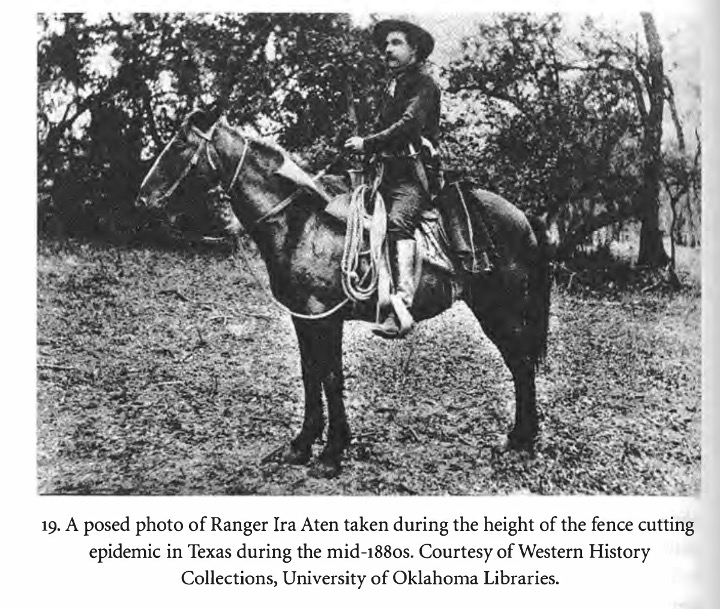

In the summer of 1888, Texas Rangers Ira Aten and Jim King went undercover to try to identify and arrest so-called “fence cutters.” They were unsuccessful. In frustration, Aten developed a plan to hide mines in the fences, blowing them up when cutters approach.

To understand how military equipment, like mines, could be introduced into local property conflicts in Texas in the 19th century, one must look to the longer history of what have come to be known as the “Fence-Cutting Wars.”

These conflicts emerged out of a shift in the property regime, primarily because of the Homestead Act of 1862, which made it increasingly possible to claim and delineate private property for some, and not others.

Some of the property being articulated through legal means in the 1862 Act had been recently settled by primarily White – Anglo newcomers to Texas and helped them accelerate their legal claims, in the U.S. framework, to this stolen land.

Prior to this period, agreements had been made between property owners and ranchers and cowboys such that a broader group of people could move their animals across the land, or openly graze their livestock, regardless of ownership.

With the invention of barbed wire, in 1874, property owners began to use the technology to fence off their property, limiting the range of motion for those who depended on communal property agreements to take care of their livestock.

For many, their livelihood depended on these prior agreements. As quickly as property owners mounted these fences, they also started to notice that their fences were being cut to maintain the use of old grazing pathways.

Powerful property owners, sometimes called Cattle Kings, held sway in Texan government and asked for greater protection against this “nuisance”.

By 1883, the Texan government was being lobbied by powerful ranchers, like from King Ranch, to call in the Texas Rangers to deal with the fence-cutters, and in 1884 it passed new fence-cutting legislation.

Andrew Graybill writes in Policing the Plains that with this “Austin had demonstrated its resolve to protect private property and to defend an industry of unquestioned economic value to the state.” (140).

The Texas Rangers, as a policing force that could be manipulated by a few for the benefit of a few, was charged with eradicating fence destruction across the state, in part because local police were either ambivalent on the issue, or even supported fence cutters.

Even as Texas Rangers attempted to apprehend fence cutters, it was difficult for them to secure jail time for cutting wires. Legislation from Austin was not being applied evenly.

This did not stop the Rangers from intimidating fence-cutters by other means. For example, they are documented as violently ambushing fence cutters on G.B. Greer’s land during this time, killing one.

By 1886, the Rangers campaign was still not particularly effective. Even so, King Ranch, which had been paying for protection by hiring private detectives to find individual perpetrators, revived its undercover operations but now with the help of the Rangers.

The Texas Rangers were asked to serve as infiltrators into the lives of primarily property-less ranchers. Rangers with Company F, including Ira Aten, were documented as ambushing fence cutters in Brownwood, Texas. Two men were killed in this operation.

It is unclear if there was a “battle” between the Rangers and the fence cutters, or if the fence-cutters, here named Amos Roberts and Jim Lovell, were shot as they ran away.

And so we return to the year 1888, when Ira Aten attempted to introduce mines into these operations. Given this background, it would be difficult to read this as anything other than upping-the-ante in a failing mission to protect the property of powerful land-owners.

The militarized strategy was quite quickly reeled in by the governor.

The “fence-cutting wars” continued, albeit in different forms, until the implementation of the Taylor Grazing Act 1932. But the 1880s had solidified the policing of Texas’ private property regime both materially and culturally in Texas.

The “fence-cutting wars” can also be understood as historically a part of the “Range Wars” of the Southwest more broadly, which situates them as the ongoing project of settling land by way of often brutally violent means.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Range_war

The Texas Rangers were enlisted to protect the powerful and the wealthy in Texas from ordinary people, creating not the landscape of the self-made man, but of an economic elite.

This thread is a part of the #OTD in Ranger history campaign that @Refusing2Forget is running this year.

Follow this twitter handle or https://refusingtoforget.org/ranger-bicentennial-project/, and visit our website https://refusingtoforget.org to learn more.

Refusing to Forget members are @ccarmonawriter @carmona2208 @acerift @soniahistoria @BenjaminHJohns1 @LeahLochoa @MonicaMnzMtz and @Alacranita, another co-founder is @GonzalesT956

.@emmpask @sdcroll @HistoryBrian @LorienTinuviel @hangryhistorian, @ddsanchez432,

@elprofeml, and @littlejohnjeff are other scholars working on this project.