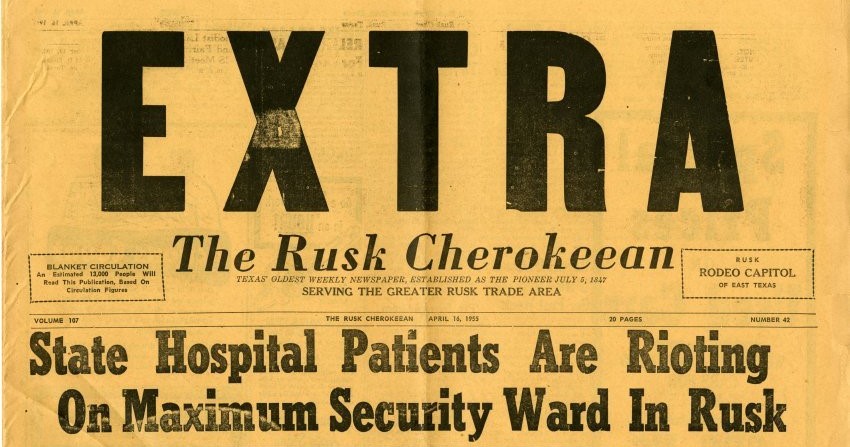

On this day in 1955, Texas Ranger Robert A. “Bob” Crowder negotiated an end to a revolt at the Rusk State Hospital for the ‘criminally insane’ in Rusk, TX. Black inmates took over the segregated Black ward, beat attendants, and took hostages in anger over terrible conditions. The hospital was a former prison and a racially segregated, violent, and inhuman place. Doug Swanson describes it in his book Cult of Glory.

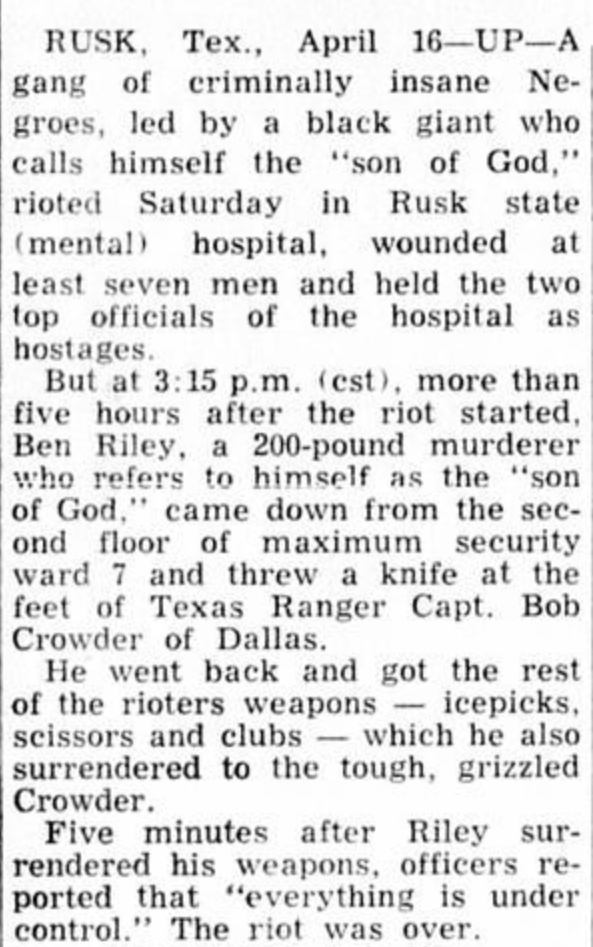

The roughly eighty inmates took hostages, killing one in the initial chaos, and began a standoff with police. The revolt was led by Ben Riley, a nineteen-year-old diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia who had killed a man when he was younger. Riley demanded to negotiate with a ranking government official but accepted Crowder as an alternative. Crowder entered the hospital yard alone (but backed up by a sniper) and promised a fair hearing about the inmates’ grievances if they surrendered. They agreed.

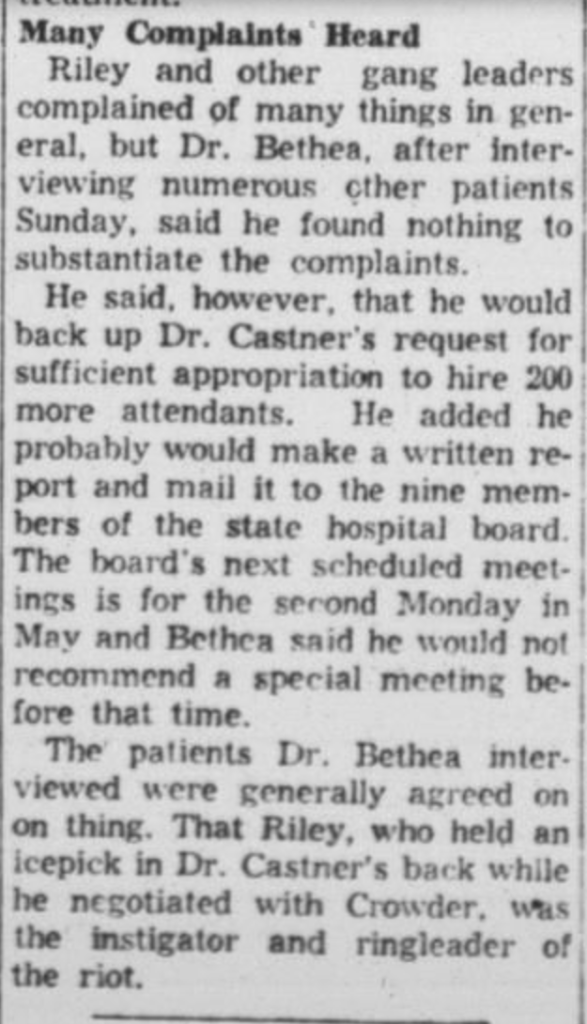

That fair hearing never happened. Instead, the state hospital board’s executive director briefly visited Rusk and decided the only necessary change was more security. Riley was put in twenty-four solitary confinement, electroshocked, and forcibly given a powerful antipsychotic.

Did Crowder believe his promise of a fair hearing? Unclear. But his reputation soared at the image of a lone white Ranger confronting violent, insane Black men. Local news coverage describes Crowder as convincing the “200-pound-murder” Riley to “act like a human being.”

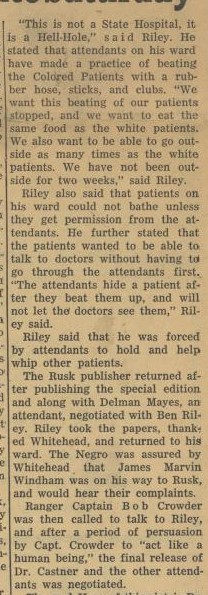

But that same article that quotes Crowder telling Riley to “act like a human being” also quotes Riley giving a very human plea for equal conditions with white inmates, the right to bathe and see doctors as needed, and a stop to the attendants’ violent attacks.

Rusk’s troubled history continued long after the revolt. In 1978, Texas Monthly published a scathing report on the hospital: careless attendants, bleak conditions, violence, and no concern for patients’ varying needs. In 2021, The Houston Chronicle published an expose about how the Texas state psychiatric hospitals fail patients. The piece uses one man’s suspicious death at Rusk as its framing example.

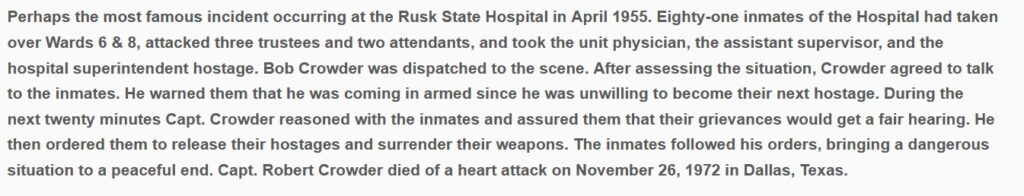

Bob Crowder isn’t responsible for decades of failure in Texas state psychiatric hospitals. But when the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum describes his “most famous incident” as “bringing a dangerous situation [at Rusk] to a peaceful end,” we need to ask, peaceful for who?

Crowder’s success has a context that that’s bigger and more complex than the Rangers’ “one riot, one Ranger” supposed success story: the purpose and restraint of Riley and other inmates; the racism and contempt for mental illness that justified segregated wards and violent ‘treatments’; the denial of a fair hearing to the inmates; and the continuity of Rusk’s problems into the present day.

To what extent did Capt. Bob Crowder really ‘save the day’ at Rusk? There’s more to the history of the Texas Rangers than simple heroics, and good history asks us to consider these complexities especially when they disrupt comfortable, simplistic narratives.

Newspaper clippings in this post come from the Portal to Texas History and the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum Online Collections. Other information comes from Doug Swanson’s book Cult of Glory. To learn more about the violent and difficult parts of the Texas Ranges’ history, explore this blog for follow @Refusing2Forget on Twitter.