#OTD on January 20, 1919, a white mob in Hillsboro, Texas, removed Bragg Williams from the county jail and burned him at the stake at the intersection of Elm and Covington streets on the southwest corner of the courthouse square.

Williams, an intellectually disabled Black laborer, had been found guilty and sentenced to death for the murder of Annie Wells and her son Curtis Wells outside of Hillsboro. This period was the height of mob violence in Texas, and the state’s governor William Hobby, feared that Williams would be lynched before the trial. So he sent Texas Rangers to move Williams to Dallas and protect him until his trial. But when Williams was convicted (by an all-white jury, of course, given Jim Crow curtailment of Black political rights), the Rangers abruptly and surprisingly left Hillsboro. The mob, incensed by the appeal that Williams’ attorneys filed, was able to break into the jail.

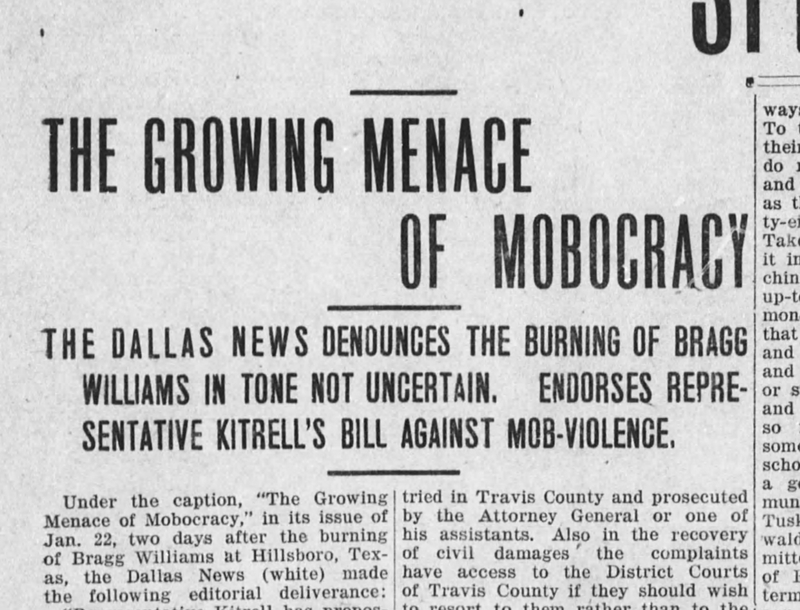

As was often the case, horrific photos of the torture were made and turned into postcards, images that we chose not to recirculate. The lynching provoked widespread condemnation, by the NAACP, the national press, and even many white Texas papers.

This lynching was the first one listed in An Appeal to the Conscience of the Civilized World, a 1920 publication by the NAACP that marked the organization’s embrace of an anti-lynching campaign. NAACP investigator John Shillady wrote to Governor Hobby requesting information about why the Rangers or other state officers were unwilling to protect Williams’ right to due process. Hobby did not reply. Rangers, historian Monica Muñoz Martínez writes, had “autonomy when they patrolled their regions. They made decisions about how and when to complete their investigations and also had the authority to extend their assignments.” They could have saved Williams.

Later, in the 1920s, Rangers would sometimes be dispatched to stop lynch mobs. State leaders increasingly opposed lynching, even as they supported the Jim Crow system that mob violence upheld, and used legal executions after unfair trials to secure the same result as lynching. The action of Rangers against lynch mobs is part of their record and is invoked by their defenders today. But they also knowingly left numerous victims to their horrific fates. This, too, is a part of their record.

Williams’ family fled Hill County. In 2019, Williams’ nieces, Crady Johnson and Tonya Carmel, read a newspaper article in the Fort Worth Weekly about the lynching on its centennial. They worked with the article’s author, historian E.R. Bills, to file an application for a historical marker for the lynching of their uncle. In 2022, the Hill County board unanimously gave permission for the marker’s placement.

“I think they needed justice, too,” said Tonya Johnson of the vote. “And maybe closure. It was a spiritual, humbling experience.” The historical marker application is currently pending.