On May 20, 1974, the US Supreme Court decided against the Texas Rangers in Allee v Medrano, upholding a lower court’s ruling that the Rangers injured strikers constitutional rights during the 1966-1967 Starr County melon strikes.

In the 1960s Tejano farmworkers in Starr County, Texas, worked in terrible conditions for wages as low as $0.50/hour. Most lived in homes without electricity or running water and had little to no access to school or medical care. Starting in June 1966, the workers struck for better working conditions and higher wages in partnership with the United Farm Workers. Law enforcement hassled and threatened organizers and strikers from the start, as seen in this quote/these quotes from the 1974 Supreme Court decision:

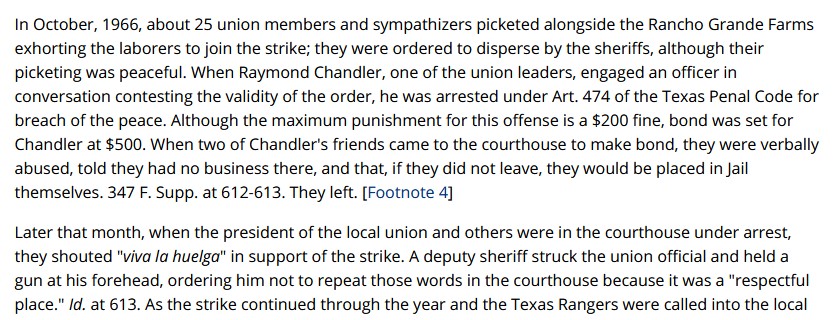

Rangers under Capt. Alfred Y. Allee, Sr. arrived in Starr County in May 1967 to ‘protect’ that year’s harvest at the request of the county attorney, who was also on retainer for one of the biggest melon growers. In his book Cult of Glory: The Bold and Brutal History of the Texas Rangers, Doug Swanson describes Alle as an experienced Ranger who cared about his men’s safety and about law and order—and as a violent man with a strong hatred of Mexicans and Mexican Americans.

Allee showed fierce loyalty to the men who worked for him. He defended them against all critics, bought them lunch on the road, and went to funerals of their loved ones. “I mean he guarded over us men like a sitting hen,” [Joaquin] Jackson said. In hazardous encounters, Allee walked point. “If there was going to be a firefight or there was gonna be any trouble, he’d be out in front,” Jackson said. “He always said no one is going to kill one of my men without killing me first.”

…

To many Latinos in South Texas, Allee did little to dispel their fear and mistrust of the Rangers. José Ángel Gutiérrez recalled the captain’s confronting—and allegedly shoving—the Hispanic mayor of Crystal City at a rowdy city council meeting. “[Allee] tells him, ‘You goddamn Mexican. Tell these goddamn Mexicans to shut up,” Gutiérrez said. “Something made Allee hate Mexicans.”

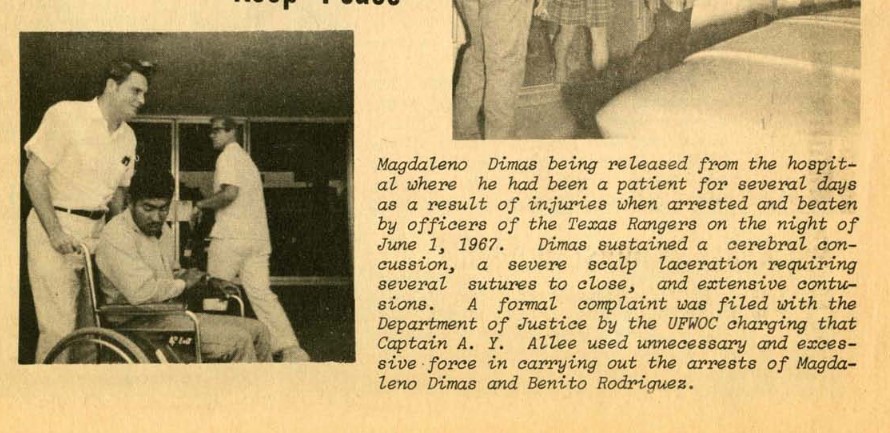

The treatment of strikers, organizers, and their supporters under Allee was violent. Later in May 1967, he arrested Rev. Edgar Krueger of the Texas Council of Churches, and, while in custody, another Ranger held Krueger’s face just inches from a passing train. Rangers did the same to Magdaleno Dimas, a union supporter and ex-con whom Allee considered dangerous.

Sometime after the train incident, Rangers attempted to arrest Dimas for brandishing a gun, but they had no grounds for a warrant. Instead, they tailed other union supporters to a house where Dimas was, called a justice of the peace to fill out warrant forms so they could enter, arrested Dimas and another union member, and beat Dimas so brutally that “his spine was curved out of shape” (see SCOTUS excerpt below). Allee claimed Dimas had tripped during the arrest (Swanson, 368).

Law enforcement took other public anti-union positions. The Starr County Sheriff’s Office distributed an anti-union paper. The Rangers selectively enforced the unlawful assembly laws to penalize union members and solicited baseless accusations against them from people with no knowledge of the alleged offenses, as the Supreme Court decision recounts:

Government bodies condemned the Rangers’ behavior, and state senators requested that the Rangers be removed from the area. The US Commission Civil Rights concluded that the Rangers had denied farmworkers their rights. In 1972, a Texas court agreed, and the US Supreme court upheld that decision two years later. They concluded that the Rangers had deprived union members of their rights through a “prevailing pattern” of violence, intimidation, and coercion.

The Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum’s biography of Allee mentions the strikebreaking but gives Allee the last word. He’s quoted as claiming he “didn’t mishandle any people.”

And yet it is well-documented that the Texas Rangers participated in violent, illegal strikebreaking in the 1960s. Learn more about the 1966 strike and its history from the National Parks Service. Explore this blog or follow @Refusing2Forget on Twitter to learn more about the complex and often violent history of the Texas Rangers.