Beginning in December of 1917, members of the Texas Rangers and the U.S. Army made several unauthorized incursions into Mexico while pursuing so-called bandits. On December 3, a group of military personnel pursued a group of Mexican revolutionaries under the command of Francisco “Chico” Cano across the border after the group had allegedly raided a nearby ranch. They engaged these men near the hamlet of Buena Vista and killed thirty-five Mexican “bandits” before retreating back to the U.S. side of the border. On December 31, after an alleged raid at the Indio Ranch (near Eagle Pass) a group of Texas Rangers and Army soldiers again crossed into Mexico. This time townspeople of the small Mexican town of San Jose defended themselves. They had all but routed the Americans when a machine gun platoon arrived. The machine gun cut the townsfolk down. According to newspaper accounts, the Americans “did not take the trouble to count the bandit dead, but six bodies were seen and officers say there were probably several others in the brush.”[1]

For the Rangers and Army soldiers involved in these attacks, everyone killed was a “bandit.” It didn’t matter if they were townsfolk or revolutionaries or actual desperados, they were all “bandits.” That word communicated a lot. “Bandit” by the late nineteenth had become a racial code word that over time almost exclusively referred to Mexicans and Mexican Americans. Bandits were bad people. They were killers. They didn’t care about laws or rights or justice. And once so named, mobs and law enforcement could more easily eliminate such individuals from southwestern society. Or, in the case of the two examples mentioned above, the “bandit” label meant that the Rangers and Army soldiers and others involved could be absolved of murdering large numbers of people, absolved of violating Mexico’s sovereignty after crossing the border without authorization, absolved of just about any crime against any Mexican-origin person.

One of the things that Refusing to Forget, a host of southwestern historians, and even some Ranger scholars have documented is the everyday regularity of Ranger violence against Mexicans and Mexican Americans, especially in the early twentieth century. One of the things I show in my new book Borders of Violence and Justice is that this kind of violence was sadly quotidian, that it predates the early twentieth century by decades, and that it wasn’t limited to Texas. From the 1850s to 1920s, White people across the Southwest became obsessed with supposed Mexican bandits. My contention is not that banditry didn’t exist – it did – but rather that the level of violence was far out of step with the actual threat bandits posed. Driven by fear or bloodlust or racism or some weird combination of these things, law enforcement agencies such as the Texas Rangers terrorized the Mexican-origin population in the border region. The Rangers slew a lot of people and justified that killing by claiming they had “killed some bandits.” Such claims exculpated them from possible legal challenges.

One of the problems with this lack of care or precision in the use of this terminology is that law enforcement often created the very bandits they came to fear. Many of the so-called bandits in the Southwest became bandits only after an ugly encounter with a White law officer. There are a number of prominent examples. Joaquin Murrieta was likely chased off of his mining claim by a vigilante mob acting as law enforcement and became a bandit in California in the 1850s. Tiburcio Vásquez witnessed the killing of Monterey County Constable William Hardmount in 1852 and became a bandit to survive. In Texas, the most important example of this was Juan Cortina. In July of 1859, Cortina witnessed Brownsville Town Marshal Robert Shears brutally beating a Mexican man, Tomás Cabrera, whom Cortina had employed at his ranch. Cortina intervened and ended up shooting Shears in the shoulder. “I punished his insolence and avenged my countrymen by shooting him with a pistol and stretching him at my feet, ” Cortina said. He was regarded as a bandit, but in reality his exploits were more in keeping with those of a revolutionary.

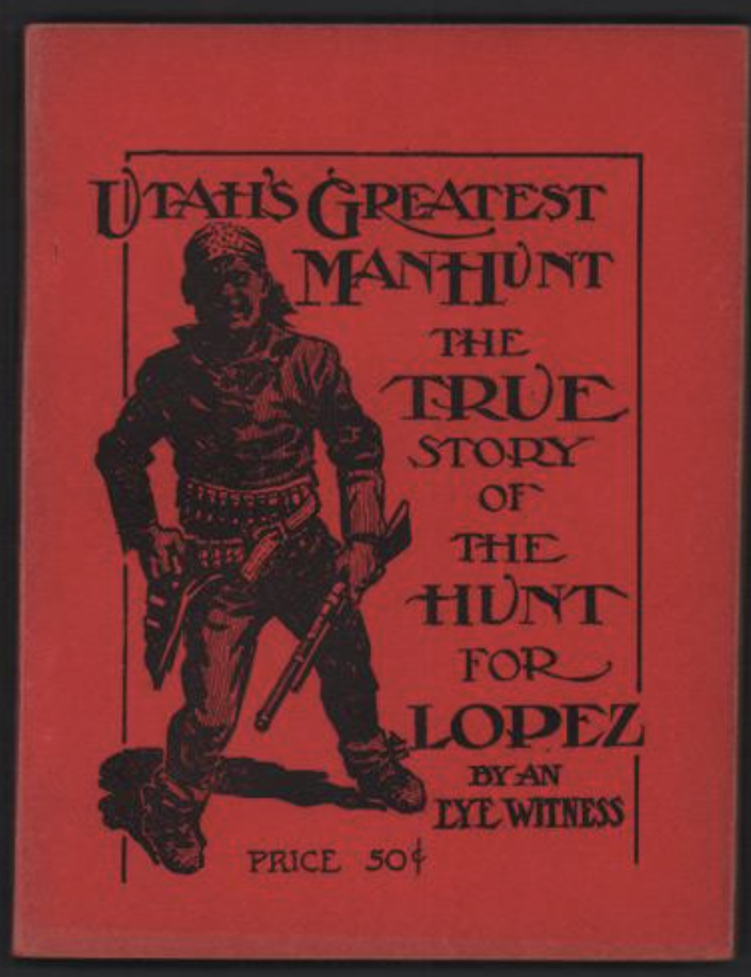

By the time the twentieth century rolled around, the term “bandit” was pretty much fixed in the minds of many White Americans as applying only to Mexican-origin people. And it was one that didn’t just allow for killing, it allowed for the massacring of large numbers of people, many of whom we know little about. Take Rafael Lopez, who became a “bandit” after being harassed by law enforcement in Utah, and who subsequently escaped to Texas, where he became Red Lopez. In 1921, Texas Ranger Frank Hamer received a tip that Lopez would be meeting with others so-called bandits. Hamer and a group of Rangers ambushed the men near the Rio Grande and killed a dozen or more people, all identified as bandits, in the attack.

There are actually quite a few examples where the Rangers killed a dozen or more people and simply excused themselves by labeling those people “bandits.” The Rangers clashed with a group of so-called “bandits” near Ebenoza in September of 1915 and captured and hanged a dozen or more men. The next month the Rangers found a dozen Mexican “bandits” dead outside of the small town of Lyford (some have speculated that they had killed these men and then “found them”). And then of course there was the Porvenir massacre. Ranger Captain James Fox reported after the massacre that his Rangers had killed 15 “bandits.” Other reports called the murdered residents of Porvenir “bandits,” “bandit gangs,” and “thieves, informers, spies, and murderers.” We know today (and they knew at the time) that the 15 men and boys executed that night were innocent.

The “bandit” label gave White authority and those in mobs a carte blanch reason as to how they could kill any Mexican person and get away with it. Hardly anyone who killed a person accused of banditry ever faced any kind of prosecution or punishment. The word “bandit” was a get out of jail free card for anyone who killed someone of Mexican ancestry. Perhaps reporter George Marvin explained it best in 1917 when he wrote, “the killing of Mexicans along the border in these last four years is almost incredible. Some Rangers have degenerated into common mankillers. There is no penalty for killing, no jury along the border would ever convict a White man for shooting a Mexican. Reading over Secret Service records makes you feel as though it was open gun season on Mexicans along the border.”[2]

George Marvin was right. He knew it 100 years ago, others did too, and we know it today. The common wisdom at the time, as I noted above, was that bandits were bad people. They were killers. They didn’t care about laws or rights or justice. So, who really were the bandits in this story?

[1] “US Soldiers Killed by Villistas,” Austin Statesman, December 3, 1917; “Troops Start Pursuit of Mexican Cattle Thieves,” Austin Statesman, December 29, 1917; “Infantry Awaits Bandit Attack on Indio Ranch,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, December 29, 1917; “Mexican Bandits Are Killed by Soldiers,” Galveston Daily News, December 31, 1917; “US Troops Kill 6 Mexican Bandits,” Fort Worth Record, December 31, 1917.

[2] George Marvin quoted in World Work Magazine January 1917, found in “1993/1994 INS/Customs/Border Patrol Complaints San Diego,” in American Friends Service Committee Papers, in Roberto Martinez Papers, Special Collections and Archives, University of California, San Diego.

Brian D. Behnken