“If one recognizes this vital urge that has engulfed the Negro community, one should readily understand why public demonstrations are taking place. The Negro has many pent up resentments and latent frustrations, and he must release them. So let him march; let him make prayer pilgrimages to the city hall; let him go on freedom rides -and try to understand why he must do so. If his repressed emotions are not released in nonviolent ways, they will seek expression through violence; this is not a threat but a fact of history.”

On a gloomy Saturday afternoon in January, the Duval County Historical Commission unveiled a historical marker commemorating the signing of El Plan de San Diego. A The declaration, written over a hundred years ago, called for a revolution against the United States to free the Southwest. This declaration was not the work of a fringe group of fanatics bent on anarchy, but rather was a cry against grievances left unanswered. For several years [1910-1920], the Texas Rangers and other forces such as American corporations and Anglo ranchers had levied a violent campaign against the South Texas Mexican communities for their lands and resources. Because of this, El Plan de San Diego was created as a call of action for people of the Southwest to take back their lands they believe were lost in the Mexican American War of 1846. This document asked for the banning together of Mexicans, African American, Native Americans and Japanese to fight back against the Texas Rangers. Although this revolt never really came to be, it did bring down the U.S. Army and increased the violence against the Mexican peoples in South Texas creating one of the bloodiest years, which would be known as the Matanza [massacre]. But this piece is not about El Plan de San Diego. It is about the triumph of the Mexican American spirit in a time of increased violence for being too brown and speaking Spanish.

For me, this event did more than commemorate an important document in San Diego, but instead highlights the importance of South Texas history, Texas History and U.S. History. It spoke to the pain of a community that has seen its fair share of violence by Texas Rangers and others. It was more of a triumph of resistance and a dedication to having their people’s history told. When I first arrived at a renovated lumber store turned church where the ceremony was to be held, I was approached by an elderly woman who had seen me speak at the De Los Parás memorial back in October. Her name is Lidia Oliveira Canales, and she is the 94-year-old granddaughter of one of the men slaughtered by the Texas Rangers on April 1, 1920. She pulled me aside and told me she had received a threatening phone call a few days later from someone representing the Texas Rangers asking her to recant her story. She answered that she would not, that this was her grandfather’s story, and she believed the community. A short while later, a man came to her house to make the same threat, but she shut the door in his face.

For too long our community has been intimidated by the Texas Rangers and by law enforcement and on that day one Mexican American woman stood up to say, “No more.” This is the triumph of the spirit of the Mexican American community. It was January 28th when we gathered to unveil the historical marker and the county judge read a proclamation declaring the historical marker of El Plan de San Diego. This day held more history than the commemoration of a historical marker. It was also the 108th anniversary of the Porvenir Massacre where 15 men and boys were slaughtered by Texas Rangers and others outside of El Paso, Texas, yet another grim reminder of the violent history that plagues the region to this day. It was a day to speak of violence against people of color in this country. It was a day to speak of the failures of law enforcement to save 21 people from being gunned down at Robb Elementary in Uvalde, Texas not even a year ago. It was a day to speak of a shooter killing 23 people in a Wal-Mart in El Paso, Texas by a man looking to kill Mexicans and Mexican Americans. This day was about remembering all of that because memory is the most powerful tool of the oppressed.

“The memory of oppressed people is one thing that cannot be taken away, and for such people, with such memories, revolt is always an inch below the surface.”

In retrospect, El Plan de San Diego, offers more speculation than answers. Who started it? Where was it actually written? Who was behind it? Carranza? The Germans? Possibly anybody but a group of educated Mexican Americans who were upset by the violence reigned down on them for too long. The truth of the matter is that those answers are inconsequential and do not offer insight to the true significance of the proclamation itself. Whether this document was a good idea or not, it is a triumph of the spirit of Mexican Americans to stand against unsurmountable odds and speak for the oppressed in this country. This is the lasting legacy of El Plan de San Diego, whether you agree with their actions or not, it is simply that. A document that speaks of the liberation of oppressed peoples in this country and for that it should go down in history with the efforts of John Brown and other rebels who fought to free a people.

By Christopher Carmona

El Corrido de los Secidiosos

Composer unknown

Ya la mecha esta encendida

Por los puros mexicanos,

Y los que van a pagarla

Son los mexicotejanos.

Ya la mecha esta encendida

con azul y colorado,

Y los que van a pagarla

Van a ser los de este lado.

Ya la mecha esta encendida,

muy bonita y colorada,

Ya la vamos a pagar

los que no debemos nada.

Y se van los sediciosos

ya se van de retirada,

De recuredos no dejaron

una veta colorada.

Ya se van los sediciosos

y quedaron de volver

Pero no dijeron cuando

porque no podian saber.

Despedida no la doy

porque no la traigo aqui,

Se la llevo Luis de la Rosa,

para San Luis Potosi.

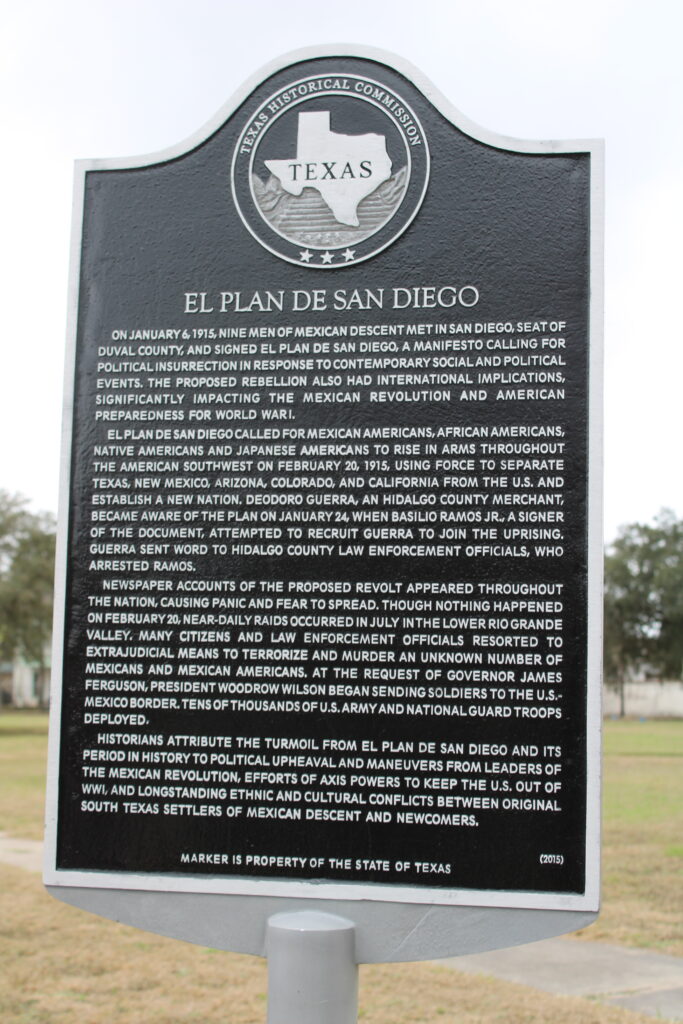

The Historical Marker Inscription:

On January 6, 1915, nine men of Mexican descent met in San Diego, seat of Duval County, and signed El Plan de San Diego, a manifesto calling for political insurrection in response to contemporary social and political events. The proposed rebellion also had international implications, significantly impacting the Mexican Revolution and American preparedness for World War I. El Plan de San Diego called for Mexican Americans, African Americans, Native Americans and Japanese Americans to rise in arms throughout the American Southwest on February 20, 1915, using force to separate Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and California from the U.S. and establish a new nation.

Deodoro Guerra, a Hidalgo County merchant, became aware of the plan on January 24, when Basilio Ramos Jr., a signer of the document, attempted to recruit Guerra to join the uprising. Guerra sent word to Hidalgo County law enforcement officials, who arrested Ramos. Newspaper accounts of the proposed revolt appeared throughout the nation, causing panic and fear to spread. Though nothing happened on February 20, near-daily raids occurred in July in the lower Rio Grande Valley. Many citizens and law enforcement officials resorted to extrajudicial means to terrorize and murder an undetermined number of Mexicans and Mexican Americans. At the request of Governor James Ferguson, President Woodrow Wilson began sending soldiers to the U.S.-Mexico border. Tens of thousands of U.S. Army and National Guard troops deployed.

Historians attribute the turmoil from El Plan de San Diego and its period in history to political upheaval and maneuvers from leaders of the Mexican Revolution, efforts of axis powers to keep the U.S. out of WWI, and longstanding ethnic and cultural conflicts between original South Texas settlers of Mexican descent and newcomers.