On July 23 or 24, 1915, the brothers Lorenzo and Gorgonio Manríquez were killed near Mercedes, Texas, by deputy sheriffs, in a chain of events that unleashed violence across south Texas in late summer and fall of 1915.

The double murder and subsequent events reveal many of the dynamics that made 1915 so violent: wrenching economic change, an insurrection that targeted Anglos and some Tejanos, plus vigilantes and state agents, including Rangers, who worked together.

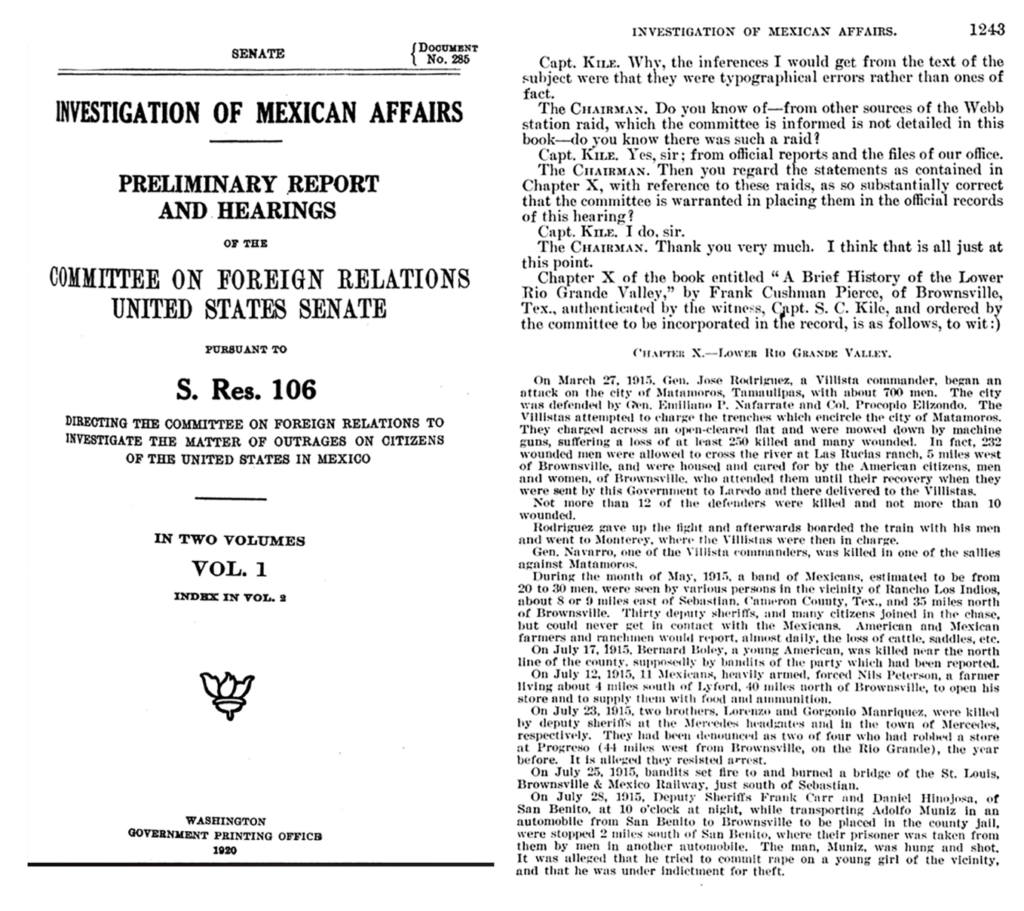

Hidalgo County sheriff Stokes Chaddick and US Customs inspector John White shot the brothers. According to Brownsville attorney and historian Frank C. Pierce, Lorenzo died near the headgate of the Mercedes Canal, and Gorgonio fell in Mercedes itself.

UTRGV Archives: Frank Cushman Pierce (1858–1918)

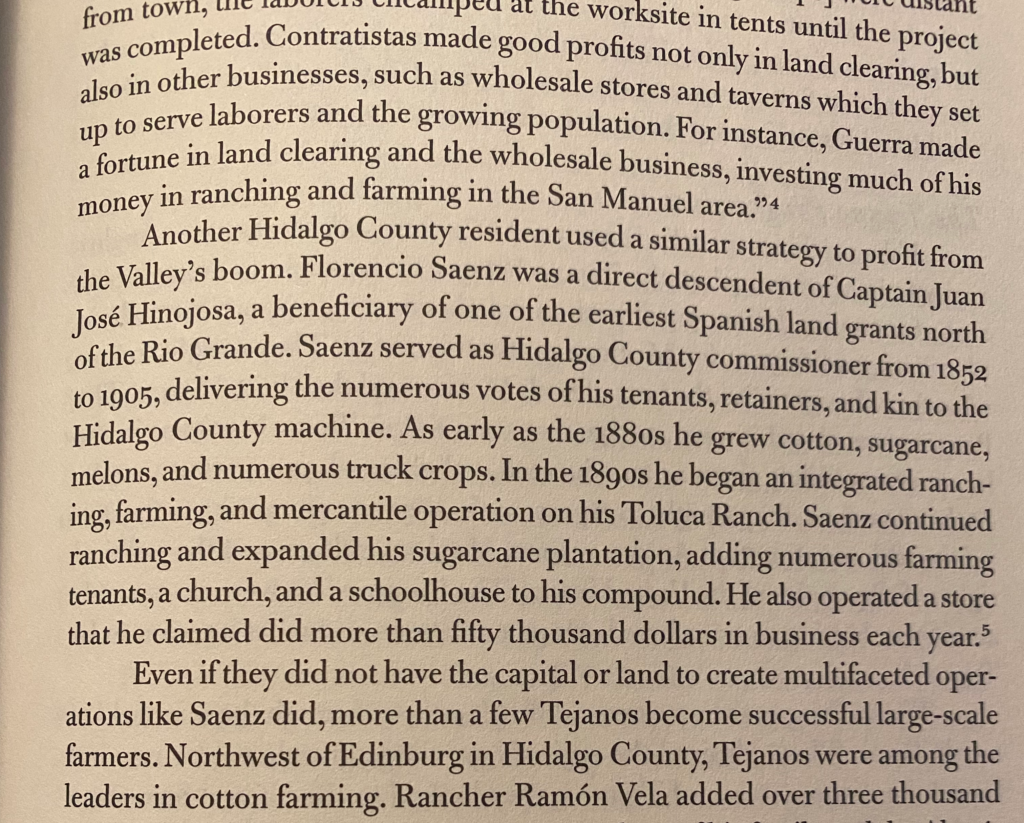

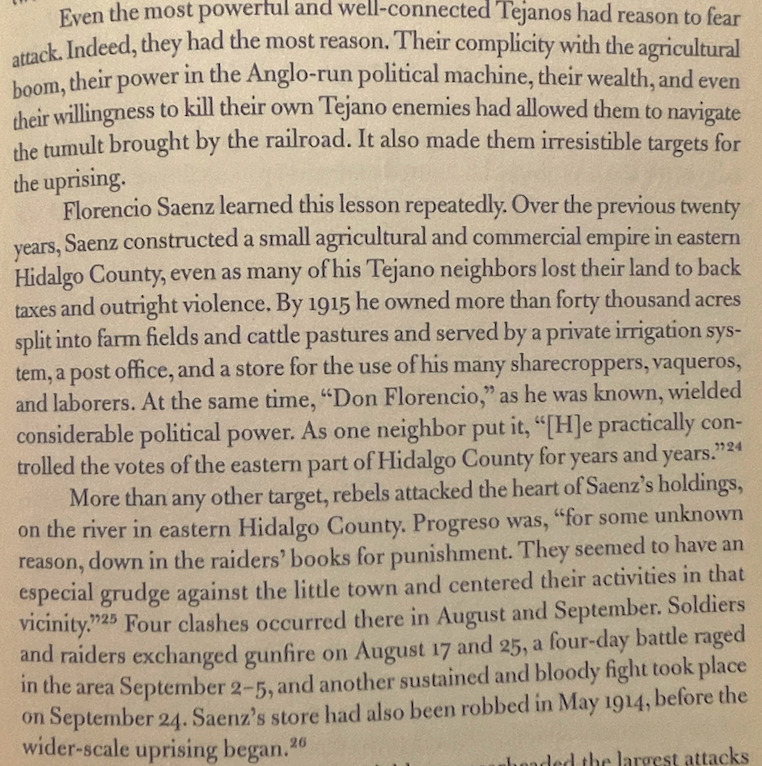

Pierce reported that Florencio Saenz, a major land developer and labor contractor in nearby Progreso, had reported the brothers as being participants in a raid on his store in May of 1914.

Saenz is a good example of the small but important class of Tejano landowners who cooperated with Anglos in bringing irrigation agriculture and rail lines to the region, and marketing it to white farmers in the Midwest.

Because this influx led so many Tejano landowners to lose their land to delinquent tax payments and sometimes outright fraud and violence, Saenz was targeted by insurrectionists four times in the two months following the Manriquez’s deaths.

These raids took place amidst the greatest successes of the Plan de San Diego revolt, when rebels destroyed infrastructure and stage daring attacks on prominent farms and ranches, bringing terror to farm and ranching families.

Although stereotypes of Mexicans as inherently violent and criminal played a critical role in justifying anti-Mexican violence in the 1910s, we should not overlook the roles of property and labor, which help explain why Tejanos were both insurrectionists and their targets.

Sheriff Chaddick and his colleagues claimed that the Manriquez brothers were shot because they resisted arrest. This was one of the first times in 1915 this excuse was used to justify death at the hands of law enforcement officers. It would not be the last.

Pierce, disturbed by what seemed to him to be an illegal execution, began making a list of such victims. Only four days later, on July 28, he added another name, Adolfo Muñiz [sometimes ‘Muñoz’], killed after being taken into Ranger custody.

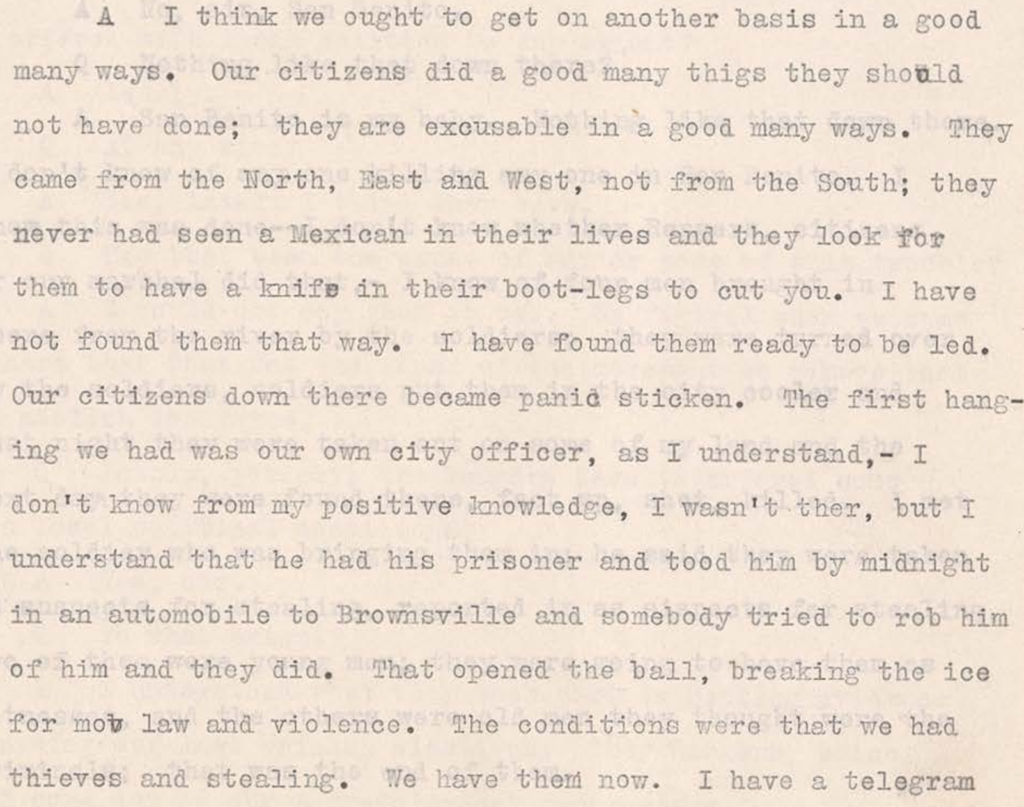

Many Tejanos concluded that to be arrested was to risk summary death at the hands of law enforcement; at the same time, the lack of any investigation of Chaddick, White, or the Rangers broke “the ice for mob law and violence.”

Information for this thread comes from Revolution in Texas and from https://www.lynchingintexas.org hosted by @SamHoustonState.

This thread is a part of the #OTD in Ranger history campaign that @Refusing2Forget is running this year. Follow this twitter handle or https://refusingtoforget.org/ranger-bicentennial-project/, and visit our website https://refusingtoforget.org to learn more.

Refusing to Forget members are @ccarmonawriter @carmona2208 @acerift @soniahistoria @BenjaminHJohns1

@LeahLochoa @MonicaMnzMtz and @Alacranita, another co-founder is @GonzalesT956.

@emmpask @sdcroll @HistoryBrian @LorienTinuviel @hangryhistorian, @ddsanchez432,

@elprofeml, and @littlejohnjeff are other scholars working on this project.