By John Mckiernan-Gozález

“In 2017, like in 1919, there seems to be a broad gulf between minority communities’ faith in the law and the law’s acknowledgments of their presence in Texas.”

McKiernan-González is a history professor at Texas State University and author of Fevered Measures: Public Health and Race at the Texas-Mexico Border, 1848-1942

Evidence of violence can be found in some of the more beautiful places in Texas. One of the best research collections for Texas history resides on the slim sand bar separating Oso from Corpus Christi Bay, less than a kilometer from the Gulf of Mexico. In addition to holding the papers for Dr. Hector Garcia, one of the founders of the GI Forum, the special collections at the Mary and Jeff Bell library at Texas A & M University – Corpus Christi also hold the personal and professional papers for Dr. Clotilde Garcia, one of the first Latinas to be licensed as a physician in Texas (1954). A World War II divorcee, Clotilde Garcia raised her son Jose Antonio Canales while running an elementary school and then attending UT Medical Branch Galveston, becoming the first Mexican American woman to graduate from a public medical school in Texas. Dr. Cleo, as she was known by her patients and her colleagues, kept a thriving practice deep in the heart of working class Mexican American Corpus Christi. Dr. Cleo also maintained an ongoing engagement with the democratic institutions that challenged Jim Crow in Texas, going from chairing the medical affairs committee for LULAC in the 1960s to being a delegate at the Texas Constitutional assembly in the 1970s. Dr. Cleo’s papers held an interest for anyone in the politics of health under Jim Crow, let alone my interest in Mexican Americans in Texas.

Turns out, however, Dr. Cleo was also a Texas historian. Once her son graduated from law school, Dr. Cleo pursued her interest in early Texas History. She published articles in theSouthwestern Historical Quarterly on key events in Spanish Texas, eventually building an impressive database of families in Texas, Nuevo Leon, and Tamaulipas connected to the Garza Falcon land grant. Her research efforts linked violent military conflicts to the settlement of Texas, seeking to place her people in the origin myths and public memory of Texas.[1] Writing and working on early Spanish land grants during a time of increased drilling in South Texas, Dr. Cleotilde must have been aware of the commercial and political impact of land claims on the status of Mexican American communities across South Texas. History – the broad connection between past and present – clearly mattered, and evidence of this importance lay strewn throughout the collection.

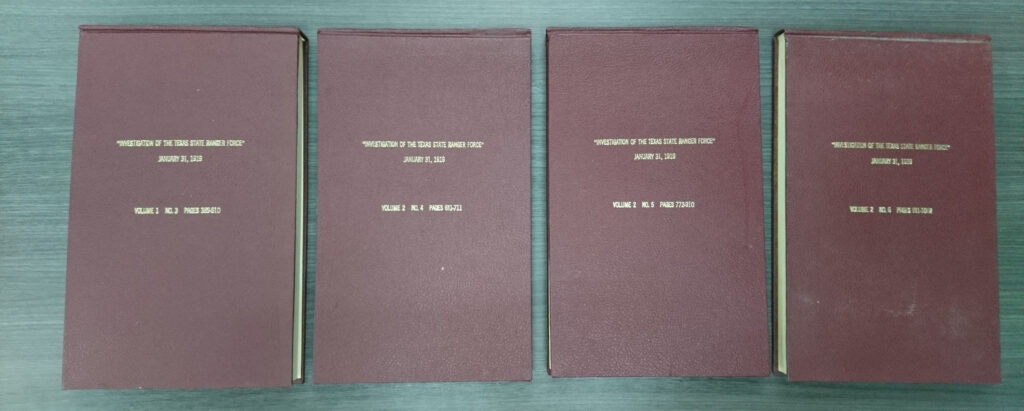

This is where I found Dr. Cleo’s book of horrors: The Transcript of Proceedings of the Joint Committee to investigate the Texas Rangers, 1919.[2] I first saw this book behind a glass case at the exhibit Life and Death on the Texas Mexico Border, 1910-1920, an exhibit that marked the importance of state violence in the museum that holds “The Story of Texas.”[3] I had read about this collection of testimony in Benjamin Johnson’s book, Revolution in Texas. I read excerpts from survivors of Texas Rangers giving this testimony in David Montejano’s Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas. In college, I learned about South Texas from Julian Samora and Judge Albert Peña’s Gunpowder Justice: a Reassessment of the Texas Rangers,which used this book as a basis for their discussion of the Texas Rangers.[4] These scholars discussed the horror of having this key book buried in the Texas State Library and archives, ‘hidden’ from public access and only available in Austin. I know about this book because of a professional obsession with the Mexican Revolution. This book carried the ‘death’ portion of the Refusing to Forget exhibit at the Bob Bullock museum within its bound and – at the exhibit – inaccessible pages.

Dr. Cleo’s research collection gives the lie to this assertion. The book and the testimony is available to the public, if the public can afford to go to Corpus Christi and have the time to sit down with pencil and archive- provided paper to peruse the book, between 9-5 from Monday to Friday. Dr. Cleo maintained an interest in the impact of violence on Mexican settlement in Texas. In this case, her personal effects included the state archive of violence against Mexicans in the broader community where she and her family settled, once in the 1720s and again during the Mexican Revolution. Dr. Cleo’s work focused on family presence during drastic changes in land tenure – a fancy word for loss of land to people with more guns and political power. I do not know how Dr. Cleo acquired this bound volume. I do not know if she kept the books with her when she talked with her patients or did her research and writing on the history of early Texas. What is true is that I was able to touch the papers that gave evidence to the faith some people in South Texas placed in the American legal system, endangering themselves and their families to bear witness against the violence Texas state agents wrought against people they deemed too Mexican to be American.

In 1919, people tramped to the capitol. They took trains to the capitol. They talked to investigators in South Texas. They took their lives in their own hands to participate in American legal proceedings. They even elected the lawyer J.T. Canales to represent their interests, and their representative faced gunfire upon entering the doors of the Capitol.[5] The bound legislative proceedings provided material testimony to a broad community’s commitment to the possibilities of the rule of law.

In the last eighteen months, I have been privy to two broad pilgrimages to the Texas capitol. The first happened in early 2016. My students made their way to the Bob Bullock Museum to see Life and Death on the Texas Mexico Border. For the price of entrance (or free on the third Sunday), students saw a public accounting of the violence wrought on Mexican bodies by agents of the state of Texas. They saw the clothes and material culture people like them created at the turn of the century. They saw people that looked like themselves in the history of Texas. The exhibit gave them a place where Mexican American experiences were the protagonists in “The Story of Texas” (as the museum bills its exhibits). They discussed situations and hostilities that may or may not have had parallels in their lives and their immediate histories. They saw a public accounting of the effects of excluding Mexicans from the twentieth century history of Texas. And – at the end of the exhibit – they saw the book of horrors: the Legislative Proceedings of the Investigation of the Texas Rangers.

The second involved senate hearings regarding State Bill Four. This pilgrimage was set into motion by Travis County Sally Hernandez’ public discussion of the impact of ICE detainers on the county’s relationship to migrant communities. Or, more precisely, Governor Abbot’s anger that a Mexican American female sheriff and a female college president might have a different understanding of their legal obligations to their constituents and their communities set into motion a series of events that brought large numbers of immigrants and their community advocates to the state capitol. Like in 1919, many of these witnesses put their legal status at risk to give testimony. As Jonathan Turlove noted, Governor Abbot used SB4 to “Hammer Travis county,” turning Texas from a place that co-existed with its southern neighbors to becoming the leading edge of anti-immigrant politics.[6] They took to the microphones of the legislature to help Texans of all stripes realize the migrant presence in their lives, to see the ways in which Texas is bound up with Mexicans, Latinos, Asians and their neighbors.

The legislative impact of the overwhelming testimony seems to be temporarily irrelevant. However, the air of threat has not dissipated since these hearing in the late spring of 2017. One representative threatened “to put a bullet in the head” of another representative because he feared the presence of a veteran and the echoes of undocumented immigrant advocacy.[7]The head of ICE told immigrant communities “they should be very concerned.”[8] And, as John Burnett ably put it in his ride-along with ICE in Dallas, ICE spent “most of their time drinking coffee waiting in working-class Hispanic barrios.” In 2017, like in 1919, there seems to be a broad gulf between minority communities’ faith in the law and the law’s acknowledgement of their presence in Texas.[9] There is a grim beauty in the Story of Texas.

[1] Clotilde P. Garcia, The Siege of Camargo, (Austin: San Felipe Press, 1975); Clotilde P. Garcia, Captain Jose Maria Garza Falcon: Colonizer of South Texas, (Austin, TX: San Felipe Press, 1982); Clotilde P. Garcia, Padre Island and Padre Jose Balli: Application for a Historical Marker, (Corpus Christi, TX: Grunwald Press, 1979)

[2] “Investigation of The Texas Rangers, 1919 V. I and V. II.” Box 22, Cleotilde Garcia Collection, Special Collections, Mary and Jeff Bell Library, Texas A&M University – Corpus Christi.

[3] Bob Bullock Texas State Museum of History, https://www.thestoryoftexas.com/, accessed 08/02/2017

[4] Benjamin Johnson, Revolution in Texas: How a Forgotten Rebellion and its Suppression turned Mexicans into Americans, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005); David Montejano, Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986); Julian Samora, Joe Bernal and Albert Peña, Gunpowder Justice: a Reassessment of the Texas Rangers, (South Bend: University of Notre Dame Press, 1979)

[5] Latino Law Students Association: University of Michigan, The J.T. Canales Award, https://sites.google.com/a/umich.edu/lawllsa/j-t-canales-award, accessed 08/02/2017. See also Benjamin Johnson, Revolution in Texas, (2005)

[6] http://politics.blog.mystatesman.com/2017/02/06/no-sanctuary-on-gov-abbotts-promise-that-texas-will-hammer-travis-county/

[7] Brandi Grissom and Robert Garrett, “I’ll put a bullet in your head’: Fistfight nearly erupts in final day,” Dallas Morning News, https://www.dallasnews.com/news/texas-legislature/2017/05/29/fistfight-nearly-erupts-final-day-caps-contentious-legislative-session,

[8] Geneva Sands, “if you entered the U.S. illegally, you should be very concerned,” ABC News, http://abcnews.go.com/Politics/ice-director-entered-us-illegally-concerned/story?id=48095531,

[9] http://www.npr.org/2017/07/20/537894936/ice-not-apologizing-for-aggressive-tactics