As the bicentennial celebration for the Texas Rangers is on the horizon, audiences will witness the discussions on the folklore, myths, and violence play out in the media. Texas Monthly, for example, recently published several articles that highlight the legacy of the Ranger in Texas history. RTF founder Trinidad Gonzales wrote “Texas Rangers Bicentennial is a Time to Reflect Not Celebrate Mythology.” Texas Monthly also published a spotlight piece about the scholarship and experience of RTF’s Monica Muñoz Martinez on border violence. Both historians, as well as RTF member Benjamin Johnson, are interviewed for the podcast “White Hats” to explain the long history of anti-Mexican violence perpetrated by the Texas Rangers.

Those who downplay the history of violence often do so by arguing that “we”, should not place twenty-first century values on historical characters. Members of the Texas 1836 Project Commission utilized this argument several times in the most recent meeting in Austin. The people who want to uphold the Ranger myth want to put the history into “context” arguing “that’s just the way it was back then” and that it is “presentist” to assert otherwise.

But whose perspective does this privilege in the historical narrative? Ethnic Mexicans along the border had often shared stories within their communities and passed down the horrors of the generational trauma caused by Ranger violence. Let’s also understand that even in the 1910s, many border residents questioned the Ranger force and the interests that it served.

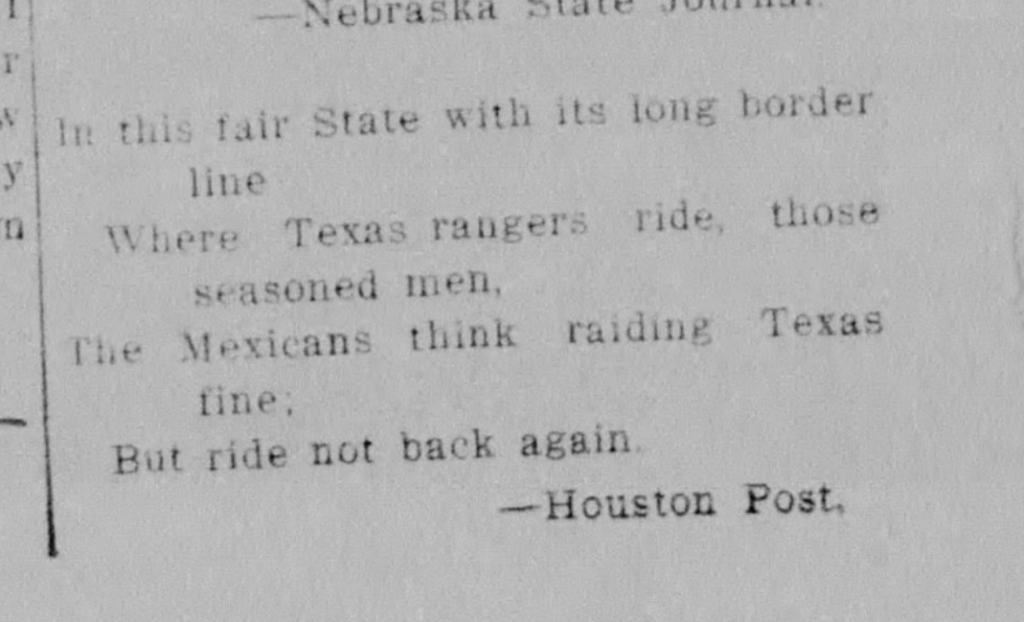

The poem above shows that journalists and readers were aware of Ranger violence, even if they approved of the tactics. The very foundation of the Texas Ranger myth is laid upon this knowledge. The public understood that if a Mexican, often described as a “bandit” to justify murder by the Texas Rangers, rode into Texas, or often on land they owned, it was more than possible that they would “ride not back again.”[1]

And yes, the same discussions about the purpose of the Texas Rangers and the violence they perpetrated on ethnic Mexicans and Mexican Americans found its way to the news media over one hundred years ago. Let that sink in…. Over one hundred years ago media outlets across Texas, such as the Laredo Weekly Times, asked “W-H-Y?”[2] Why the Texas Rangers? This question received quite a bit of traction in the legislative session of 1910, nine years before J.T. Canales called on the Texas Legislature to investigate the brutality of Ranger policing.

The majority of the publicity in 1910 came after two Greek men in Navasota were shot for not complying with Texas Ranger orders. These two Greek laborers, who happened to be riding in a buggy after the Navasota police received a complaint about a stolen buggy, failed to comply with order to halt, because they did not understand English. The Texas Rangers shot them onsite. The outcry was swift and prompted several news outlets to publish stories on the shooting and call on the Texas legislature to disband the Rangers. An article entitled “The Ranger Curse” appeared in the Austin-American Statesmen, which stated that even though the Texas Rangers may have once served a purpose, “with the passing of the Indian and the disappearance of the border ruffian, the necessity for this body of state officers of the law no longer exists…. which has now become a menace.” The author of the article called for the Texas Legislature to “check the absolutism” and the “acts of lawlessness” and the “constant reoccurrence of killings by the Rangers and raids by the Rangers.”[3] This writer knew about and applauded the violence by Rangers on the border as long as they targeted ethnic Mexicans and Native Americans, but once the two Greek men suffered the same fate, the newspapers publicly called out history of Ranger violence.

As Governor Oscar Colquitt took office in 1910, the government reduced the appropriation for the Rangers to the lowest levels in years. The discussion on both sides of the border called for the federal governments to be in charge of patrolling the region and not state sanctioned Rangers. Governor Colquitt disbanded one Ranger division from Austin in November 1910, cutting the companies from four to three.[4] By January 26, 1911, Governor Colquitt, in collaboration with Adjutant General Henry Hutchings, decided to cut that number even further back to two companies.[5] A political cartoon of Governor Colquitt also appeared in a local newspaper showing the governor calling the Texas Rangers “a foe to personal liberty.”[6] Whether or not this is what the governor believed is not certain, but a good deal of the public understood that the Rangers wielded too much power and used it unsparingly. People have been questioning the ethics of the Rangers and the need for them for more than a century.

But President William Taft did not agree as the Revolution began in Mexico. Governor Colquitt conferenced with President Taft in Hutchinson, Kansas, in 1911. There, Taft assured him that the federal government would compensate Texas for the expense of sending Rangers to the border. Governor Colquitt later requested that President Taft confer federal powers on the Rangers, instead sent federal troops to help. [7]

Many people residents of Laredo saw the Rangers as a force of violence rather than peace. As the Laredo WeeklyTimes asked, “W-H-Y?” Why are the Rangers here? The paper called it “the largest company of Rangers ever ordered to one place” where there was not a “disturbance in progress.” The author of the article concluded that the problems the Rangers were called in to solve were “invented.”[8]

In Laredo, many did not want the Texas Rangers in their backyards. Laredo did not have a permanent Ranger station in 1910. When the news spread that a company of Rangers lead by J. J. Sanders was headed to Laredo, the Laredo Weekly Times argued that “Webb County is in the 1300 mile stretch and has no Rangers…. And they are not needed nor desired.” Laredo leaders told the public that the local peace officers preserve peace along the Rio Grande “where two or three men at most are all that’s needed.”[9] Yet, the Rangers were told by the governor to stay in Laredo indefinitely.

By 1915, the Texas government planned a permanent substation for Laredo. Captain J.J. Sanders and Sargent W.T. Grimes, both of the new Company A, set up the station in the Heights- a section east of downtown and just north of the Texas- Mexico border. Under a reorganization plan, Governor James Ferguson increased the number of Texas Rangers, both the companies and membership. Company D, commanded by Henry Ransom, set up a station in Harlingen and patrolled from the Webb County line to Port Isabell.[10] Captain Sanders did the same from all of Webb County to Del Rio. Commander James Fox of Company B, which would later perpetrate the Porvenir Massacre, patrolled the Big Bend region from the headquarters in Marfa.[11]

Some of the most studied and well-known cases of violence happened at the hands of the Texas Rangers. For example, the ransacking of newspaper El Progresso in response to Jovita Idar not backing down to their violent threats, the murder of Jesus Bazan and Antonio Longoria, and the massacre of fifteen men and boys in Porvenir.

So, yes- let’s put the understanding of violence committed by the Texas Rangers into context. More than a century ago, ethnic Mexicans and their Anglo allies were deeply aware of the reputation of the Texas Rangers. They had to be; their lives depended on it. Present critiques of Ranger violence are not new. They are more than a century old and we should not forget that.

by Leah LaGrone

[1] Laredo Weekly Times , October 3, 1915.

[2] Laredo Weekly Times, November 12, 1911.

[3] “The Ranger Curse,” Austin American Statesman, July 10, 1910.

[4] “Possible Ranger Reduction”, Galveston Daily News, January 20, 1911.

[5] “Rangers Will Remain: Only Two Companies Instead of Three,” Austin American Statesman, January 26, 1911.

[6] Corpus Christi Caller-Times 27 Apr 1910, Wed · Page 4

[7] “US To Help Guard Texas Border,” The Topeka Daily Capital, September 27, 1911; “The Trouble on The Border,” The Houston Post, September 24, 1911; “Would Confer Federal Powers on Rangers,” Austin American Statesman, November 23, 1911; “Six Troop Trains reach Fort Worth on Way to Border,” Fort Worth Star Telegram, March 10, 1911.

[8] “Ranger Company Reaches Laredo,” Laredo Weekly Times, November 12, 1911.

[9] “Rangers Not Needed,” Laredo Weekly Times, February 12, 1911.

[10] “Ranger Company in Laredo Takes Station in Heights,” Laredo Weekly Times, August 1, 1915.

[11] “Little Interviews,” El Paso Herald, March 16, 1915.