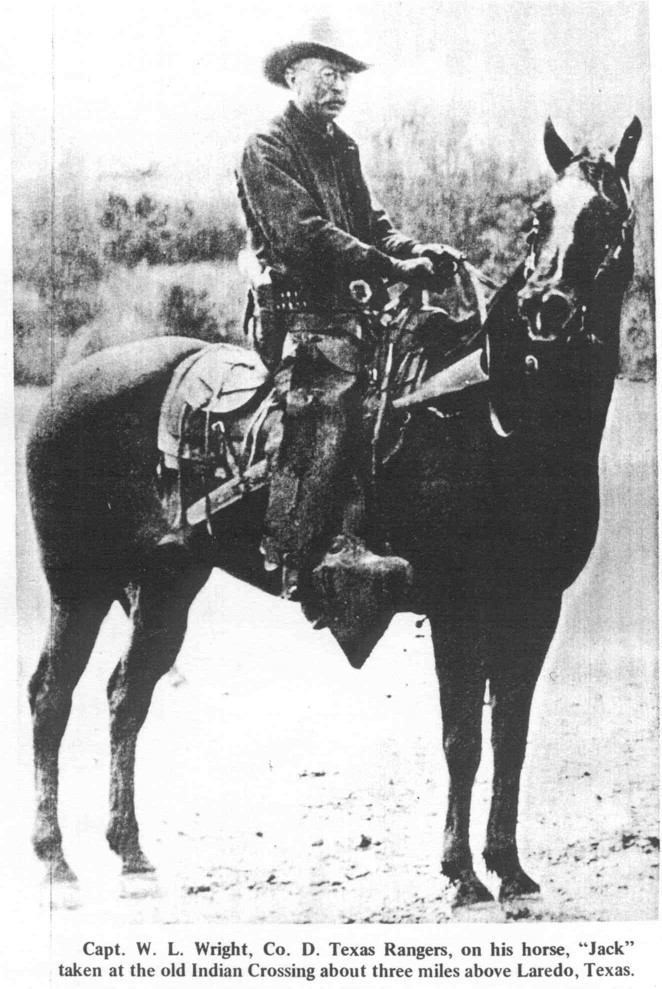

December 18, 1922, a century ago today, Texas Rangers and mounted U.S. Customs officers policing the border killed a group of suspected mounted liquor smugglers in Zapata County. Rather than engage the suspects in the open, or make an arrest and put the men on trial for violating Prohibition, Texas Ranger Captain William L. Wright prepared an ambush. As he informed historian Walter Prescott Webb, officers trailed the suspects, then got ahead of them and laid in wait. Webb recorded that Wright, “planned his attack so as to cut off… retreat,” and positioned officers to “flush the game,” into law enforcement’s crossfire.[2]

Wright’s attack succeeded in killing three “Mexicans” and recovering a quantity of contraband liquor intended for the “Christmas trade.” [3] Local accounts provide a different view of this ambush. The corrido[Mexican folk ballad] Los Tequileros gives names to the victims who died that day. In the corrido, two professional tequileros, Gerónimo and Silvano, cross the Rio Grande into Texas and decide they need the assistance of another man who they add to their party. Leandro initially refused, claiming illness. According to local history, Leandro was not a professional smuggler like the other men, but a young man who had never smuggled before or otherwise broken the law.[4] Leandro, like most rural Tejanos, had only a few years of elementary education. He made some money from a little billiard hall he operated across the river in Guerrero, Tamaulipas, but not enough, apparently. Times had been hard for Leandro since his wife died, and the money he could make working with Gerónimo and Silvano would help raise his three children. What Gerónimo and Silvano told Leandro to coax him out of his sick bed is unknown, but leave it he did. When the trio came across the rinches, as ethnic Mexicans commonly called murderous American law enforcement, he was the first to fall.[5] Leandro Villarreal’s story shows that tequileros were more than the armed brigands that U.S. law enforcement portrayed them to be. Some were merely young men from rural backgrounds trying to get by.[6]

In the aftermath of the Plan de San Diego, American law enforcement in South Texas viewed tequileros with a greater wariness. Texas Ranger Captain William W. Sterling put it simply; tequileros “had to be dealt with as foreign enemies, not as ordinary domestic bootleggers.”[7] Some tequileros of the Prohibition era may have been former sediciosos, but even if they were not, they knew to fear the rinches who killed so many ethnic Mexicans the decade before. Given the nature of state tactics, it is not surprising that the balladeer in the corrido Los Tequileros comments that the only way the rinches can “kill us is by hunting us like deer.”[8] Knowing the danger, tequileros armed themselves and resisted apprehension with force because they likely felt it was the only way to save their lives.

Decades after his death at the hands of U.S. law enforcement, family members disinterred Leandro from the unhallowed grave where Texas Rangers had left him. Rather than rebury him quietly, family members took pride in the legend that Leandro became after his death. On November 10, 2000, family members and locals celebrated Leandro’s life in a memorial mass held at Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church in Zapata. Not only did information regarding Leandro’s role in Los Tequileros appear in newspaper coverage of the event, but family members chose to forever embrace Leandro’s past as a tequilero by literally chiseling it in the stone above his grave (using the incorrect date for his death from the song). The fact that the artisan who completed the headstone took no pay for his labor, but provided the monument at cost makes clear Leandro’s reverence beyond his family and the ethnic Mexican community’s refusal to forget.[9]

by George T. Díaz

[1] Portions of this post are taken from Border Contraband. George T. Díaz, Border Contraband: A History of Smuggling across the Rio Grande (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2015).

[2] Walter Prescott Webb, The Texas Rangers: A Century of Frontier Defense(Austin: University of Texas Press, 1965), 556.

[3] Ibid.

[4] According to his baptismal record, Leandro Villarreal was born February 27, 1895, making him twenty-seven years old at the time of his death. Certificate of Baptism, Our Lady of Refuge Catholic Church, Roma, TX.

[5] Rinche is a highly derogatory term for an American law enforcement agent. For more on rinches see Américo Paredes, With His Pistol in His Hand: A Border Ballad and Its Hero (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1958), 24.

[6] Paredes, A Texas-Mexican Cancionero: Folksongs of the Lower Border (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1976),81.

[7] William Warren Sterling, The Trails and Trials of a Texas Ranger (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1959),84.

[8] Paredes, A Texas-Mexican Cancionero, 101.

[9] “Memorial Mass,” Zapata County News, 2 November 2000.