#OTD on February 10, 1919, the ninth day of the Joint Committee of the Senate and the House in the Investigation of the Texas State Ranger Force (hereafter, “Canales Hearings”) took place in the Texas state capitol.

The first matter taken up was a procedural issue, but one that had enduring consequences. The House voted to not print the transcript of the hearings in the daily journals of the House and Senate. Ranger leaders supported this measure, saying that surely the transcripts would be printed once the hearings were completed. But they never were, with the few copies of the enormous transcript remaining inaccessible to the public and most scholars for generations.

The exception, as historian Jim Sandos explains, was historian Walter Prescott Webb, whose 1935 book The Texas Rangers is a hugely influential defense of the Rangers and a celebration of their violence against Indians and ethnic Mexicans. https://utpress.utexas.edu/9781477322680/

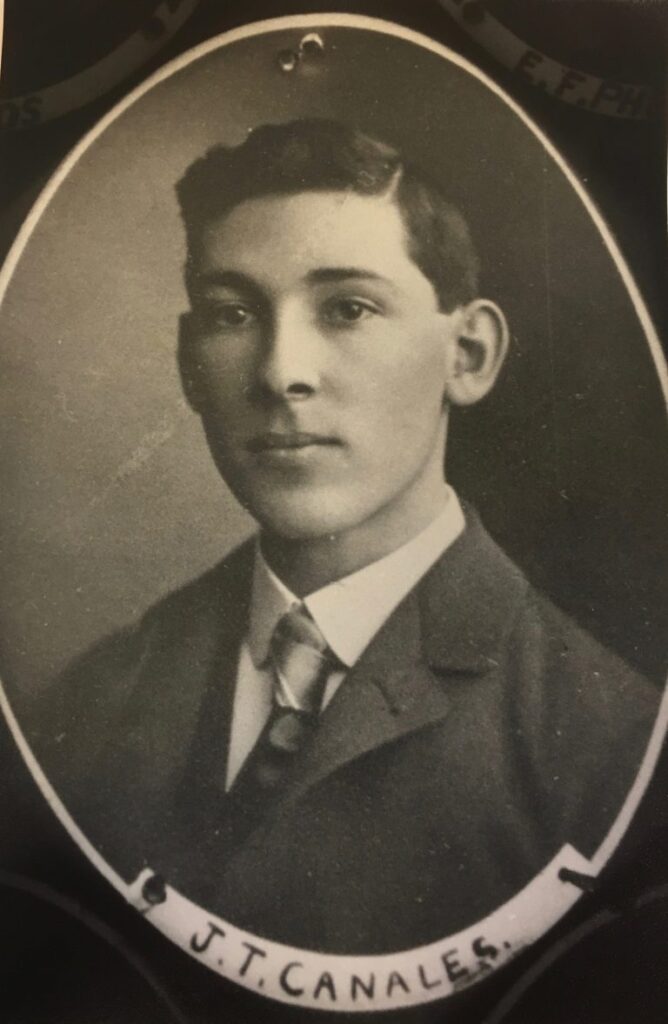

Most of the rest of the day was occupied by the testimony of JT Canales himself. He would describe the worse of the anti-Mexican violence in great detail. He also found himself on trial, with his motives and loyalty as an American impugned.

The hearing room was standing-room only, with crowds spilling into the hall and standing outside the windows. The House had voted down a measure that would have moved the proceedings into its much larger chambers.

Canales began by invoking his family’s long history in the borderlands, including his past cooperation with Rangers “whose own conscience was self-restraint and law.” The recent troubles came from Ranger violence, especially by Captain Henry Ransom.

After Rangers removed Rodolfo Muñoz from a San Benito jail and allowed a mob to shoot and hang him, Mexican Americans stopped believing “that the officers of the law would give them the protection guaranteed to them by the Constitution.”

Canales went so far as to defend Aniceto Pizaña, one of the leaders of the Plan de San Diego uprising, as having been pushed into violence by an attack on his ranch orchestrated by an Anglo neighbor who coveted his land.

He was also at pains to stress his own loyalty, emphasizing his role in having scouts assist the U.S. army in suppressing raids by Pizaña and his allies, and his efforts in supporting the U.S. effort in World War I.

Canales described at length his efforts to work behind the scenes for the reform of the Rangers and dismissal of violent officers, and how he felt forced to go public when governor Hobby did not act and Ranger Frank Hamer threatened him and stalked him.

In the afternoon, Robert E. Lee Knight cross-examined Canales. Knight continually attacked Canales’ mental stability. “Now isn’t it a fact, Mr. Canales, that you have become obsessed in a way with suspicion and hallucination regarding the seriousness of this [Hamer] matter?”

Knight also implied that victims of Ranger violence were guilty and thus deserved their treatment. He demanded a list of innocent men murdered by Rangers. Canales replied that all those killed were legally innocent since they had not been tried and found guilty.

Knight’s logic justified extrajudicial killings and prompted a rebuke from committee members and chair Bledsoe, who observed that “under the laws of the state, they are presumed to be innocent until their guilt is proven.”

Knight also pressed hard to place Canales into the maelstrom of Texas politics, particularly the rivalry between then governor William Hobby and his predecessor, James Ferguson. Knight repeatedly implied that Canales turned on the Rangers not out of principle but rather expediency.

Knight went further, asking Canales if “you are by blood a Mexican?” Canales responded “I am not a Mexican, I am an American citizen,” thereby emphasizing national identity over race. Knight would have none of it. “By blood?” Knight followed.

“There is a saying that blood is thicker than water,” Knight told the crowds, and pointed to distant relatives of Canales who had escaped the draft by fleeing to Mexico, which Knight said surely influenced Canales “unconsciously.”

Ranger defenders continued this onslaught with the testimony of the next witness, Claude Hudspeth, a U.S. representative, former Texas legislator, and leading advocate of a full U.S. intervention into Mexico to check the course of the Mexican Revolution. /https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/hudspeth-claude-benton

Rather than dispute Ranger and other violence, Hudspeth justified them. He represented the border as a violent and threatening place to Anglo residents. “Bandits” from Mexico were supported by Mexican American residents and their “information network.”

This supposed persistent threat justified state violence against ethnic Mexicans. As he said, “Mexicans at El Porvenir were killed by Rangers and good citizens of that section that were searching for their property.”

Mob law for Hudspeth was a necessary and noble endeavor that protected the lives and property of white borderlands residents. “If I had it in my power I would lead a mob in a minute” against “bandits,” he said. “I will come back from Washington to lead them if I am needed.”

In case his comments left any doubt about whether racial violence was justified, Hudspeth added that “You have got to kill those Mexicans when you find them, or they will kill you.”

In sum, the days’ testimony revealed the contours of the debate over Canales’ proposed reforms: there was no doubt that the Rangers and vigilantes inspired and emboldened by their brutality had committed outrages.

But there was no willingness in the legislature to question the racism or the ideology and practice of mob violence that justified such attacks. Canales, the only non-Anglo legislator, brought irrefutable evidence of Ranger violence, but he was swimming against strong tides.

This thread is a part of the #OTD in Ranger history campaign that @Refusing2Forget is running this year. Follow this twitter handle or https://refusingtoforget.org/ranger-bicentennial-project/, and visit our website https://refusingtoforget.org/otd-calendar/ to learn more.

Key secondary sources for this thread include:

@BenjaminHJohns1’s Revolution in Texas (pp 169-175)

@MonicaMnzMtz’s The Injustice Never Leaves You (182-216)

Reverberations of Racial Violence

and Ribb, “Reader’s Guide to the Canales Hearings”

A more detailed thread on February 10’s hearings can be found on the centennial “live” tweet of the investigation: https://twitter.com/1919TXRangerInv