#OTD in 1925 the Texas legislature passed SB 174, making illegal search and seizure by police a crime. Rep JT Canales had asked for more robust protections during the Canales Investigation. This is considered one of the Canales Reforms, even though he was not in office.

Senate Bill No. 174 had the lengthy title “An Act making the people secure in their persons, houses, papers and possessions from all unlawful and unreasonable seizures or searches.” It made it unlawful for law enforcement to acquire illegally obtained evidence.

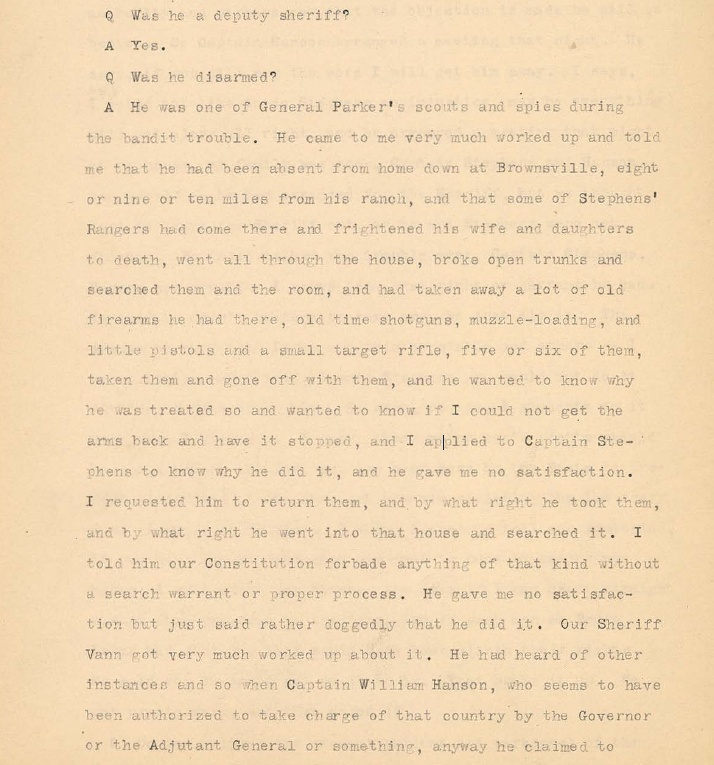

Although these rights are protected by the Fourth Amendment to the US Constitution, law enforcement frequently denied Texans of this right. Canales knew that the Rangers had violated the rights of Mexicans and Mexican Americans in this regard on a number of occasions. The Canales Investigation revealed many examples. Below Canales questions Judge James Wells about how Ranger George Sadler, who had possibly helped murder Florencio Garcia, had searched and disarmed Pedro Lerma, a deputy sheriff and prominent resident of Brownsville.

In addition to this, Rangers and other law enforcement agents acquired illegally gathered evidence and then used it to coerce confessions or as evidence in legal proceedings against Mexican-origin defendants. SB 174 attempted to curb these practices.

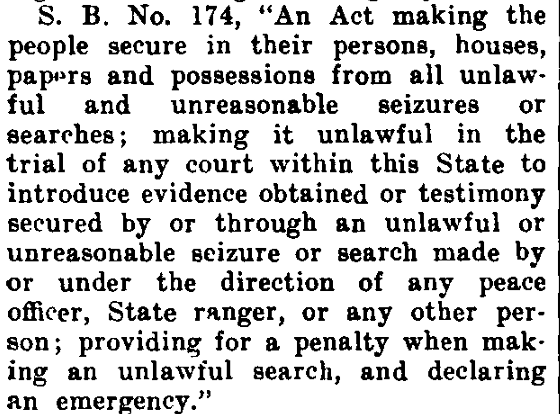

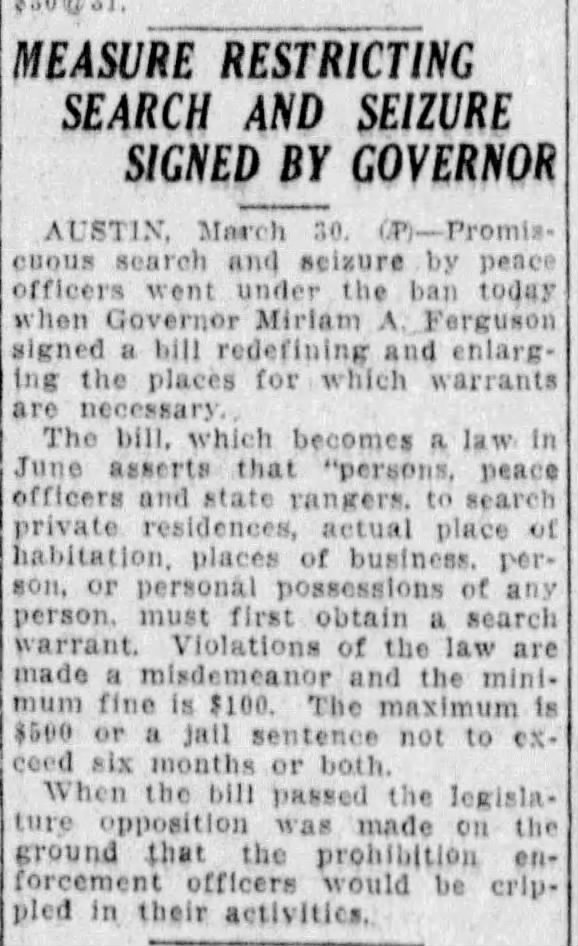

The law said that “any peace officer, state ranger, or any other person” who illegally obtained evidence could be charged with a misdemeanor punishable by a fine up to $500, 6 months in jail, or both. It also required officers to acquire a search warrant to instigate a search. All of these proscriptions were either already protected by Texas law or the US Constitution, but abused by the Rangers. It should be noted that law enforcement continued to violate these provisions. It took until the 1960s for the Supreme Court to rectify this situation.

The Court did so in Escobedo v. Illinois and Miranda v. Arizona, both of which involved Mexican American litigants. Escobedo (1964) asserted that a state must grant a person under interrogation access to an attorney, and once they ask for one questioning must end. Miranda (1966) asserted that during an interrogation a person not only had a right to counsel, they had to be informed of that right before questioning began. Without such a warning an individual might incriminate themselves, which would violate their Fifth Amendment rights.

SB 174 anticipated Escobedo and Miranda in some ways, although those case went much further than the legislation in Texas. Gov Miriam Ferguson signed the bill into law in late March 1925.

This thread is a part of the #OTD in Ranger history campaign that @Refusing2Forget is running this year. Follow this twitter handle or https://refusingtoforget.org/ranger-bicentennial-project/, and visit our website https://refusingtoforget.org to learn more.

The key source for this thread is @HistoryBrian’s https://uncpress.org/book/9781469670126/borders-of-violence-and-justice/

Refusing to Forget members are @ccarmonawriter @carmona2208 @acerift @soniahistoria

@BenjaminHJohns1 @LeahLochoa @MonicaMnzMtz and @Alacranita, another co-founder is @GonzalesT956

@emmpask @sdcroll @HistoryBrian @LorienTinuviel @hangryhistorian, @ddsanchez432! , Brent Campney, and Miguel Levario are other scholars working on this project.