Content warning: This post contains graphic descriptions of a lynching. Please also know that images of George Hughes’ body are available on Google and use caution if you research this incident further.

On this day in 1930, Texas Ranger Frank Hamer failed to prevent the lynching of George Hughes in Sherman, Texas, or the subsequent destruction of the town’s Black commercial district.

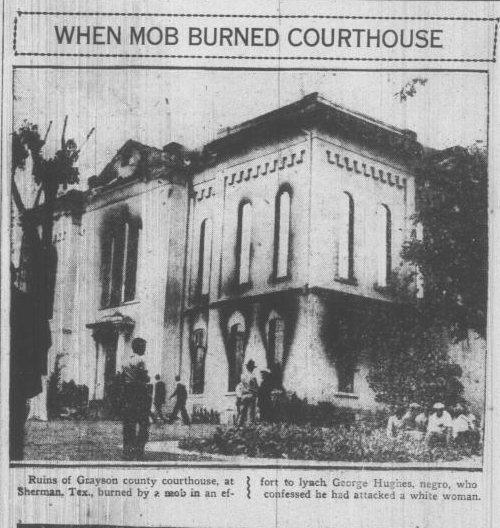

Hughes, a Black man, had been accused of raping a white woman. After his trial began on May 9, a white lynch mob invaded the courthouse and forced the trial to adjourn. Local officials locked Hughes in the Grayson County Courthouse’s walk-in vault, hoping it would protect him, and Hamer and two other Rangers guarded the stairwell to the vault. A county sheriff and some deputies were also on hand to protect the proceedings. Hughes reportedly begged for a gun with which to defend himself but did not receive one.

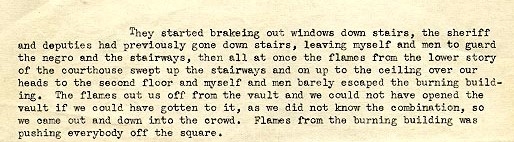

For a time, the Rangers kept the mob at bay with warning shots, but around 2:30pm the mob set the courthouse on fire. Hamer could not reach Hughes through the flams and did not know the combination to open the vault. Hughes suffocated. Hamer described the events a few days later:

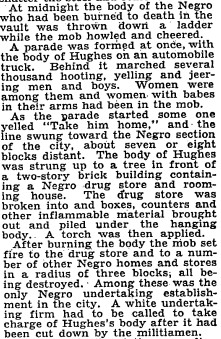

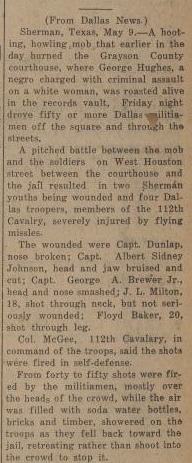

Mob members cut firemen’s hoses to prevent them from putting out the fire. When the flames died down, they broke into the vault, tied Hughes’ body behind a car, dragged it through the streets to Sherman’s Black commercial center. A crowd in the thousands, including women and children, followed. Rioters looted Black businesses, while lynch mob members hung Hughes’ body from a tree and mutilated his genitalia. They used looted items to start a fire under Hughes’ remains and partly burned his body. While some Black residents were able to defend their homes, most fled in terror. The New York Times describes the violence:

Hamer and the Rangers left town after they failed to save Hughes. They returned hours later with members of the National Guard, who engaged in a pitched battle with the mob. More guardsmen arrived on May 10, and Governor Dan Moody declared martial law through May 24:

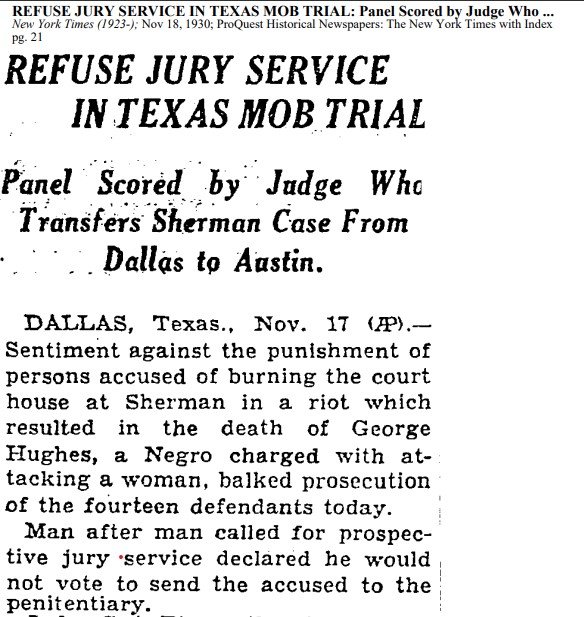

Fourteen suspected mob leaders were indicted on May 20, but the first—and only—trial didn’t begin until June 1931. The court had to move it 250 miles to Austin to find a jury willing to convict a white man in the violence. One man was eventually convicted of arson and served two years. No one was punished for Hughes’ death.

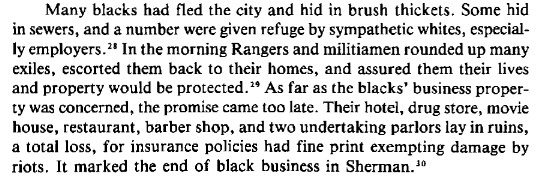

The violence and destruction devastated Sherman’s Black community. In 1987, local historian Edward Phillips called the riot “the end of Black business in Sherman”:

Grayson County Courthouse’s historical marker says the building burned in 1930 but doesn’t mention how or why. In 2025, 95 years after the Riot, a new historical marker was finally unveiled.

Today, Frank Hamer is in the Texas Ranger Museum’s Hall of Fame. As of late April 2023, his entry says nothing about the lynching or Hamer’s inability to stop it. His failure contradicts the famous ‘one riot; one ranger’ boast that one Ranger’s presence was enough to stop violence.

The lynching of George Hughes was part of what historian William Carrigan calls Texas’ “lynching culture”: the widespread use and popular glorification of extrajudicial violence to enforce Anglo supremacy over Mexican, Black, and Indigenous people. The Texas Rangers helped create this lynching culture through decades of extralegal ‘justice,’ and the celebratory stories about their exploits obscure our knowledge of the violence they participated in.

Explore this blog or follow @Refusing2Forget on Twitter to learn more.

Most of the sources in this post come from the Portal to Texas History. Hamer’s statement and other related documents are online through the Texas State Library.