Guest Blogger George Diaz on Law Enforcement Legacies of 1910s Violence.

In Américo Parades’s classic novel George Washington Gómez, we meet Feliciano García, a former sedicioso who survives the violence of the era and settles down to a quiet life caring for the family of his murdered brother. Reading of Feliciano’s life as a stepfather working a bar made me wonder what happened to the sediciosos who survived the state attacks that crushed the rebellion. Were they, as Parades depicts, able to live the rest of their lives in peace?

Because we don’t know the identity of many of the raiders, it is difficult to determine what happened to them afterward. What is certain is that area law enforcement perceived sediciosos in many of their subsequent engagements. The Texas Rangers, U.S. Customs agents, county law enforcement personnel, and soldiers [who ethnic Mexicans collectively called rinches] didn’t hang up their guns in 1916. Many continued to serve and believed that alleged local law breakers were former sediciosos regardless if their offense bore little resemblance to the targeted raids attributed to the Plan de San Diego uprising. Smugglers, in particular, bore the brunt of officers’ attacks.

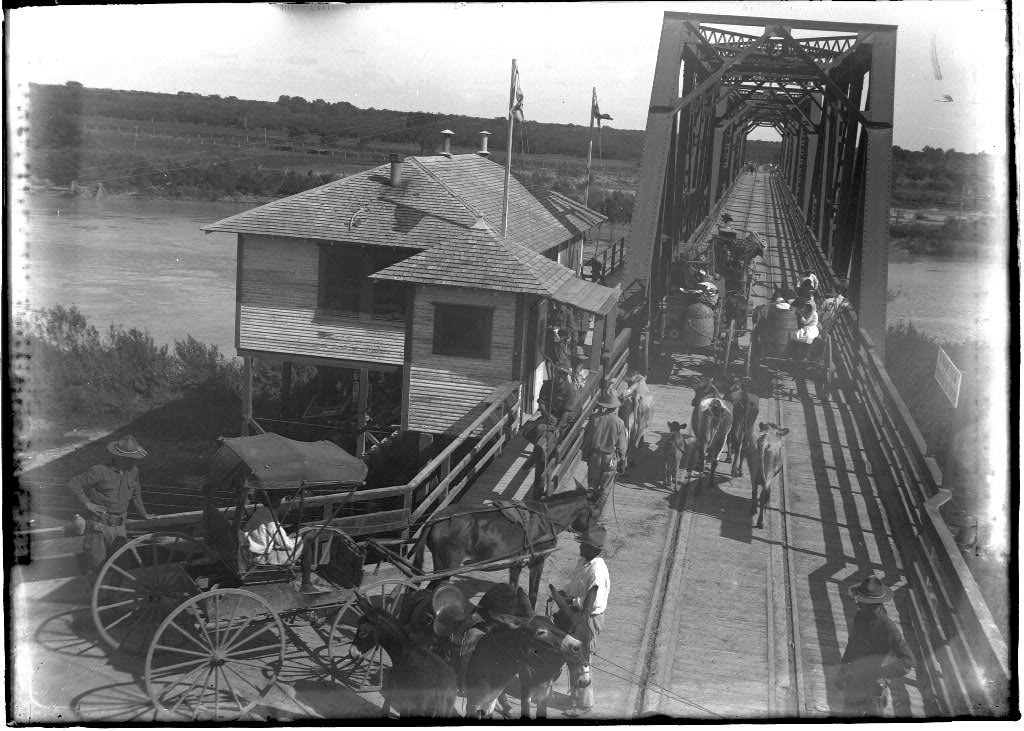

Smuggling across the Rio Grande is as old as the border itself. In the 19th century, both Mexico and the United States gathered most of their national revenue from tariffs. These trade taxes fell acutely on border people who felt the pinch each time they tried to cross goods from one side of the river to the other. With trade fees as high as 20% on certain items, many people crossed goods clandestinely to save money, thereby transforming licit items such as piloncillo and calico into contraband. Although popularly accepted, smuggling remained a crime under the law and officers on the U.S. side fined and arrested illicit traders when they could. U.S. anti-smuggling efforts of the era primarily took the form of policing trade and collecting tariffs and was a routine nonviolent affair.

Illicit trade transformed in the 1910s. In 1913 Congress approved the 16th Amendment to the Constitution, thereby instituting a national income tax. That same year, tariff reform reduced or dropped many trade taxes, thus alleviating the cause of much of the petty smuggling on the border. These changes in U.S. trade policy freed the Customs Service to perform more mounted patrols and interdict the trafficking of weapons out of the country. This, coupled with the spilling of the Mexican Revolution onto U.S. soil, prompted the Customs Service on the border to depart from its traditional duties as agents of economic security and act more as a national security force.

It is important to point out that smugglers acted very differently than sediciosos. Whereas sediciosos attacked targets, smugglers worked secretly evading rather than engaging state forces. Despite this, area law enforcement viewed virtually any Mexican in the monte as suspect, shooting first and asking questions later. These state attacks continued after the 1915 raids ceased and persisted into Prohibition. In April 1920 U.S. Customs agents shot and killed three Mexicans in southeastern Webb County who, officers claim, were returning from smuggling liquor. English language newspapers make no mention of alcohol recovered off the victims, but labeled the dead as smugglers all the same.

Along the Rio Grande, tequileros filled the niche that bootleggers and rumrunners did throughout the rest of Prohibition era America. Unlike bootleggers and rumrunners, who generally used cars and boats to smuggle, tequileros were Mexican and Mexican Americans who relied on mules and donkeys to carry their contraband cargo. Many came from modest rural backgrounds and smuggled to supplement their limited income. Although tequileros took back country trails and often traveled at night to avoid confrontation, Texas Rangers and mounted Customs agents saw smugglers caravans and believed that the sediciosos had returned to kill more gringos. Texas Ranger Captain William Warren Sterling, himself a veteran of the Plan de San Diego, put it simply: tequileros “had to be dealt with as foreign enemies, not as ordinary domestic bootleggers.”[1]

Rather than see tequilero forays as opportunistic smuggling ventures, regional law enforcement viewed them as invaders and attacked them violently. Between May of 1919 and the end of Prohibition in 1933, the state waged an unprecedented war against smugglers in south Texas that left nine tequileros dead and at least a dozen wounded. Despite officers statements that tequileros shot first, mounted smugglers failed to kill or even wound a single law enforcement agent in these encounters, suggesting that Texas Rangers and Customs agents killed by ambush.

Officers involved in these killings rarely answered for their actions and faced light repercussions in the few instances their attacks were investigated. On a clear morning on April 8, 1919, 2nd Lt. Robert L. Gulley spied several persons pushing a raft across the Rio Grande during a cavalry patrol near Havana, Texas. Suspecting the raft carried contraband mescal, Gulley ordered fire mortally wounding Concepción García, a young girl. A court martial found Gulley guilty of manslaughter and ordered his dismissal from service, but a presidential decision reversed the sentence and reinstated him. Seven years after Concepción’s death, the U.S. government paid her parents $2,000, without interest, for their loss.

Smugglers served as proxy sediciosos in the minds of U.S. state forces, who continued their war against them well after the Plan de San Diego raids ceased. Some smugglers may have been former sedicisos, but even so they acted very differently than the raiders of the 1910s. Like smugglers of earlier eras, they preferred discretion to confrontation. Despite this, officers actively sought them out and justified their violence by dubbing their victims smugglers whether or not they engaged in illicit trade. This aggressive, violent, and racialized pattern is another legacy of the violence of the 1910s.

George T. Díaz is Assistant Professor of History at Sam Houston State University. He is the author of Border Contraband: A History of Smuggling across the Rio Grande.

[1] William Warren Sterling, The Trails and Trials of a Texas Ranger (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1959), 84.