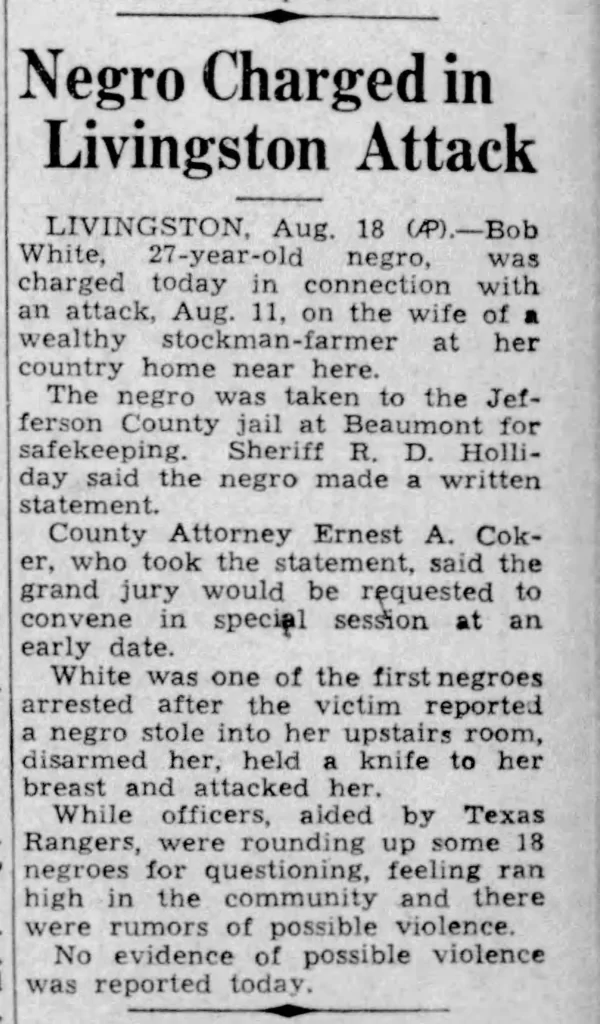

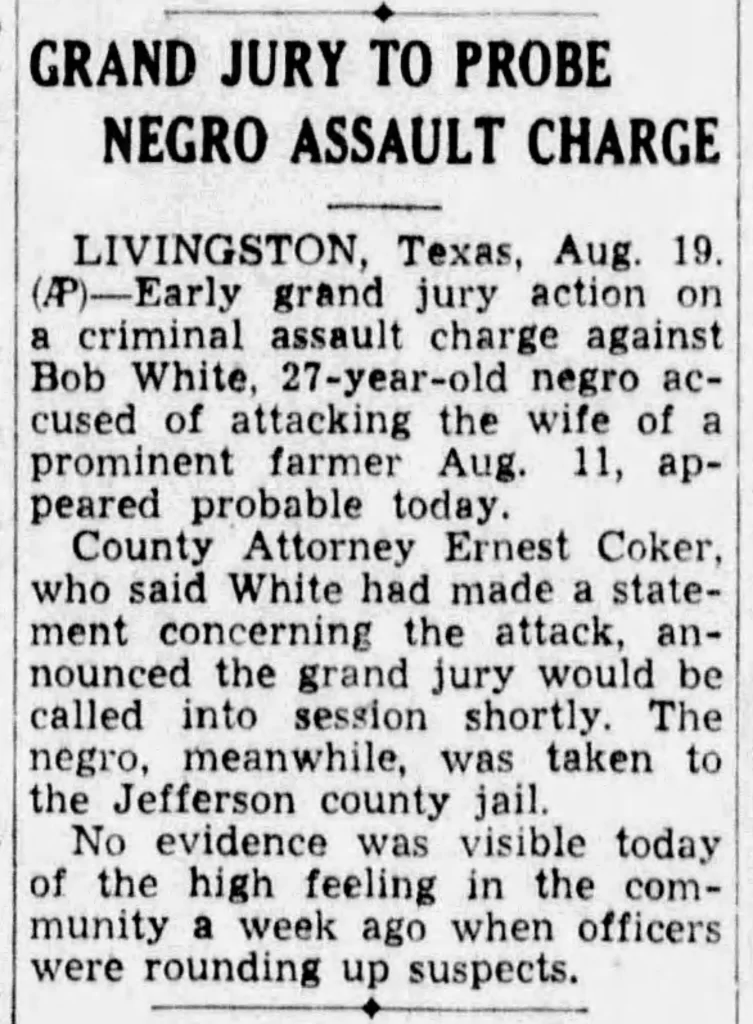

#OTD in 1937, Bob White, a Black farmworker, was found guilty of rape and sentenced to death based on a forced confession extracted with the help of Texas Rangers. Though little remembered, the case is one of two Supreme Court rulings against Ranger conduct.

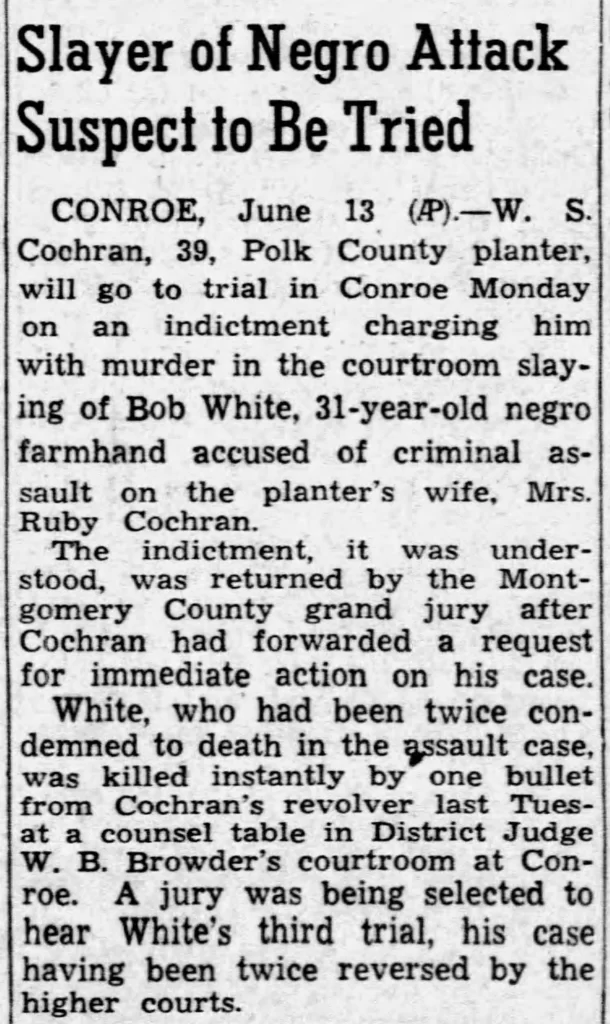

In August 1937, White was arrested in Polk County, Texas, for the alleged rape of his employer’s white wife, Ruby Cochran. Eventually his conviction was overturned, retried, and overturned again, before he was shot and killed in a Conroe courtroom by Cochran’s husband.

Police had no physical evidence to support White’s arrest, and, instead, relied solely upon Mrs. Cochran’s memory of her assailant’s voice.

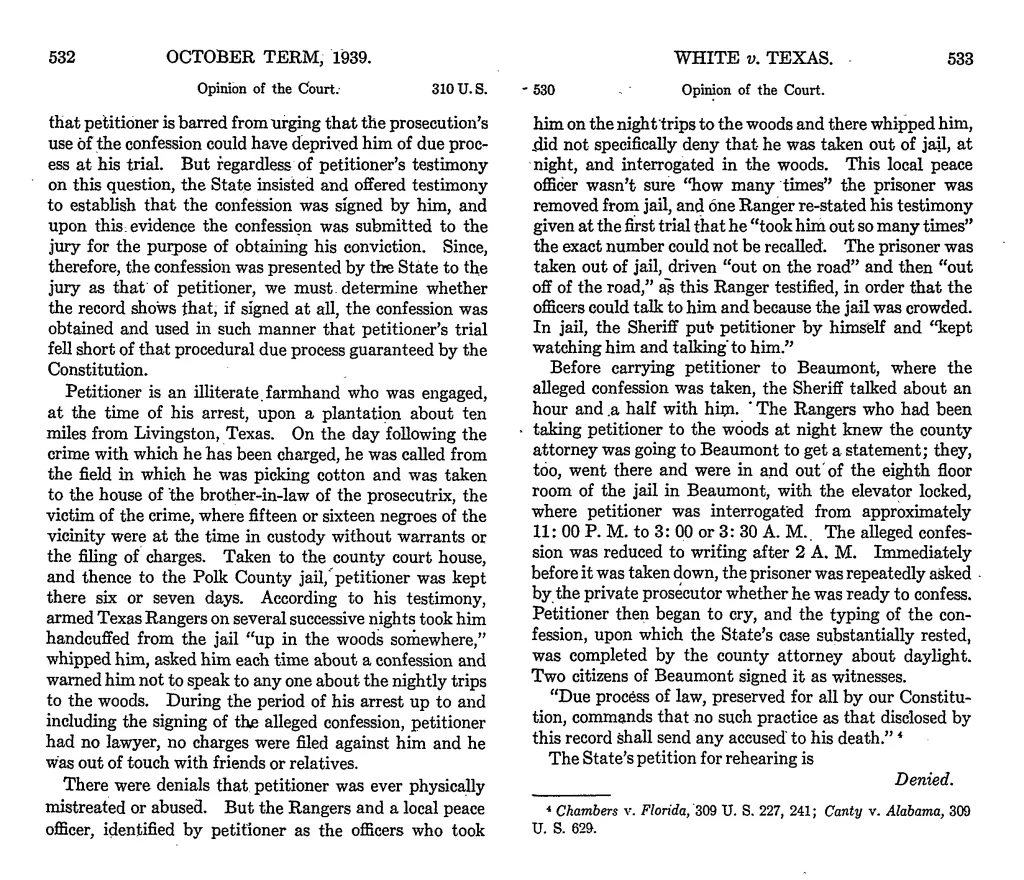

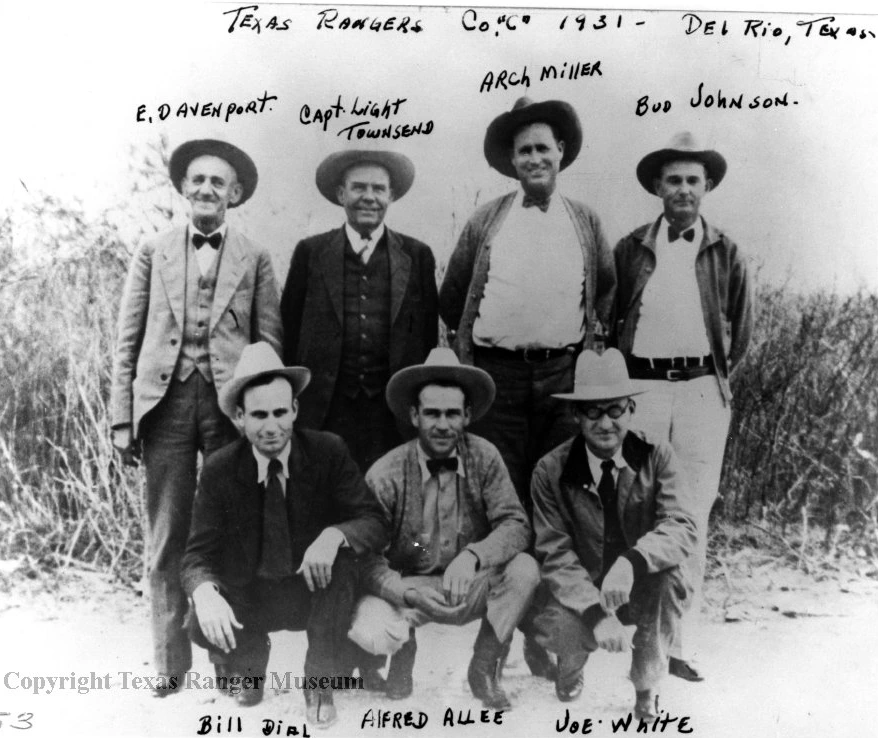

In order to build a case against White, Polk County deputy Coleman Weeks worked with Texas Rangers Maro Williamson and Edward Davenport to force White’s confession.

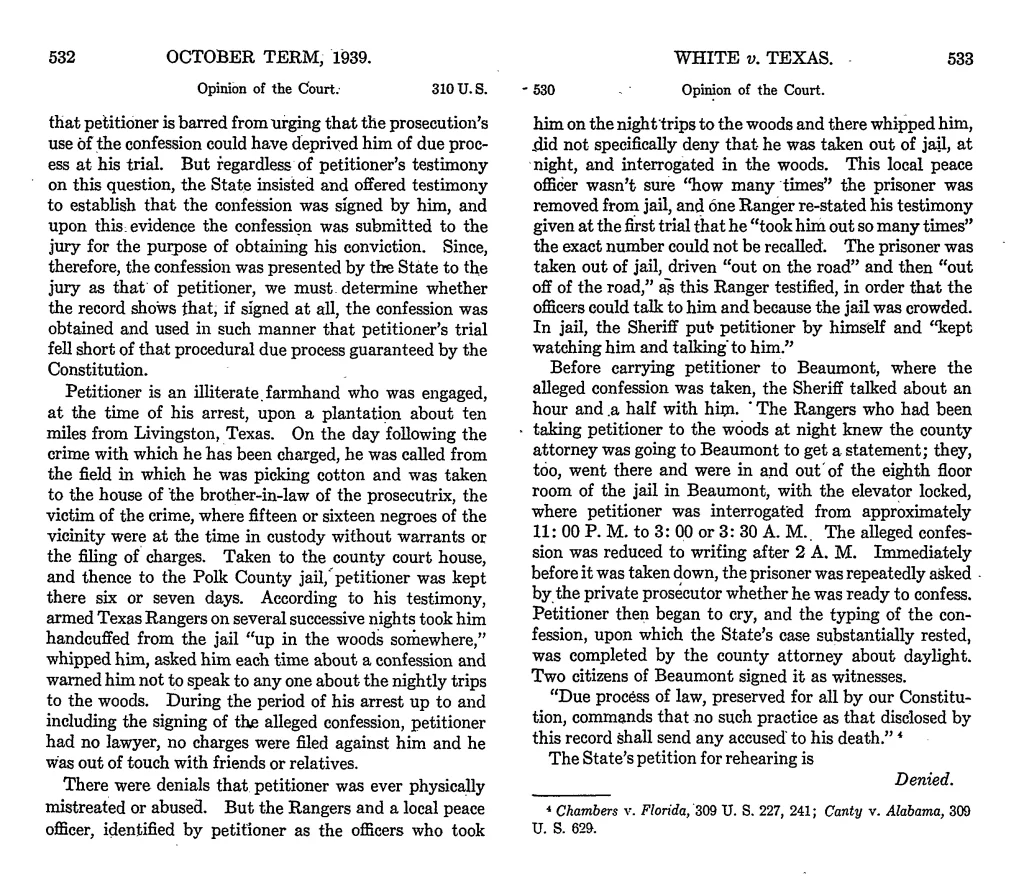

Beginning the day of his arrest and continuing for at least four days thereafter, White was taken from his jail cell, chained to a tree, and severely beaten by Williamson and Davenport in an effort to extort a confession.

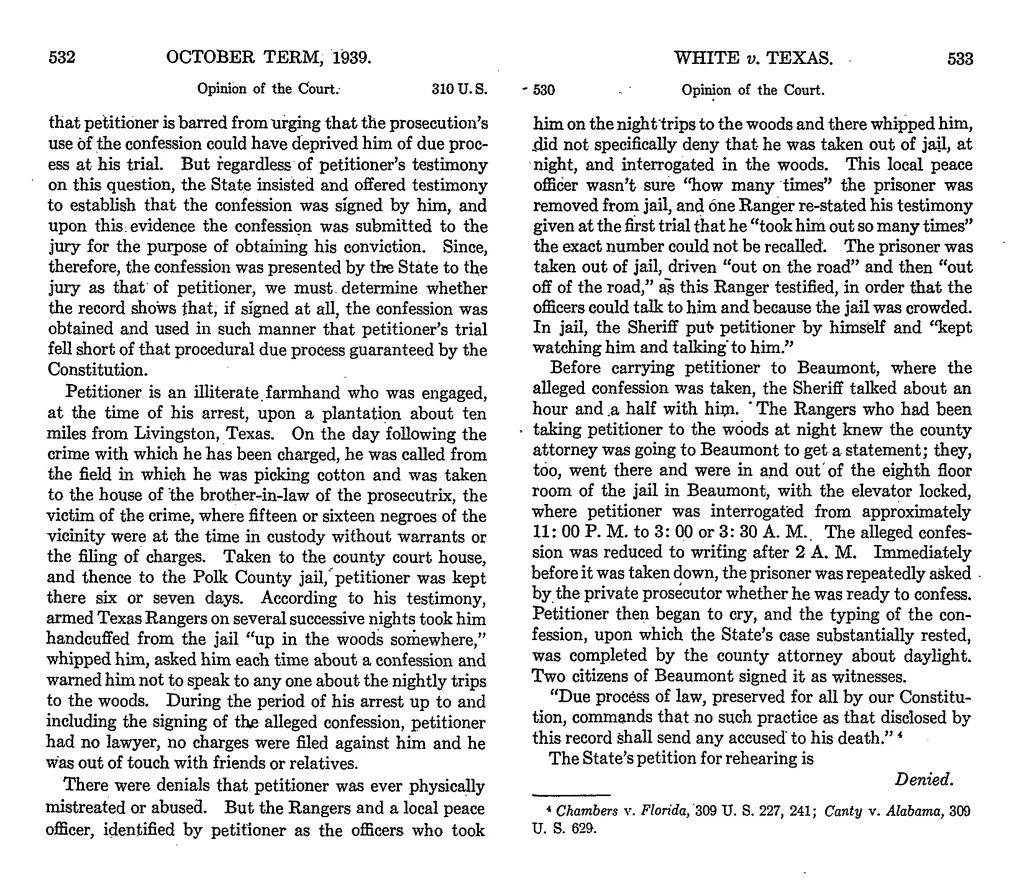

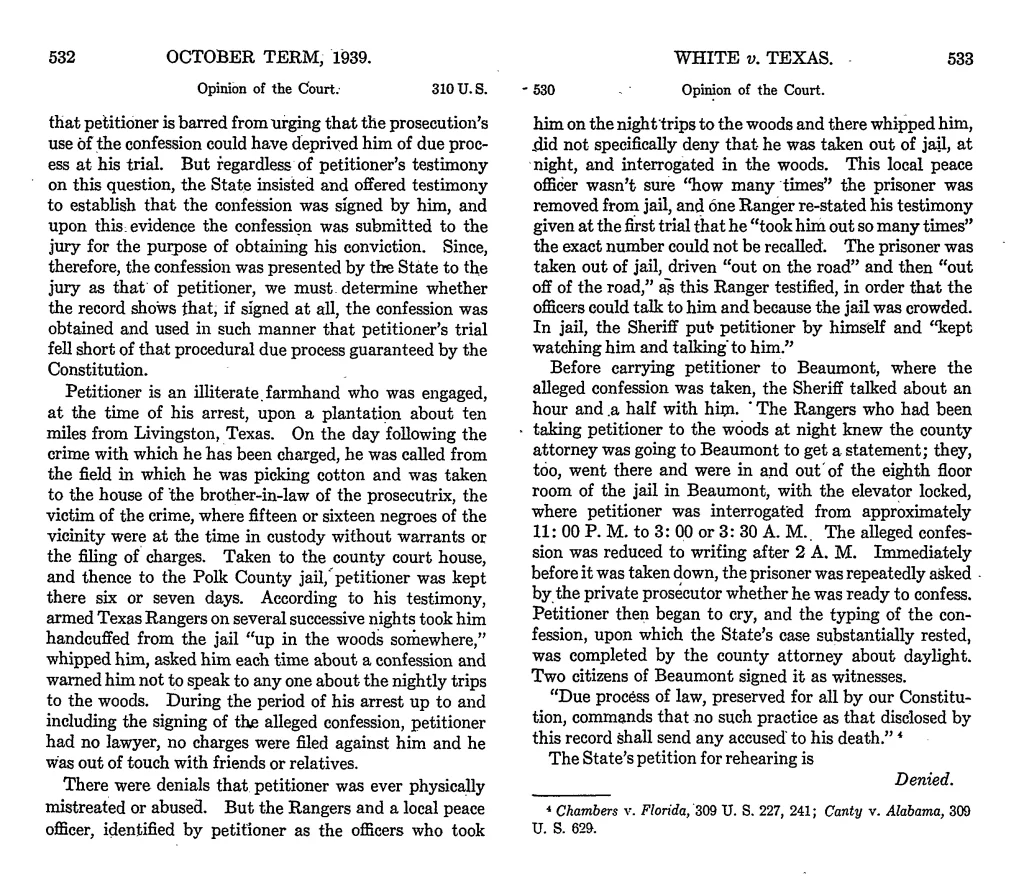

Although White maintained his innocence, Polk County Sheriff Roscoe D. Holliday continued to press for a confession, and county prosecutor Ernest Coker took White to Beaumont to force a statement.

Rangers Williamson and Davenport accompanied Coker and White to the Beaumont jail and were in the room when White endured a four-hour, middle-of-the-night interrogation by special prosecutor Zimmie L. Foreman without an attorney.

Prosecutor Foreman had been hired by the Cochran family to secure a confession from White. At 2:00 a.m., Foreman dictated a confession for White and county attorney Coker recorded it. White then put his “X” mark on it without knowing what it said. He could not read or write.

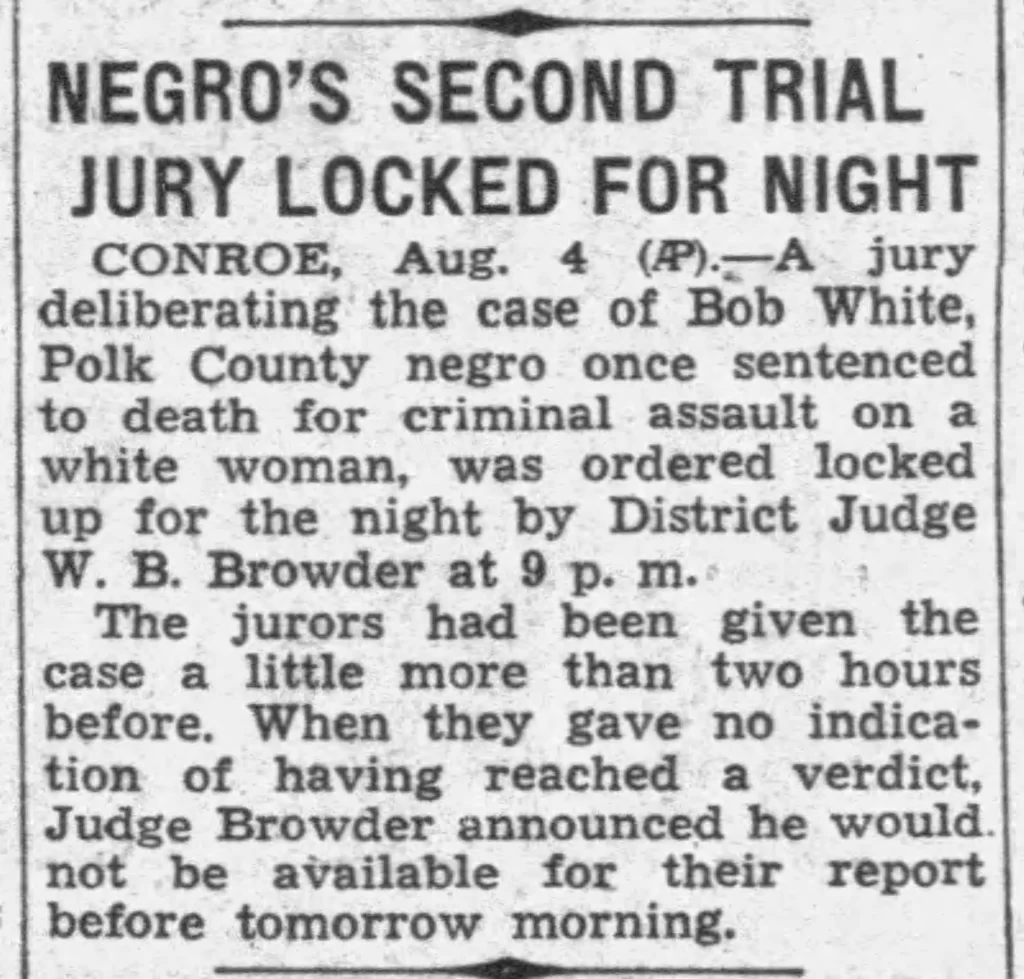

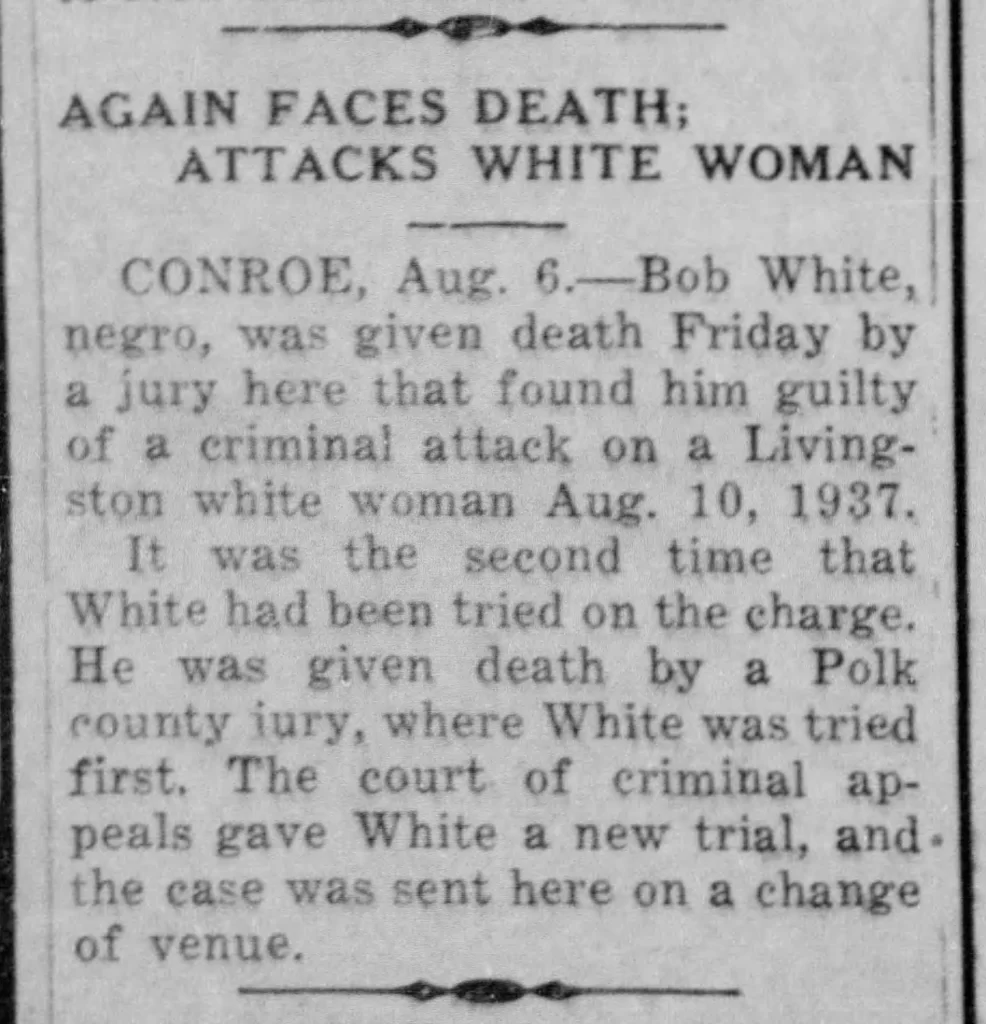

OTD in 1937, White’s case was tried in Livingston before Judge W.B. Browder and an all-white jury. The jury found White guilty and called for the death penalty. The key evidence proved to be the forced confession extracted by prosecutors and the Texas Rangers.

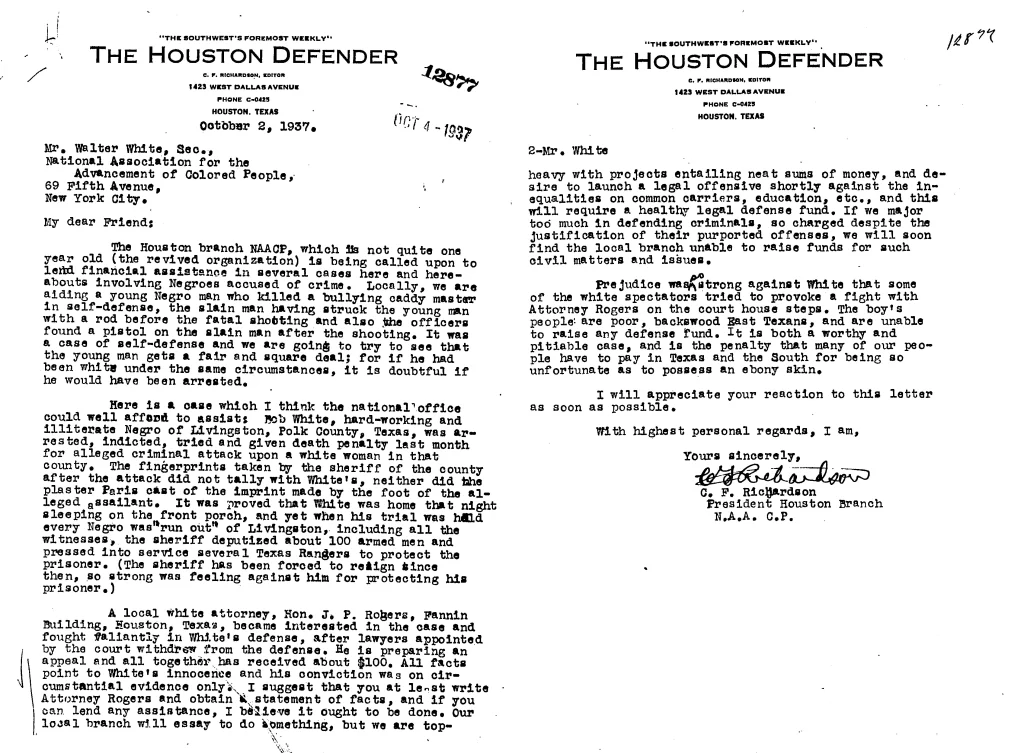

Backed by the @NAACP, White’s lawyer, J.P. Rogers of Houston, appealed the case because his client’s due process rights had been violated. On April 16, 1938, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals overturned the verdict and sent the case to be retried in another location.

White’s second trial was moved to Conroe. There, on August 2, 1938, he was tried before an all-white Montgomery County jury. Zimmie Foreman led the prosecution’s effort, focusing on the alleged confession White had made.

Defense attorney J.P. Rogers called White to the stand. White testified that deputy Weeks and Rangers Williamson and Davenport had repeatedly taken him into the woods and beaten him to extract a confession. He also showed the court his scars from the beatings.

Although Polk County Sheriff Roscoe Holliday testified that all of White’s allegations were lies, Ranger Williamson admitted that he and Davenport had pressed for a confession.

“We took him out of jail to talk to him,” Williamson said. “The jail was crowded. There was lots of them in there and we took them out where we would be by ourselves, to talk to him.” Deputy Weeks confirmed this account.

Despite White’s testimony and Williamson’s acknowledgement that extraordinary measures had been taken to get a confession, the all-white Conroe jury found White guilty, and he was again sentenced to death.

White’s attorney, J.P. Rogers, appealed this most recent finding to the U.S. Supreme Court, claiming that his client’s due process rights had again been violated.

The Court agreed and on March 25, 1940, issued the following statement. “Due process of law, preserved for all by our Constitution, commands that no such practice as that disclosed by this record shall send any accused to his death.”

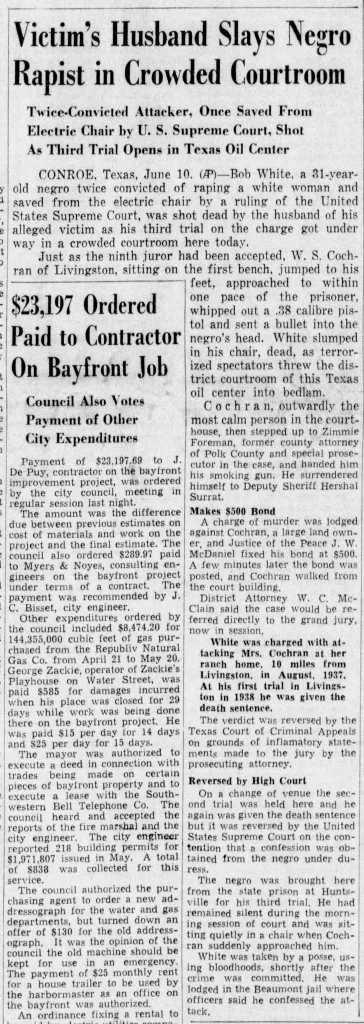

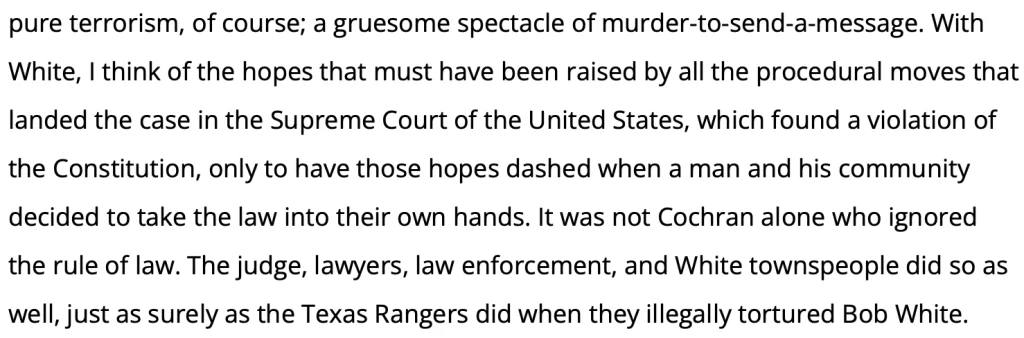

The U.S. Supreme Court ordered a new trial, and the case returned to the Conroe courthouse on June 11, 1941. As Bob White sat in chains at the front of the courtroom, W.S. “Dude” Cochran, Ruby’s husband, approached and shot him in the head. White died instantly.

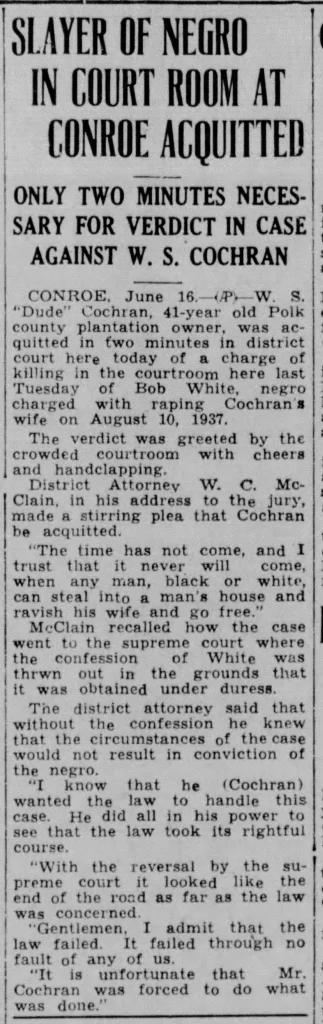

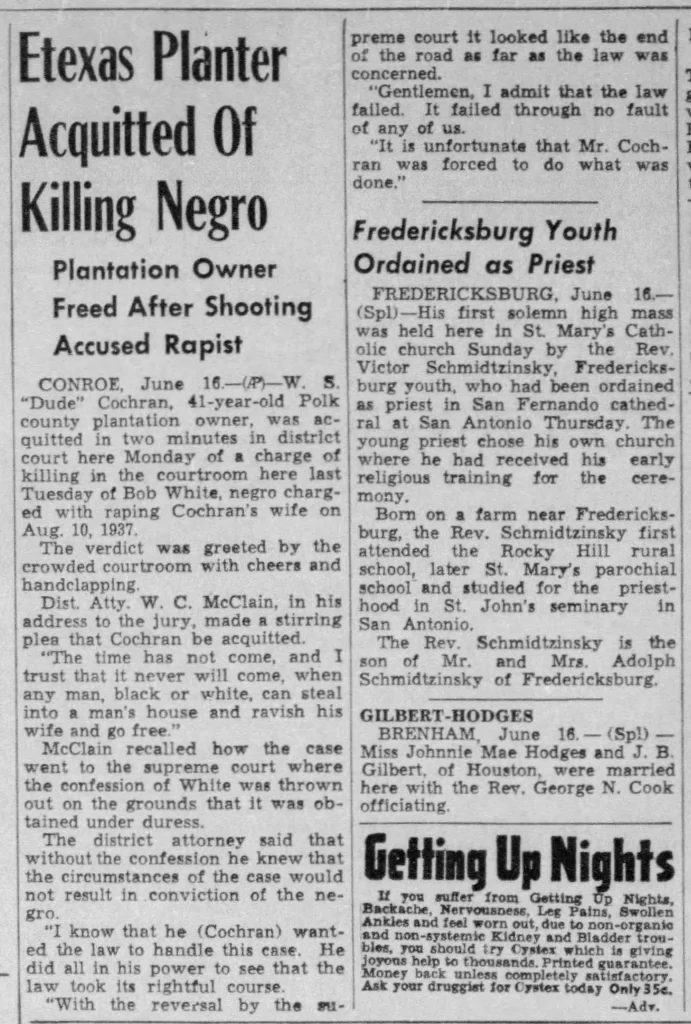

A week later, an all-white Montgomery County jury found Cochran innocent of any crime. The county district attorney, W. Cleo McClain, actually encouraged the exoneration.

“It is unfortunate that Mr. Cochran was forced to do what was done,” McClain said. “I know that he (Cochran) wanted the law to handle this case. He did all in his power to see that the law took its rightful course.”

McClain then told the jurors: “With the reversal by the supreme court it looked like the end of the road as far as the law was concerned.” By McClain’s logic – the logic of lynching — Cochran had to act.

“These events tore at the heart of the Black community in Conroe and Livingston,” writes @agordonreed, who grew up in their aftermath. The Supreme Court’s intervention raised hopes for basic fairness, only to be dashed.

Gordon-Reed’s family was not alone in avoiding Conroe after this crime perpetrated by private citizens, judges, prosecutors, and Texas Rangers.

But Black Texans also resisted. 40 miles away and 6 weeks after White’s murder, Houston dentist and @NAACP leader Lonnie Smith attempted to vote in the all-white Democratic primary.

Smith was denied, but backed by the @NAACP he sued and won a landmark civil rights victory in the Supreme court, striking down the all-white primary. https://www.lonestarhighcourt.org/smith-v-allwright-1944

Subsequent civil rights victories changed the hearts and minds of some white Texans. @agordonreed never forgot about White’s murder, but was supported by white teachers when she integrated Conroe’s schools a generation later. https://wwnorton.com/books/9781631498831

In 2022, Conroe named a school after her; the county that tolerated the torture and murder in open court of Bob White a generation before, and the burning at the stake of another Black man on the courthouse lawn a generation before that, had changed.

Yet the @txrangermuseum does not mention the White case, one of two times Ranger conduct has been at the center of a U.S. Supreme Court case, in any of its displays or online materials that we can find. (They do mention the other.) https://refusingtoforget.org/decision-in-allee-v-medrano/

As Mickey Friedman writes in a review of @agordonreed’s “Juneteenth,” this erasure means that the obvious horror of White’s murder is followed by a second, “the insistence that the lies prevail.”

![Mickey Friedman on Annette Gordon-Reed’s “Juneteenth.” https://theberkshireedge.com/bso-announces-2021-22-symphony-hall-season]](https://refusingtoforget.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/025-Friedman-on-Juneteenth-1024x665.webp)

We refuse to forget Bob White and insist that his life and death are critical chapters in the histories of Texas, the United States, and the @TxDPS’ Texas Rangers.

This thread is a part of the #OTD in Ranger history campaign that @Refusing2Forget is running this year. Follow this twitter handle or https://refusingtoforget.org/ranger-bicentennial-project/ and visit our website https://refusingtoforget.org to learn more.

Key sources for this entry are @agordonreed’s https://wwnorton.com/books/9781631498831, Nick Davies, White Lies: Rape, Murder, and Justice Texas Style https://www.amazon.com/WHITE-LIES-Nick-Davies/dp/0679401679.

Refusing to Forget members are @ccarmonawriter @carmona2208 @acerift @soniahistoria @BenjaminHJohns1 @LeahLochoa @MonicaMnzMtz and @Alacranita, another co-founder is @GonzalesT956.

@emmpask @sdcroll @HistoryBrian @LorienTinuviel @hangryhistorian, @ddsanchez432,

@elprofeml, and @littlejohnjeff are other scholars working on this project.