Team member Sonia Hernandez describes forthcoming Texas State Historical Markers that recognize history of anti-Mexican violence in Texas.

The late writer, historian, and theorist, Gloria Anzaldúa once wrote as she reflected on the aftermath of the 1846 war between the United States and Mexico, that, “[Mexican Americans] were jerked out by the roots, truncated, disemboweled, dispossessed, and separated from [their] history.”[1] Indeed, it took decades of struggle of an entire community to include “[their] history” in the official record of Texas and the entire nation. It is 2016, and we have barely scratched the surface. There are efforts taking place today to transform our national curriculum into a more inclusive one; and, in some schools, Mexican American history and studies can actually be studied. Yet, the problem of who belongs in this country and who does not, recently fueled by nativist rhetoric has placed further obstacles and has begun to tear away at the right and access of communities to their own history. History is at the very core of what makes and enables communities to pass down their history to future generations. For many years, the Mexican-origin had to rely on oral histories passed down from one family member to another. The state of Texas, for years, failed to acknowledge its dark chapters and avoided any public acknowledgement of those individuals and organizations that sought to bring awareness to these issues.

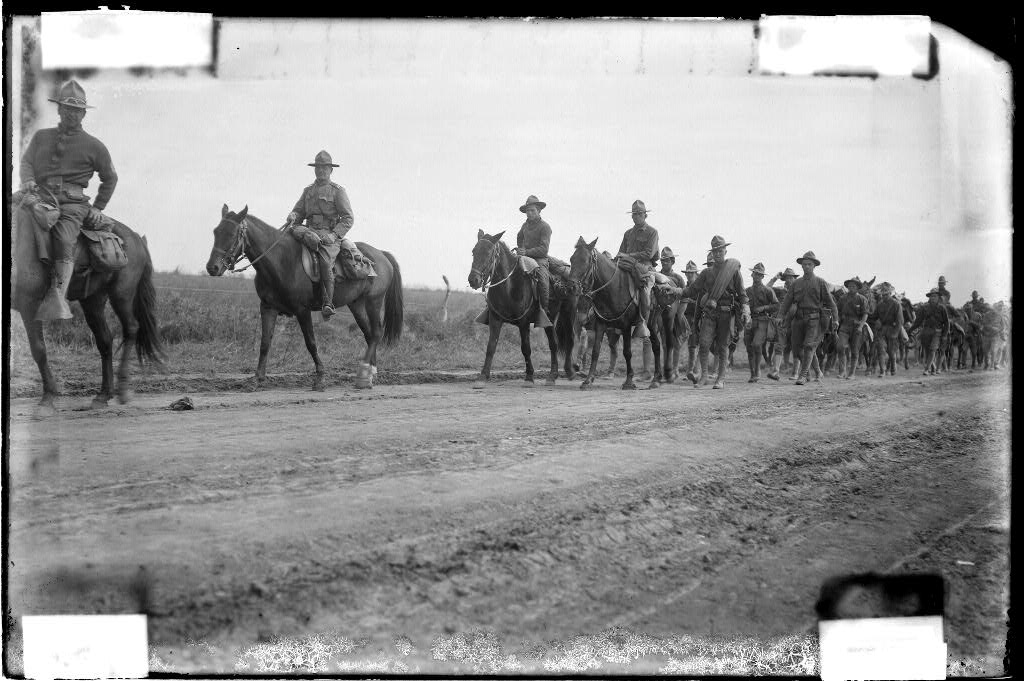

During the 1910 Mexican Revolution, particularly the 1915-1919 period, the Texas Mexican community along the border witnessed some of the most heinous acts of violence. Sanctioned by the state, members of the Texas Rangers, vigilantes, and local law enforcement killed innocent residents labeling them as bandits. The killing was so widespread that the reputableHarper’s Weekly published that during this period [noting the increase in violence in 1915] so many Mexicans were killed that it seemed as if “it were open gun season on Mexicans.” The violence was rampant and encouraged by state leaders that an investigation was called. In 1919, the only Mexican-origin Texas legislator, José Tomás “J.T.” Canales called for an investigation into the atrocities committed by the Rangers. This was the first time in the history of Texas that an official inquiry into the actions by this elite force took place. While the Investigation did not lead to any criminal punishment, it ushered public awareness of the atrocities, resulted in a decline in the number of Ranger agents, and more importantly, paved the road for a long civil rights struggle. As we approach the centennial of the 1919 Canales Investigation, the Texas Historical Commission (THC) has approved three key historical markers that are part of this long ignored dark chapter in our state and nation’s history. It is precisely this effort to bring such events to the forefront of Texas public and official history that the project Refusing to Forget has embarked upon.

Not only is this project concerned with acknowledging the sites and moments of violence, but it is interested in this history in order to present a balanced, nuanced narrative–not a simple victim-driven narrative that fails to address community response and activism that emerged as a result. The three historical markers approved by the THC include the “1915 Matanza/Killing” (Cameron County), “The Porvenir Massacre, 1918,” (Presidio County), and “Jovita Idar,” (Webb County). The area spanning from the towns of Mercedes and San Benito, in Cameron County, served as the site of numerous killings or matanza. The term references a surge of anti-Mexican mob violence in the area. The community of Cameron County, including Mercedes, San Benito, Los Indios, among others, will now find some closure with a historical marker that will mark the site of such violence for deep reflection on this period. Further, a historical marker “Porvenir Massacre” honors the victims of this atrocity that occurred in 1918. In January 28, 1918, Company B of the Texas Rangers surrounded the residents of Porvenir and divided fifteen able bodied men from the women, children, and elderly men. With the help of the 8th regiment of the U. S. Cavalry, the Rangers searched the homes for weapons. Captain James Monroe Fox then dismissed the U.S. soldiers. Without conducting interviews, the Rangers proceeded to execute the fifteen men ranging in age from 16-64 years old. The Massacre was one of the worst episodes of violence in our country. State recognition of this atrocity had been anxiously awaited by family members of the victims who, for years, had collected artifacts, documents, and histories of this dark chapter in their community. Some of the widows of the murdered proceeded to submit lawsuits in the wake of the massacre.

The Refusing to Forget team worked closely with the local historical commission such as Webb County. Chair, Jeanette Hatcher, was thrilled to see an application for “Jovita Idar.” The commission had just approved a marker for the “Primer Congreso Mexicanista, 1911,” which brought much needed attention to the widespread problem of lynching of people of color. Ethnic Mexicans were repeatedly lynched, often times snatched from local jails stripping people from their right to a trial in court. Jovita Idar, as well as members of the Idar family, participated in the Congreso to raise awareness of the violence and to promote anti-lynching, anti-violence legislation as well as improve the socio-economic conditions of Mexican Americans in south Texas. These markers are crucial to documenting the active participation of Mexican Americans in their quest for justice and equality.

While historical markers are but one example of state acknowledgment of the atrocities committed against the Mexican origin community, the approval of these three markers—almost 100 years after the 1919 Canales Investigation of the Texas Rangers, signal a new era and is a step forward in transforming our state and nation’s history.

[1] Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, third edition (Aunt Lute Books, 1999), 29-30.