#OTD on February 13, 1919, the final day of the Joint Committee of the Senate and the House in the Investigation of the Texas State Ranger Force (hereafter, “Canales Hearings”) took place in the Railroad Commission Hearing Room on the 2nd floor of the state capitol.

Todays’ thread summarizes both this day’s testimony, and some of the outcomes of the hearings.

Ranger leaders offered some of their most explicit justifications of violence against unarmed civilians. Captain J.J. Sanders pistol-whipped attorney Thomas Hook in the hallways of the Falfurrias courthouse in May 1916.

Hook’s “crime” was helping Kingsville residents to send a petition to President Wilson and Governor Ferguson asking for protection against arbitrary violence by Rangers and vigilantes.

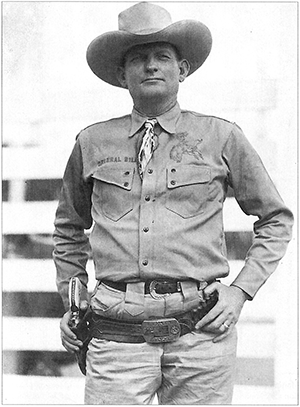

Sanders and W.W. Sterling, a rancher who would later become Adjutant General of the Rangers, defended the assault, with Sterling denying that Hook was “an honorable, desirable citizen to white Americans,” but instead a “religious fanatic.”

Canales himself was a subject of discussion, with Ranger leaders repeatedly alleging that he, political boss James Wells, and local officials such as Sheriff W. T. Vann did not act against seditionists or draft dodgers.

Numerous committee members also criticized the Ranger force, expressing incredulity at the photos of Rangers on horseback with corpses at their feet and at the disappearance of Florencia García while under the custody of George Saddler and John Sittre.

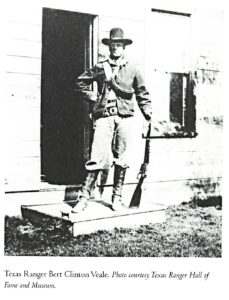

Canales brought up the astonishing events of the previous weekend, when four Rangers left the hearings, gambled, drank (which was illegal given statewide Prohibition), and ended up in a brawl in which Private Bert C. Veale was killed by a fellow Ranger.

Canales again returned to the stand, defending himself against charges that he wanted to eliminate the Ranger Force; he maintained that his goal was to reform it. With testimony over, Canales entered more affidavits into the record.

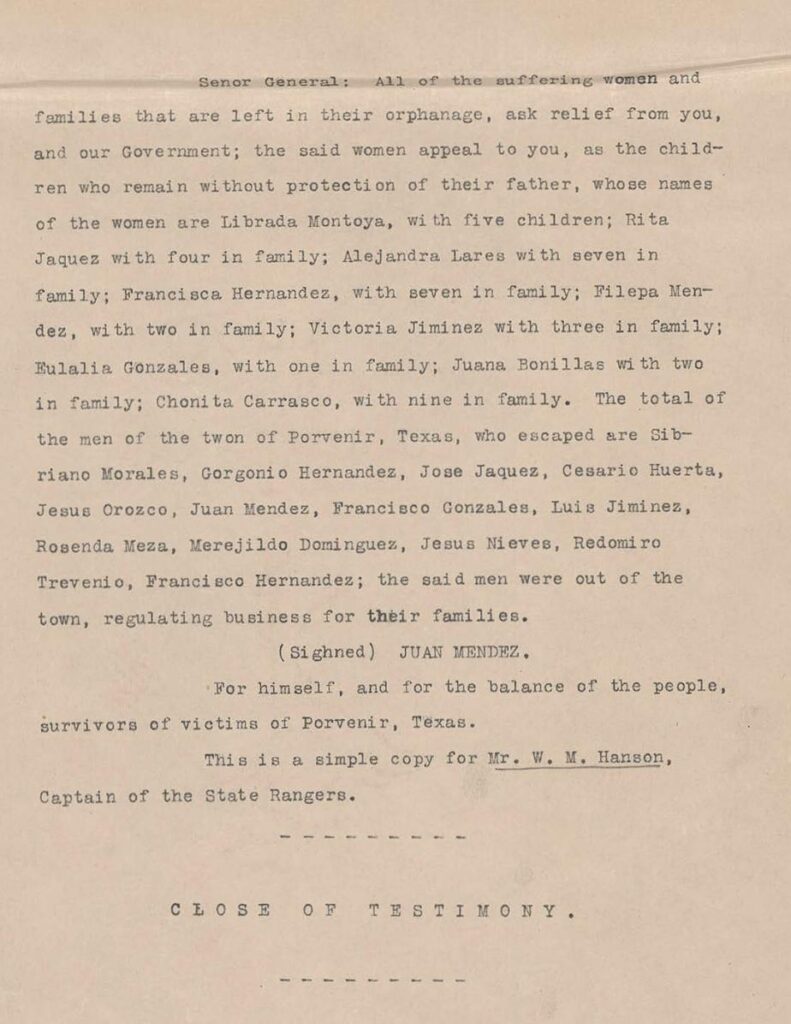

The last items in the proceedings are harrowing accounts of the Porvenir Massacre given by former residents who fled to Mexico. Perhaps it is appropriate that Juan Mendez has the last word, signing his account “For himself, and for the balance of the people, survivors of victims of Porvenir, Texas.”

The impact of these historic proceedings on the Rangers and law enforcement were mixed. On the one hand, the most thorough reforms were not passed, the committee praised the leadership of the Ranger force, and no criminal prosecutions resulted from the evidence unearthed.

The committee made major changes to Canales’ proposed legislation, stripping it of his provisions for local control and the bonding of Rangers. The revised legislation reduced the size of the Ranger Force, but allowed for its expansion in the event of an emergency.

“Vindication complete!” crowed one Ranger Captain in a telegram to a supporter. “I do not recognize my child,” Canales later said of the watered-down legislation. Rangers like James Monroe Fox, who oversaw mass murder, would later be re-hired.

On the other hand, the committee made the unprecedented admission that “the Rangers have become guilty of, and are responsible for, the gross violation of both civil and criminal laws of the state.”

Moreover, the Adjutant General canceled the appointments of almost all “Special Rangers” because of “the serious objection made against Special Rangers by the Ranger Investigation Committee and other members of the Legislature.”

This prompted Congressman Claude Hudspeth to bitterly complain to the Adjutant General that “I went to Austin and untangled the fangs of Canales from around your neck, and yet you fired all of your best captains, which included my friends.”

This ambiguous outcome reverberates in recent scholarship on the hearings. @BenjaminHJohns1, @MonicaMnzMtz, and Richard Ribb conclude that Ranger leaders were successful in fending off fundamental reform. https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674244825

On the other hand, @HistoryBrian, in his recent book https://uncpress.org/book/9781469670126/borders-of-violence-and-justice/, credits the Canales hearings with pushing the Rangers into becoming a more professional police force, constrained by sensible new laws.

But of course the subsequent history of policing in the United States, and not just in Texas, is hardly free of racism, unlawful violence, and consequent political repression. https://uncpress.org/book/9781469659176/occupied-territory/

Ranger injustices hardly ended in 1919. Some later incidents will be analyzed in the course of the #OTD in Ranger history campaign that @Refusing2Forget is running this year. Follow @Refusing2Forget, https://refusingtoforget.org/otd-calendar/, and visit https://refusingtoforget.org/ to learn more.

Key secondary sources for this thread include:

@BenjaminHJohns1’s Revolution in Texas (pp 169-175)

@MonicaMnzMtz’s The Injustice Never Leaves You (182-216)

Reverberations of Racial Violence

and Ribb, “Reader’s Guide to the Canales Hearings”