#OTD on August 22, 1919, a federal court indicted Francisco “Chico” Cano on several charges, the most serious was for the 1915 murder of former Texas Ranger Joe Sitter. A Customs Inspector at the time, Sitter had attempted to arrest Cano and died in a shootout in 1915.

Cano was born in Mexico in the 1880s. By the turn of the 20th century he ran a ranch with his brothers, Manuel, José, Antonio, and Robelardo near San Antonio del Bravo, Mexico, a community across the river from Candelaria, Texas. The brothers did well at cattle raising.

There had been a good deal of cattle rustling in the border region in the 1910s. Joe Sitter attributed these thefts to Chico Cano. Sitter owned a ranch near Valentine, over 100 miles away from Cano’s property in Mexico, but he still blamed Cano for every raid in the region.

In early 1913 without authority or authorization, Sitter set out to apprehend Cano. Two men, Customs Inspector Jack Howard and a cattleman named J. A. Harvis accompanied Sitter. They located Cano at the wake of a family friend near Marfa.

Cano surrendered to Sitter out of fear that the 3 man posse might harm the wake goers. Cano’s brothers made plans to rescue him. They likely feared that Cano would never make it to jail…law enforcement often killed suspects like Cano as they transported them to jail.

Brothers Robelardo and Manuel Cano rode out and ambushed Sitter and his posse. Sitter received a bullet wound to the head, but he survived. Harvis was shot in the leg and lived. Howard died several days later from a bullet wound to the stomach. Cano escaped.

After these events in the minds of White Americans and law enforcement, Cano was a bandit.

The press blew his exploits out of proportion, noting that he led “100 outlaws,” “150 bandoleros (outlaws),” or “bandits, 200 in number” in the Texas border region.

Cano supposedly had a second run in with Sitter when he and Ranger Eugene Hulen got word of Cano’s whereabouts after allegedly torturing a Cano confidant. After traveling to this location Sitter, Hulen, and others came under fire. The two died in the shooting.

Authorities found the men’s bodies badly disfigured, which amplified the hate for Cano. But there was never any proof that he had been there. Witnesses said the people who engaged Sitter were 120 feet away. Still, the 1919 federal indictment shows Cano was blamed for his death.

At about this same time, Cano became a leader in the Mexican Revolution, originally serving Venustiano Carranza and later forming his own militia. It’s hard to discern of he was a “bandit” or if he conducted raids as revolutionary. The Brite Ranch raid is a good example of this confusion.

In Dec 1917 a group of Mexicans raided the Brite Ranch, one of the key events that led to the Porvenir Massacre. The Rangers blamed Cano for the raid. But ranch owner Lucas Brite, doubted Cano’s involvement. Brite met with Cano who swore his innocence. Brite believed him.

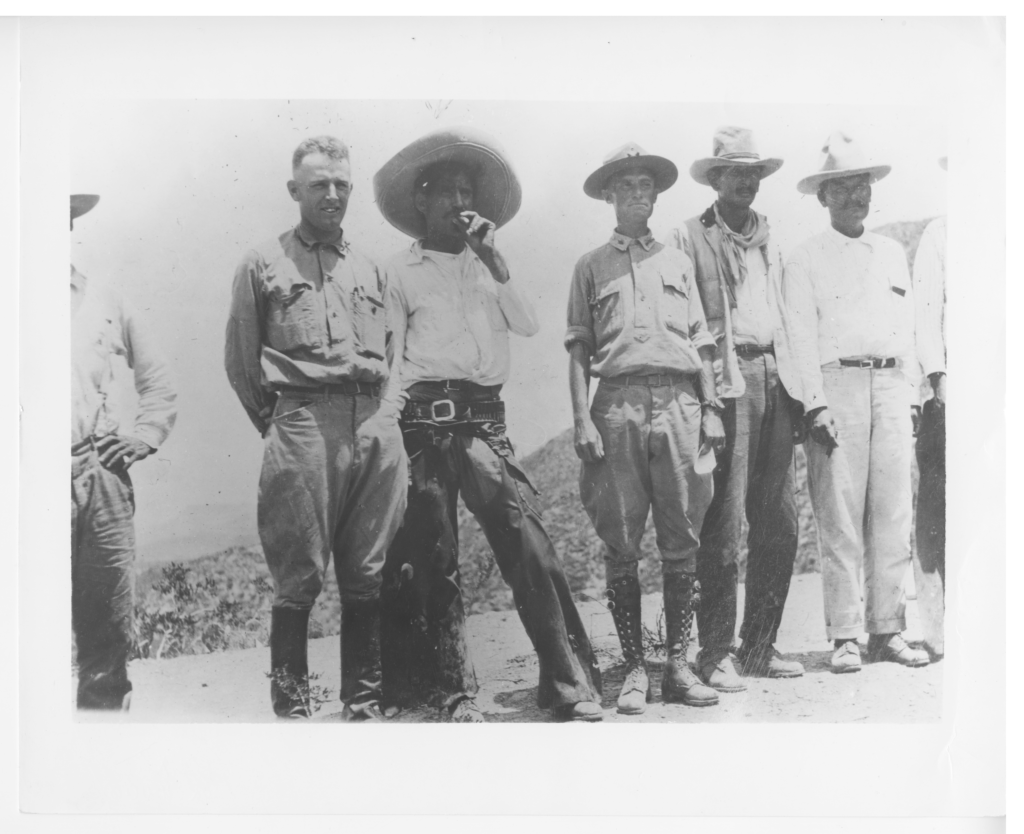

Chico Cano had many other strange encounters with authorities in Texas. The image below came from a 1919 meeting with US military officials. Cano, in the sombrero, is pictured with Major John Arthur Considine (left) Captain Leonard Matlack, and brothers José and Manuel Cano.

The meeting was probably designed to ease tensions between American military forces and those of Mexican revolutionaries. But the military also took it as an appropriate time to try to kill Cano. Matlack attempted to kill him shortly after this picture was taken.

Cano was shot 14 times over the course of his life, primarily by Texas Rangers, as they sought to end his exploits. But they would never capture or kill him. The 1919 indictment would linger, but Cano would never be tried. He outlived almost all of his opponents.

Cano only became a bandit when White law enforcement turned him into one, and even after Joe Sitter decided he was a bandit it remains unclear if he was an outlaw, revolutionary, or both. He was one of many Mexicans who became bandits because law enforcement named them so.

Chico Cano died at his ranch in 1943. When he was asked if he feared meeting his maker, Cano responded “My father was my maker. Poverty was my maker. Distrust was my maker. I have met them all my life.”

Major sources for this thread include @HistoryBrian’s Borders of Violence and Justice: https://uncpress.org/book/9781469670126/borders-of-violence-and-justice/.