hook and Sanders both described the incident as part of the Canales investigation, 1919 state legislative hearing led by representative José Tomás Canales into Ranger violence toward Mexicans and Mexican Americans. The full hearing transcripts are online. You can read Hook’s testimony in Volume I starting on page 238 and Sanders’ testimony in Volume III starting on page 1382.

The Texas Rangers have a long history of attacking civilians and ignoring the rule of law, as JJ Sanders did to José Morin, Victoriano Ponce, Manuel Gonzales, and Thomas Hook and this year Refusing to Forget is documenting it. Explore this blog or follow @Refusing2Forget on Twitter to learn more.